Is the B-21 Bomber a Viable Option for Allies?

Australia needs to consider its options for projecting greater military power in an age where we can’t assume that we’ll get assistance from the US whenever and wherever we need it.

In my recent Strategist series on projecting power with the F-35, I looked at options to overcome the jet’s inherent range limitations so it can project further into the vast expanses of the Indo-Pacific. It can be done to some extent, but all scenarios require large-scale investment in enabling capabilities—ranging from air-to-air tankers to off-shore bases—as well as capabilities such as ground-based air defence to protect it.

I’d planned to examine the full range of strike options before unveiling the punchline—namely, the B-21 Raider strategic bomber. But since ASPI analyst Catherine McGregor has reported that two former air force chiefs think we need strategic bombers, I’ll cut to the chase and look at whether that’s a viable option.

As context let’s review some history. Australia has operated long-range bombers in the past—the ‘G for George’ Lancaster bomber occupies pride of place in the Australian War Memorial. In the European theatre in World War II, the RAAF flew Halifax, Wellington and Lancaster bombers, and it also operated long-range strike aircraft including B-24 Liberators in the Pacific.

In the post-war period, Australia operated the Canberra bomber. The Canberra’s range was limited and it was replaced with the F-111C, which had a combat radius of over 2,000 kilometres as well as the ability to be refuelled mid-air. That put Jakarta within its range, and while it’s debatable whether Australia would have ever considered bombing our neighbour’s capital, the capability itself certainly got the Indonesians’ attention. And that’s the point of high-end strike capabilities—they act as a deterrent and shape others’ thinking even if they’re never used.

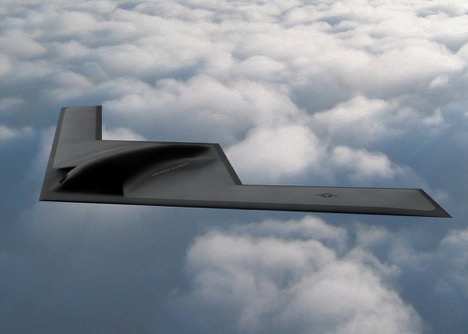

So we’ve recognised the need for long-range strike aircraft before. Today there aren’t many options for a strategic bomber. Unless we acquire used US B-52, B-1 or B-2 bombers (all of which would come with a serious downside), the only option is the B-21 being developed by the US Air Force (Unmanned systems are potentially another option, but there’s nothing out there right now.) There’s not a lot of information available about the B-21, but the USAF’s intent seems to be that it will be at least as capable as the B-2.

That suggests it will have an unrefuelled combat radius of around 5,000 kilometres. As shown in the figure below, that would allow it to operate from deep within Australia (I’ve used Alice Springs to illustrate the point) and still cover the entire archipelago to our northwest, the South China Sea, our South Pacific neighbours, and the gap between Guam and Papua New Guinea.

Because of its inherent range, the B-21 wouldn’t require air-to-air refuellers. Being based well inland, it wouldn’t be exposed to the same extent to the threats that our northern bases or offshore airbases are faced with. A strike platform like the B-21 would still require sophisticated enablers to find and precisely target an adversary in that huge combat radius. Those come at a substantial cost.

The B-21 could deliver a broad range of effects. A strike package of four aircraft could likely carry around 40–50 long-range maritime strike weapons, which would inflict unacceptable losses on any maritime or amphibious task force. If the target was the adversary’s forward operating bases, a first wave of aircraft could use long-range stand-off weapons to destroy their air defences (including aircraft on the ground), with each bomber in a follow-up wave delivering around 80 precision-guided JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munition) bombs, or around 200 small-diameter bombs.

Moreover, the bombers could return the next day, unlike a submarine which could need a month to return to the fight after going home to reload once it had launched its handful of strike missiles. No other system could deliver a comparable weight of fire. It would certainly get the attention and shape the military planning of any power that wanted to operate in that huge circle.

The B-21 could also be used tactically to deliver close air support to Australian and allied troops on the ground, as US bombers have done in the Middle East. A single B-21 could carry about as much ordnance as a squadron of F-35s but with greater range and persistence over the target and fewer enablers.

But it wouldn’t be able do everything.

A B-21 won’t perform anti-submarine warfare in the same way as the ADF currently does it with a combination of ships, submarines and aircraft. But it could do it in a different way—for example, by striking enemy submarines in port or by air-dropping smart sea mines off those havens or in key choke points.

