The Return of Geography in the Defense of Australia

As Australia thinks through its options for enhanced capabilities to defend the nation in the changing strategic context of the Indo-Pacific region, Australian geography may well be returning in a way not seen since the days of World War II.

During World War II, Japan directly attacked Australia in order to try to ensure that it would not function as a launch point against Japanese extended territorial defense. Japan had significantly expanded its territory and control over the Pacific and its islands; it was threatened by the United States and its ability to operate in the Pacific from various island bases and certainly the notion that Australia could become the unsinkable aircraft carrier for the allies was a key concern for Japan.

Although dramatically attacking Darwin with the same naval task force which had earlier attacked Pearl Harbor, the Japanese ultimately failed in its efforts to negate Australia and its role as the key ally of the United States in defeating the Empire of Japan.

The Battle of the Coral Sea was clearly a key turning point in this phase of the War.

With the Chinese pushing out from the mainland and shaping a phased island strategy, their ability to project power out into the Pacific raises again the question of the role of Australian territory, notably Western Australia and the Northern territories in the defense of Australia.

An enhanced role for these territories in extended deterrence is a distinct possibility for the Australian Defence going forward.

Some in Australia would see this as a Fortress Australia policy, but it really something quite different.

It about the ADF can operate from Western Australia and the Northern Territories much more flexibly and do so as if the territory operated a chessboard across which forces could be moved in a crisis.

There first of all is the question of Australian forces and the ability to do so.

The RAAF will certainly look at agile basing and enhanced capabilities to operate from a variety of airstrips and mobile bases.

The Navy already operates their submarine force from Western Australia and as the new build submarines are added to the force, might next flexibility be considered in how to operate the force, somewhat similar to how Australia operated in World War II.

This leaves the key question of the role of the Army.

There is a beginning of change within the Australian Army as new strike capabilities in support of the maritime force and new active defense capabilities are being built.

But might not the Army have an even more significant role as the Aussies look to leverage F-35 2.0 and provide longer range strike and active defense capabilities for a power projection force designed to go much deeper into the Indo-Pacific region to defend Australian interests?

In addition, there is the consideration of key allies, notably Japan and the United States.

For the United States, a major challenge is to generate a much more mobile and flexible force able to operate with an alternative to large fixed bases.

Cooperation with Australia could provide flexible basing in a crisis but only if the United States can really learn how to show up for relatively short periods of time but operated a sustainable force.

And to do this without permanent basing of a sort not relevant to the 21st century and the crisis management challenges on the horizon.

For the Japanese, as they add new military capabilities, such as new ships, new submarines, new aircraft and new strike systems, they clearly will be looking to move capabilities on a short-term basis outside of the limited perimeter of their island chain.

A good starting point for change could well be for Japan and the United States to learn how to operate their F-35s from the sustainment facilities the Aussies are building for their own F-35s.

This would mean that if desired by the Australians in a crisis, the United States, Japanese or other F-35 partners could fly to bases in Australia, bases with significant active defenses or ability to operate from mobile bases, and be maintained by Australian sovereign capability.

The F-35 inherently can do this; but it would require a revolution in sustainment thinking on the US and allied side to achieve what is inherent in the aircraft itself as a combat system.

It is a case study of a broader set of changes which could interweave with the changing role which territory will play in 21st century extended deterrence in the Indo-Pacific region.

And such a return of geography, raises some fundamental questions as well for the ADF, notably for the Army which has thought of itself largely in out of Australia expeditionary terms. Now it might play a much more significant role in terms of the defense of Australia in terms of its national territory, notably in Western Australia and the Northern Territories.

For the United States to be an effective partner in such a change would require significant alterations in how the US power projection forces operate as well. It would require building on those areas where common platforms are yielding potential for common sustainment and weaponization solutions, but generated from the Aussie side.

It is not about turning Australia into a Fed Ex set of terminals for the American forces; it is about an agile, flexible engagement force which could show up for 90 days in a crisis and support common policies and interests.

And the weaving in of the Japanese will be a challenge as well both on the Australian and Japanese as well for the Americans who have to shed their superpower mindset and think in terms of regional crisis management and their contributions and role in a tailored set of crisis solutions.

To reset how to think about geography in relationship to the new platforms and technologies is a major challenge not only in a rethink of Australian defense but for Australia’s closest allies as well.

This means as well that infrastructure and its defense becomes a core strategic challenge for both Australia and its closest allies.

It is high time to recognize that Chinese efforts to buy commercial ports and infrastructure really is about ensuring that the obvious trajectory of change for Australia and its closest allies is something which the Chinese wish to obviate without firing a shote.

It takes a strategic vision to constrain the Chinese; and we need to generate such an approach.

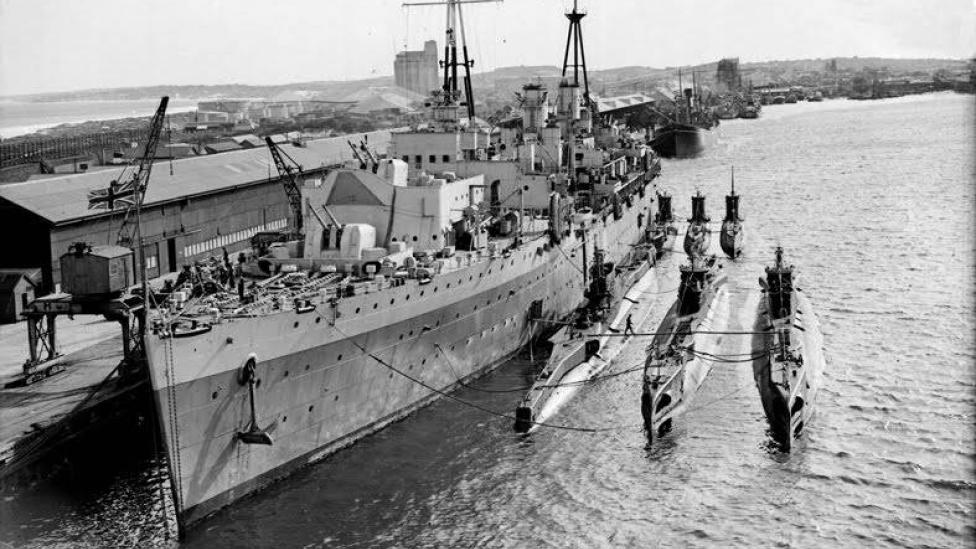

The featured photo shows the Fremantle submarine base in World War II.

When it was fully active the base saw 160 Dutch, American and British submarines pass through the Australian harbor.

The base was tied in with the Indian Ocean campaign of 1942–45.

Military historians looking at the strategy in the South East Asian Theatre look upon the command of the Commander Submarines, South West Pacific (COMSUBSOWESPAC), and the facility of the Fremantle base as integral to successes in 1943 onwards.