Re-Setting Australian Defense: Lessons from the Battle of Britain

On 13 August 1940, the Luftwaffe, Hitler’s air arm, set out to destroy the Royal Air Force’s ability to defend the airspace over and around Great Britain. That day 79 years ago—code-named Adlertag (‘Eagle day’)—was the beginning of the main phase of the first campaign of strategic consequence fought entirely in the air. When the dust settled at the end of October, the RAF had emerged the victor of the ‘Battle of Britain’, ensuring that German invasion plans would be put on hold indefinitely.

I started thinking about the lessons from 1940 and subsequent air campaigns after reviewingHugh White’s How to defend Australia here in The Strategist. Hugh essentially sees Australia as being in a similar position to Britain in 1940, relying on the combined efforts of a large strike fighter force and submarines to thwart designs a major power might have on Australian territory. I’ll look at the air component of his vision in this post.

To extract the appropriate lessons from history, we need to understand which factors are enduring and which were specific to the time. And we need to understand what actually happened, rather than a romanticised version. The commonly held view of the campaign today is largely based on the words of Winston Churchill, who characteristically seized the moment in 1940 with a bold rhetorical flourish. His construct regarding the RAF’s Fighter Command—‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few’—memorably invokes an image of a small and outnumbered but supremely gallant band of airmen fighting off the Nazi hordes.

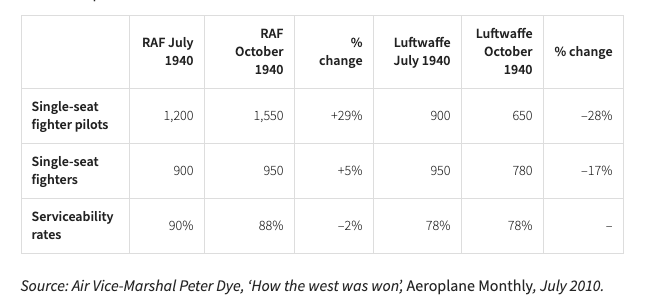

But while it’s true that Fighter Command came under enormous stress and suffered terrible losses, that picture is far from complete. In fact, despite loss rates that modern air forces couldn’t sustain for any length of time, the RAF had more fighters and more pilots at the end of the air campaign than when it started. The numbers in the table below are telling—at no stage from Adlertag onward was the RAF outnumbered in either fighter or pilot numbers. In addition, an efficient maintenance and repair capability ensured that RAF fighters were consistently maintained at higher levels of availability—an important force multiplier.

We can add a few more statistics to complete the picture. The RAF’s fighters flew more than 20,000 sorties in August, compared with 13,000 by Luftwaffe fighters. The differential was even greater in September, when the battle reached its peak: in the week of 23 September the RAF flew almost 5,000 fighter sorties to the Luftwaffe’s 1,000. And the numbers of aircraft arriving from the factories were startlingly different: Britain produced 4,283 new fighters in 1940, compared with 1,870 from German plants.

Given how much numbers matter in air combat, having more aircraft, more pilots and higher rates of availability placed the RAF in the box seat to prevail—despite losing more than 50% of its aircraft and 20% of its pilots in both August and September. The other factor it had going for it was geography; it was operating closer to home, so aircraft range and endurance were less constraining than for the Luftwaffe. As well, RAF pilots who bailed out were likely to be back with their squadrons in a day or two, while surviving Luftwaffe pilots ended up in POW camps.

That brings us to Hugh White’s ‘Battle of Australia’ scenario in which 200 frontline aircraft form a bulwark against a hostile power. The lessons from 1940 mostly apply, with the exception of the rapid production of replacement aircraft, given that the lag time for a new strike fighter is well over a year.

Numbers still matter, and in a defensive posture geography would be on our side. Taking steps to ensure we could generate the number of sorties required would maximise the chances of success. Here are the enablers that need to be in place to make best use of an expanded fast-jet force (some of which Hugh includes in his book):

- an adequate number of hardened forward bases to reduce transit time to operating areas

- reliable supplies of fuel and other consumables to those bases

- more trained pilots than aircraft (I doubt we could do that now with half the aircraft numbers)

- efficient and effective forward maintenance facilities to reduce turnaround times between sorties

- efficient second-line maintenance and repair to return aircraft to service

- tanker aircraft to keep aircraft airborne for longer

- an efficient rescue capability for ejected pilots (from both sides).

If we could do that, it would make the projection of air power against Australia a formidable task and would go a long way to ensuring the nation’s security against overt armed attack. (Though, as Peter Hunter points out in his recent ASPI report, that should be only part of a national strategy.)

‘Never in the field of human conflict have so many owed so much to a combination of an efficient training pipeline, good field logistics and effective just-in-time mobilisation of the industrial sector’ doesn’t have the same stirring ring as Churchill’s famous line—but it would have been more accurate.

Andrew Davies is a senior fellow at ASPI and lectures on defence acquisition at the Australian National University. Image courtesy of the Royal Air Force Museum.

This article was published by ASPI on August 13, 2019.

Also, see our analysis of the lessons learned from the Dunkirk retreat, see the following: