The Signing Of The Aachen Franco-German Treaty: Towards More or Less European Defense Integration?

Recently, the leaders of France and Germany have signed a new treaty in the city of Aachen***.

Aachen or Aix-la-Chapelle in French is the city of the birth of Charlemagne, Aachen.

It has been the theater of five treaties: the first one was signed in 1668 and put an end to the war of Devolution between France and Spain; the second, in 1748, put an end to the succession war in Austria; the third, concluded in 1816, established the borders between the Netherlands and Prussia; the fourth – the so-called Congrès d’Aix-la-Chapelle – followed in 1818 the Vienna Treaty; and finally this month, on January 22nd, 2019, France and Germany signed a Treaty “on Franco-German Cooperation and Integration”.

It is not clear yet whether this latter Treaty will enter History the same way its predecessors did, but it shares the same aspiration to counter instability and divisions in Europe.

Reaching out towards the next level in European integration by energizing the old Paris-Berlin engine has been President Macron’s agenda in the past two years, as his speech at the Sorbonne University in 2017 and his initial (and very brief) appointment of Sylvie Goulard – a European MP known for her support for strong Franco-German ties – as Minister of defense, clearly indicated.

That agenda has been crumbling under the weight of domestic tensions on both sides of the border with Chancelor Angela Merckel losing her hold on the coalition in power in Germany and a growing grassroot opposition in France illustrated by the Yellow Vests movement.

The question therefore is what might be the true impact of such a treaty in the current environment and can its long-term goal of more integration be achieved?

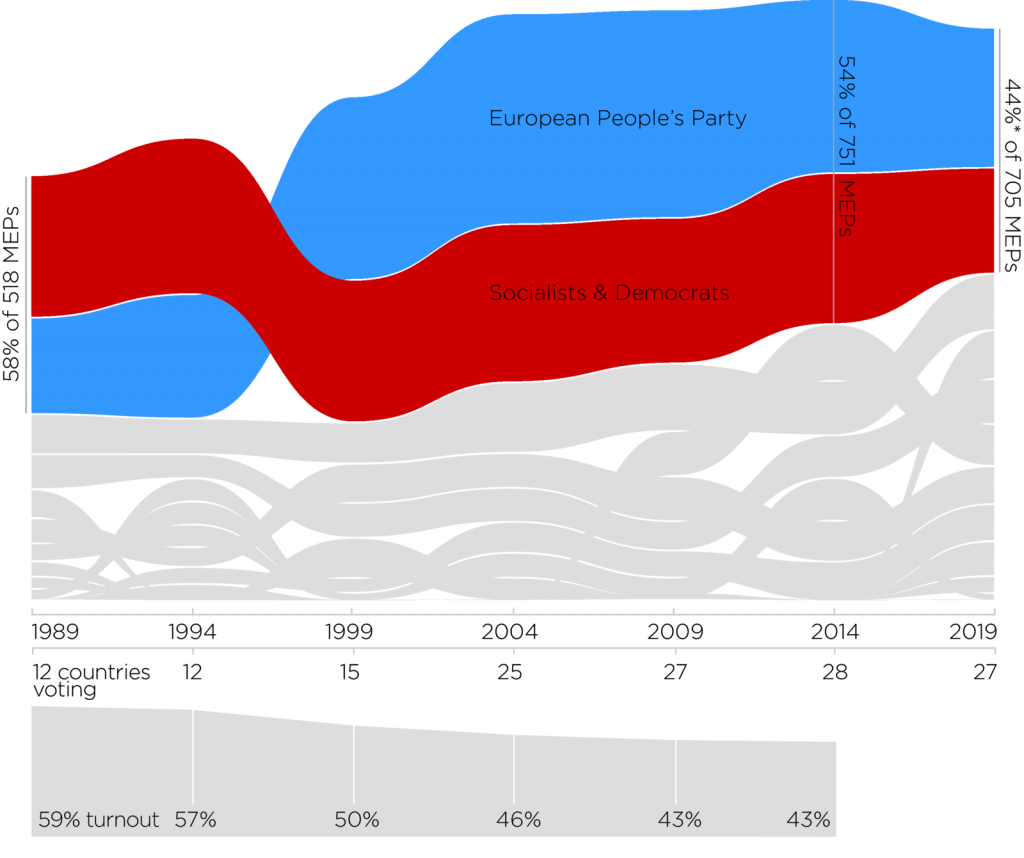

In the short term, the prospect of the upcoming European elections tends to blur any assessment and color the debate. Traditionally, antagonistic voices are being heard loud and clear in an unprecedented manner as the extreme right and the extreme left are taking advantage of both the tearing apart of the classic political parties and system and the new information age.