Based on public information, it’s possible that Australia could get aircraft into service in the second half of the 2020s. So it couldn’t happen overnight, but it’s certainly faster than even the most optimistic future submarine schedule.

Of course, that great capability comes at a great cost.

The USAF is aiming at a unit cost of US$564 million in 2016 dollars. That’s if it can get the 100 aircraft it wants and escape the death spiral of other programs like the B-2 and F-22, which cut production numbers to reduce program costs. That drove up unit costs, which in turn forced cuts to projected unit numbers. So we would probably be looking at a cost of around A$1 billion per aircraft.

It’s hard to know how many we’d need for a viable capability. The RAAF acquired 24 F-111Cs, followed by 15 F-111Gs, but at retirement there were only 13 left in service. The USAF is operating a fleet of 20 B-2s. Let’s assume the sweet spot is around 12 to 20 aircraft. Since total program costs are usually around 1.5 to 2 times the cost of the aircraft themselves, we’d be looking at around $20–40 billion. That’s a lot of money, but less than the cost of the future submarine program.

The real challenge is always affording the annual cash flow without gutting the defence budget. Unlike the future submarine program, which is drawn out over nearly 40 years, the bulk of the spending to acquire the B-21 would likely be compressed into five or six years, requiring around $5–6 billion per year. That’s over half of Defence’s capital equipment budget. And it’s more than the entire local shipbuilding program when it is up and running (which has been declared untouchable).

It’s hard to see Defence being able to afford that without a massive cash injection from the government. But if the government is serious about addressing our worsening strategic environment, the B-21 would be an investment that made both friends and potential adversaries sit up and take notice.

Marcus Hellyer is ASPI’s senior analyst for defence economics and capability.

Image: Northrop Grumman.

This article was published by ASPI on November 6, 2019.

In a September 18, 2019 piece by Stephen Kuper published in Defence Connect, the possibility of allied participation in the B-21 program was highlighted,

The precedent already established by the collaboration between Defence Science and Technology and Boeing on the development of the “loyal wingman” concept provides avenues for Australia to partner with defence industry primes and global allies to develop a long-range, unmanned, low observable strike platform with a payload capacity similar to, or indeed greater than, the approximately 15-tonne payload of the retired F-111.

The US has developed increasingly capable long-range, low observable unmanned platforms, including the Lockheed Martin RQ-170 Sentinel; the highly secretive Northrop Grumman RQ-180 high-altitude, long-endurance, low observable intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft; and Northrop Grumman’s X-47 series of carrier-based, low observable strike platform.

Meanwhile, BAE Systems has successfully developed and tested the Taranis unmanned platform at the Woomera Test Range as a proof of concept for future collaboration and development – each of these individual platforms provide a unique opportunity for Australia to collaborate with a global industry prime and a global ally to fill a critical capability gap for each of the respective forces.

Such a capability would also enjoy extensive export opportunities with key allies like the US and UK, who could operate the platform as a cost-effective replacement for larger bombers like the ageing B-52H Stratofortress, B-1 Lancer and B-2 Spirit, and complement the in-development B-21 Raider long-range strategic bomber – even drawing on a common airframe, avionics and engine suite to enhance interoperability while reducing supply chain challenges.

For the UK, the co-development and participation in such a system will fulfil a unique role – complementing the air-to-air and air-to-ground strike capabilities of the Eurofighter Typhoon and F-35 Joint Strike Fighter as a low observable, long-range, heavy strike aircraft to counter the rapidly modernising bomber fleet of an increasingly resurgent and assertive Russia.

Similarly, Australia needs a credible, long-range strike option capable of replacing the lost capability of the F-111 to penetrate increasingly advanced and complex integrated air defence networks and anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems rapidly developing in the Indo-Pacific region.

The introduction of such a system could also support the development and eventual modernisation of the US B-21, which is being developed in response to the increasing air defence capabilities of both Russia and China, particularly the widespread introduction of the S-300 and S-400 integrated air and missile defence systems.

And then in a follow up article by Kuper published on November 6, 2019, the possibility was discussed further.

For Australia, the retirement of the F-111 platform, combined with the the limited availability of the Navy’s Collins Class submarines, has left the nation at a strategic and tactical disadvantage – limiting the nation’s ability to successfully intercept and prosecute major strategic strikes against air, land and sea targets that threatened the nation or its interests in the sea-air gap, as defined in the 1986 Dibb review.

The growing debate about Australia’s tactical and strategic force structures, combined with the underlying paradigm shift away from a purely ‘defence force’ towards a more traditional, ‘armed force’ style of defence strategy has, in recent days prompted retired Air Marshal Leo Davies and his immediate predecessor, Air Marshal (Ret’d) Geoff Brown to call for greater Australian long-range strike capabilities.

While the acquisition of the Super Hornets in the mid-to-late 2000s and the acquisition of the fifth-generation F-35 Joint Strike Fighter to fulfil a niche, low-observable limited strike role have both served as a partial stop-gap for that lost capability, the nation has not successfully replaced the capability gap left by the F-111.

Additionally, there were recent announcements about Australia’s pursuit of an advanced remotely piloted aircraft system (RPAS) as part of the AIR 7003 program and the advent of the Boeing Airpower Teaming System – designed by Boeing in collaboration with Defence Science and Technology – to enhance the air combat and strike capabilities of the Royal Australian Air Force.

The acquisition of the Reaper-based RPAS, MQ-4C Triton, and development of the fighter-like Boeing Airpower Teaming System all serve niche roles as part of a broader and increasingly complex air dominance, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance and close-air support strike mix – neglecting the critical long-range strike capabilities once filled by the F-111.

Australia is not the only nation facing a growing shortfall in its long-range aerial strike capabilities as the Cold War-era fleet of American strategic bombers, namely the B-1 Lancer, the B-52 Stratofortress and B-2 Spirit all entering the realm of obsolescence despite years of modernisation and upgrades – further compounding the survivability of these platforms is the advent of advanced Russian and Chinese air defence systems.

In response, the US Air Force and industry partner Northrop Grumman have initiated the B-21 Raider program to replace the ageing strategic bomber fleet of the US Air Force with a focus on responding to the rise of these advanced integrated air defence systems.

Like it’s immediate predecessor, the B-21 is designed to be a low-observable, penetrating strategic bomber capable of a prompt conventional or nuclear global response.

Cost overruns present opportunities for Australia

In recent decades, even the US has had to face significant cuts to its military expenditure across research and development, acquisition, sustainment and modernisation, and the new B-21 program is no exception, as the US Air Force has steadily increased the planned number of airframes to be acquired, the cost has equally risen, placing increased pressure on existing and future acquisition programs.

The US Air Force currently has plans to acquire 100 B-21s to operate in conjunction with a fleet of 75 B-52s that will be modernised. However, as the Air Force surges towards an ambitious plan to field 386 squadrons, up 75 from its current strength, will translate to an increased fleet of B-21 aircraft, with additional strategic experts in the US calling for a larger fleet of between 50 and 75 additional Raiders.

This growing number of new, costly platforms has drawn the attention of the head of the US Air Force’s Global Strike Command, General Timothy Ray, who has made thinly veiled comments about America’s allies, raising questions about the potential for allied participation in the B-21 Raider program to ease the economic and strategic burden on the US.

“Only the United States flies or builds bombers among its allies and partners. The last foreign squadron retired in 1984,” he said.

This concern has been identified by Ben Packham of The Australian, referencing the US Secretary of Commerce, Wilbur Ross, who said the US would “look favourably” on an Australian request to participate in America’s long-range strike aircraft program – namely the B-21 Raider.

Secretary Ross reportedly told Packham, “We have no intention of vacating our military or our geopolitical position but we would be delighted to sell Australia more aircraft if that’s what suits your Department of Defence.”

The precedent already established by the collaboration between Defence Science and Technology and Boeing on the development of the “loyal wingman” concept provides avenues for Australia to partner with defence industry primes and global allies to develop a long-range, unmanned, low-observable strike platform with a payload capacity similar to, or indeed greater than, the approximately 15-tonne payload of the retired F-111.

The US has developed increasingly capable long-range, low observable unmanned platforms, including the Lockheed Martin RQ-170 Sentinel; the highly secretive Northrop Grumman RQ-180 high-altitude, long-endurance, low observable intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft; and Northrop Grumman’s X-47 series of carrier-based, low observable strike platform.

