The Coming of HMS Queen Elizabeth: Preparing for Its Initial Deployment

The coming of the HMS Queen Elizabeth to the UK combat force is a trigger for significant defense transformation. Most of the analysis of the new carrier really focuses on the platform and what is necessary to get that platform operational but that is far too narrow an approach.

The carrier is a centerpiece, trigger or magnet for broader UK defense transformation within a unique historical context, namely, the broader strategic shift to dealing with higher end operations and the coming of Brexit.

At the heart of the focus of getting the HMS Carrier strike group to sea is its projected maiden deployment in 2021. This is a significant challenge and the focus of attention of the Royal Navy and its industrial partners and a major element of my discussions while at Portsmouth.

During my visit to Portsmouth, I had the opportunity to talk with two key Royal Naval officers working hard to prepare the carrier for its first operational deployment. Captain Allan Wilson and Captain Mark Blackmore in Navy Command provided an overview on the way ahead with the carrier task force as well as a very insightful look at the challenge of working several intersecting programs coming together in the future maritime task force.

Captain Blackmore is the Senior Responsible Officer for the Queen Elizabeth carrier and functions as Admiral Brand’s right hand man in delivering the carrier. They are not responsible for F-35, which is the function of air command. But with three new aircraft coming onboard the Queen Elizabeth, they are working with the integration of the other aircraft as well and closely with joint helicopter command.

For example, the integration of the aircraft to fly on the carrier is part of the challenge as well, and includes three new aircraft, the F-35, Commando Merlin, and the Crow’s Nest.

And the carrier is shaping a shift from the current concepts of operations for the Royal Navy to a new one as well. Currently, the key focus is upon targeted deployment built around a single ship to an area of interest. With the carrier, a maritime task force is being built which will go together to an area of interest.

This change alone requires significant change as the shipyards will now have to manage the return of the task force and the maintenance cycle task-force driven as opposed to a cycle of dealing with single ships combing back from a targeted deployment.

The current goal is to have the HMS Queen Elizabeth deployed on its maiden deployment in 2021.

As Captain Blackmore highlighted the way ahead: “We accepted the ship last December and she will go off for the next two years to do fixed wing trials. We will do DT one and two this Autumn, DT three next Autumn, then OT with the goal of getting and IOC for carrier strike in December 2020 and then about four months later, we plan to deploy CSG-21. My focus is clearly on this end point, namely the first deployment to the Arabian Gulf or wherever it is finally decided to do the initial deployment.

“Prince of Wales comes on about two years astern to Queen Elizabeth and she will be seen off of the US Eastern Seaboard in 202 to do the rolling landing trials. We have a new landing aide called a Bedford array which is fitted to Prince of Wales which allows us to exploit the full enveloped of rolling landing and gives the pilot visual cues which enhance his capability to come back to the ship with more fuel and weapons as needed, The Queen Elizabeth will then be fitted with the new system.”

A key element for the carrier is clearly its integration with the F-35 for which the DTs will occur this fall off of the Virginia coast. The declaration of full operational capability for the carrier is correlated with the operation of the first 24 F-35Bs, which will occur by 2023.

The new carrier embraces both the carrier strike and amphibious assault roles. As Captain Blackmore put it: “Carrier naval power projection is both an organization and a capability and it captures both the literal maneuver amphibious element and also the carrier strike element.”

The US is playing a key role in the UK working towards 2021. One aspect is clearly working with the USMC on F-35B and jointly training at MCAS Beaufort.

The Marines will be evident on the ship as well with their operating from the ship during DT trials as well.

A second aspect which came up in the discussion concerning the workup for the infrastructure was the participation of the US military sealift command in Portsmouth, a subject covered in a separate interview.

The third aspect is working with the US Navy on various aspects of preparation and training for carrier operations. In 2012, an agreement was signed between the US and the UK providing a broad agreement on collaboration and joint training which has been evident throughout the workup of the Queen Elizabeth. During my visit, I met with Lt. Commander Neil Twigg, who has just come from the USS George W. Bush we he operated as a Super Hornet pilot. He is the resident fast jet expert on the staff at Navy command.

As Captain Blackmore put it: “We have been involved with the US Navy with regard to to the training of personnel and the concepts, the processes and the organizations that need to come together to make a carrier a carrier. As a US Admiral noted, “This is not a pickup game. This is not something you just step onboard and just do.”

Working with the US has been a central piece of the activity to bring on line the Queen Elizabeth. The new carrier is designed differently from a US large deck carrier and will operate differently from the US carriers, and part of the transition is sorting out a way ahead for the UK concept of carrier operations. And that is clearly a work in progress.

But it is rooted in the design of the ship to operate F-35Bs and helicopter assault forces in varying combinations dependent on the mission. It is also rooted in building out new ships and missiles to operate with the ship, and to be able to operate in the distributed operational battlespace being shaped by the US and other allied forces as well.

The new carrier both supports and interacts with all of these trends.

How will the carrier both contribute to and learn from these broader macro allied military transformation dynamics?

A core commitment of the UK government is to have a 100% available carrier strike capability. This means that the maintenance and workup cycles for the two carriers need to be synchronized to ensure that this can be the case. It is a significant challenge in that workforce, training, airpowers systems and maintenance of the carrier need to be synchronized and not just with the carrier but with the other elements of the maritime task force.

Given that the focus of the Royal Navy in the past few years has been very different, namely focused on deployment of single ships or maritime combinations built around a single non-carrier ship, shifting to the concepts of operations for a carrier strike group is very different.

Much of Captain Allan Wilson’s presentation and focus during the discussion was precisely on how to meet the challenge of the coming of a maritime task force. The Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force and MoD more generally have being adapting their organizational structure to ensure that the kind of integration, which a maritime task force enabled, by an F-35B will be successfully developed and delivered. This is no easy task.

And Captain Wilson also noted that building out such a capability was a significant challenge but it must be met with a proper training regime to ensure a high level of readiness of the carrier maritime task force.

Captain Wilson noted: “We are redesigning force generation.

“In the past, and currently as we do with our amphibious task force, we deploy ships perhaps in a task force configuration and then they reach full operational readiness during the operation.

“When we come back to the UK, we do not maintain the task force at a high level of readiness. With the carrier task force approach, we are shifting our training focus to ensure that the task force is at a high state of readiness when it first deploys.”

“We are focused on shifting the training to an incremental training pathways of the task force capability to ensure higher

“We bring the individual elements of the task force together to work together after they have done their initial training. We then integrate the jets with the task force in both synthetic and live training and get them up to certification before they go anywhere.

“We will certify the task force to high level of readiness prior to deployment and will deploy within that period of time. And we plan to keep that task force together for a four-year cycle, which will require synchronization across the key elements of the task force in terms of maintenance, training and manning.

“That is not how we have done it in the past. The deployment has always been the headmark. We have surged units in and out of the task force. And we have worked the pieces individually.”

Captain Wilson underscored the challenge of aligning the work up of the carrier and its evolving task force approaches with the aircraft coming onboard the aircraft for its maiden deployment.

In this context, we discussed the Crimson Flag exercise to be held at RAF Marham in 2020.

Captain Wilson posed a key question: “How do you bring the other combat elements into a blended synthetic-live combat training environment to work with F-35?”

He provided an answer: “We have an exercise at RAF Marham scheduled for October 2020 called Crimson Flag. USMC jets will be at RAF Marham joining the UK jets in the exercise. We are looking at what rotary wing assets will be available as well for this exercise. We bring ships crew into the exercise to work the exercise and to focus on combat capability generated from the deck of HMS Queen Elizabeth.”

In short, the new carrier is a key part of the overall dynamics of change within UK defense. And the senior Royal Navy team is clearly approaching this from an integrated approach looking at the cross cutting changes throughout the navy and air force as well the ground assault forces as well. It is clearly a very dynamic and innovative process, one which will see significant challenges along the way as a core new capability is crafted for the United Kingdom.

Note: There are several aspects of the new UK carrier of interest to broader considerations of the evolution of the airbase, including manpower requirements, weapons handling, C2 capabilities and flexible command posts, electric power generation, building the infrastructure to handle the requirements of a data rich aircraft which is the F-35B, and building unique F-35 specific capabilities, such as the ski jump and the unique rolling landing capabilities.

Also, see the following:

http://www.indiastrategic.in/topstories3766_A_Tale_of_Three_Carriers.htm

https://sldinfo.com/2017/02/merlins-in-the-future-of-the-queen-elizabeth-carrier/

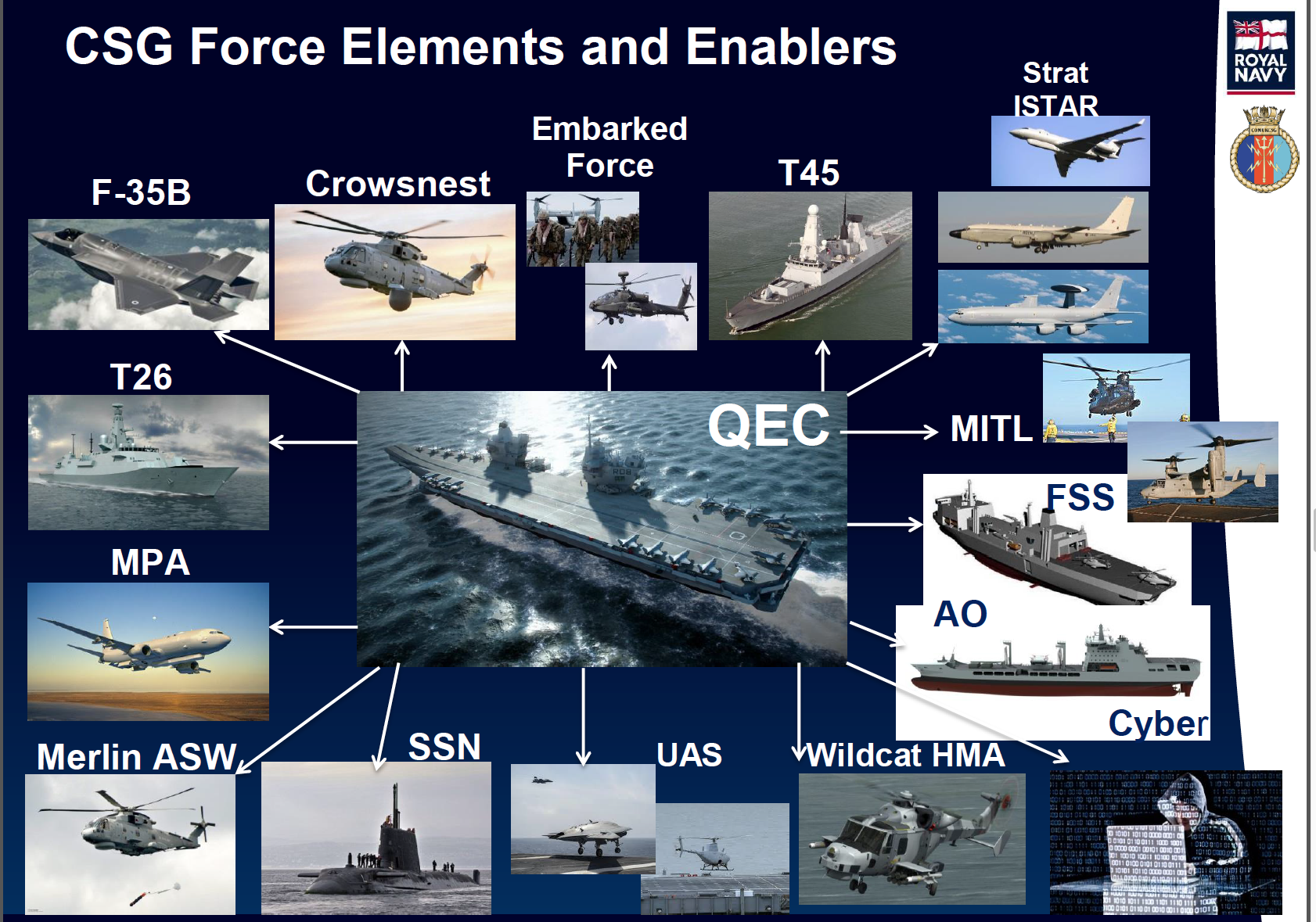

The featured graphic was taken from Captain Nick Walker’s presentation at the Williams Foundation seminar in 2016.