Current projections forecast a 35% support for the CDU and 23.5% (22.5% if the Yellow Vests manage to have a list) for LREM (President Macron’s party), while the French (ex-)National Front ranks second.

Graph credit: https://www.politico.eu/article/european-election-2019-in-pieces-where-voters-disagree/

Such a trend would not play in favor of more integration in Europe – quite the opposite –while the Aachen Treaty is already being challenged by some critics (such as Assas law professor Olivier Gohin) for being unconstitutional and not respecting national sovereignty.

Criticism is being directed across the spectrum of opinion from the relatively low-key (accusation of more symbolism than real content) to the absurd (the de facto secession of Alsace and Lorraine to Germany).

In the longer run though, three aspects of the 2019 Aachen Treaty – which intends to be an updated version of the 1963 Elysée Treaty of friendship signed between then President Charles de Gaulle and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer – could however bear fruit and reinforce European collective defense in a broader and constructive sense, if not integration.

Joint (and concrete) Projects

The first, involves joint projects.

“Jointly invest to fill capability gaps, therefore enhancing the European Union and the North Atlantic Alliance”(Article 4 §2): the spirit of the 60’s with the franco-german consortium Transall (or “Transport Allianz “) and C160 legacy seems to be back, as there is a common will on both sides to work out their respective cultural differences.

Defining a joint approach towards arms export is part of solving past and current conundrums.

Working towards joint tanks, artillery and a Future Combat Air System currently benefits from a strong bilateral political support, vision and financial commitment, which has already redefined the industrial defense landscape in Europe. Spain has shown interest in the SCAF, while Poland has recently stated that participating to the franco-german tank was on the table.

Similarly, the promotion of innovation on both side of the border with concrete steps in tune with the XXIth Century digital economy works in synergy with the determination to fight the risk of lagging behind game-changing technologies. The replacement of the “old” (the Fessenheim nuclear power plant) with the “new” (innovation centers and IA platforms, as described in Article 21) is a good illustration of such a shift.

Enhanced Military Co-operation

“Further reinforce the cooperation between the two armed forces (…) in order to operate joint deployments ” (Article 4 § 3) and to establish “a joint unit meant for stabilization operations in third party countries” (Article 6).

Past initiatives such as the Franco-German Brigade have been challenged by significantly different post–WWII operational traditions.

French forces have kept their expeditionary legacy while the German forces have been reluctant to go beyond peacekeeping missions.

There is also the question of the disconnect between fundamentally different political system authorizing military intervention. In France, the order may come from the President while in Germany the Bundestag has to approve it.

This clearly affects the nature and timing of operations.

This is changing in the past few years with a growing German military presence in Niger for instance as part of the war against terrorism in Sahel.

An example of the change is stronger cooperation to tighten a partnership between Europe and Africa (Article 7).

And such cooperation is clearly part of a broader effort to enhance security in Europe as a whole, with migration being such a divisive issue on the old Continent as well.

Enhanced Common Strategic Culture

“Establishing a common culture” (Article 4 § 3) is a leit-motif for the current German and French leaderships in order to unite Europe. The hope is for a riddle effect to occur with the current knitting of bilateral partnerships by both the German and the French sides. There is actually a re-centering of Berlin in Europe, if one observes the recent signing of cooperation agreements between Germany and Poland, and Germany and the Netherlands for instance.

Many Europeans are however critical of what is perceived as a “Paris-Berlin axis” and propose other types of European models and alliances (e.g. the New Hanseatic League or the « Italo-Polish axis » advocated by Italian leader Matteo Salvini).

However, the Aachen treaty, which promotes bilinguism on the franco-german border (Article 5) and joint franco-german officials both in executive and legislative frameworks, could be a tool to both formalize the existence and development of a youth genuinely European at heart, as well as to be an embryo for a joint European stance in multilateral bodies, such as the United Nations (Article 8).

Conclusion

There may be still a long way to go to make true John F. Kennedy’s dream to “look forward to a Europe united and strong – speaking with a common voice – acting with a common will – a world power capable of meeting world problems as a full and equal partner” (A New Social Order, June 24, 1963, The Paulskirche, Frankfurt, Germany).

But one has to focus on the concrete initiatives as stepping stones behind the big symbolic gestures, especially the ones which go beyond the bilateral franco-german friendship, such as Air Policing missions (France is the second largest contributor with seven NATO deployments over Estonia, Lithuania and Poland since 2007) or the development of a common strategic culture in the Baltic region with Germany, but also Denmark, Estonia and Finland in the framework of the European Intervention Initiative (EI2) launched last June.

At the end of the day, the only glue fostering a common European defense is a common threat perception, and that, in the Baltic area, is unfortunately not lacking.

The featured photo comes from the French President’s first visit to Berlin.

*** A version of this article was published on Breaking Defense on January 31, 2019.