Meanwhile, BAE Systems has successfully developed and tested the Taranis unmanned platform at the Woomera Test Range as a proof of concept for future collaboration and development – each of these individual platforms provide a unique opportunity for Australia to collaborate with a global industry prime and a global ally to fill a critical capability gap for each of the respective forces.

Such a capability would also enjoy extensive export opportunities with key allies like the US and UK, who could operate the platform as a cost-effective replacement for larger bombers like the ageing B-52H Stratofortress, B-1 Lancer and B-2 Spirit, and complement the in-development B-21 Raider long-range strategic bomber – even drawing on a common airframe, avionics and engine suite to enhance interoperability while reducing supply chain challenges.

For the UK, the co-development and participation in such a system will fulfil a unique role – complementing the air-to-air and air-to-ground strike capabilities of the Eurofighter Typhoon and F-35 Joint Strike Fighter as a low-observable, long-range, heavy strike aircraft to counter the rapidly modernising bomber fleet of an increasingly resurgent and assertive Russia.

Similarly, Australia needs a credible, long-range strike option capable of replacing the lost capability of the F-111 to penetrate increasingly advanced and complex integrated air defence networks and anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems rapidly developing in the Indo-Pacific region.

The introduction of such a system could also support the development and eventual modernisation of the US B-21, which is being developed in response to the increasing air defence capabilities of both Russia and China, particularly the widespread introduction of the S-300 and S-400 integrated air and missile defence systems.

Deputy Opposition Leader and defence spokesman Richard Marles reinforced the need for a more robust Australian response, telling The Australian: “[The government would] ignore air marshals Davies and Brown at its peril. Not only do we need the right strike force, it is essential that our defence forces are fully resourced to properly support that strike capability. We must have the most capable and strategic defence force possible.”

Former RAAF Air Chiefs Call for Investments in Long Range Strike Capabilities

In an article published in The Australian on November 5, 2019 by Catherine McGregor, Air Marshal (Retired) Geoff Brown and Air Marshal (Retired) Leo Davies focused on the need for long range strike capabilities for the RAAF. Both by the way came from the F-111 program in their careers.

Australia must urgently review its air and maritime strike capabilities in order to meet the threat posed by a rising China and a possible retreat by the US from our region, two former air force chiefs have warned.

Retired Air Marshal Leo Davies and his predecessor Air Marshal Geoff Brown have warned that two decades of insurgency-style conflict in the Middle East have left the Australian Defence Force poorly equipped to meet the new era of great-power conflict between the US and China.

The former chiefs have added their voices to growing disquiet within the strategic defence community over Australia’s capability. Both say Australia may need to invest in a strategic bomber and drones to enhance the air force’s range and impact, along with land-based ballistic missiles.

Air Marshal Davies, who was chief of the Royal Australian Air Force for four years up to July, has called for a “reset” of Australia’s defence posture. He has argued that our existing naval and air assets may not be able to defend the country’s sea lines of communication — the primary maritime routes used by military and trade vessels — or fight a hostile foreign power.

“The force that we used to carry out nation-building in the Middle East cannot defend our sea lines of communication or prevent the lodgment of hostile power in the Indo-Pacific region,’’ Air Marshal Davies told The Australian. “But without a reset we will keep developing it against an outdated set of strategic circumstances.”

Air Marshal Brown, who led the RAAF from 2011 to 2015, called for a major increase in air power, saying that, as the strategic outlook changed, the air force, not the army, was likely to be the service of “first resort’’.

“As an advanced technological nation about to get deeply into space we should be playing to our strengths,’’ he told The Australian. “Investment in air crew and technology is actually incredibly efficient for a small nation with an educated population.”

The former air chiefs’ rare contributions to the debate come at a time of strategic upheaval, with the increasingly assertive role played by China forcing defence planners to rethink the country’s force posture.

Anti-Access/Area Denial Capability for Australia

In an article by Malcolm Davis which was published by ASPI on November 25, 2019, the author builds on an article published by Alan Dupont which was published earlier in The Australian with regard to the need for long range strike.

Dupont emphasises the need to reinvest in the US–Australia alliance under more adverse strategic circumstances, but how we achieve that is an important question. Leaving the US to sail into harm’s way, perhaps during a crisis over Taiwan in the next decade, because we lack the means to project power rapidly alongside its forces won’t strengthen the alliance. A better answer is to raise our strategic currency in Washington by acquiring new capability to directly share the defence burden quickly, precisely and decisively.

Ignoring the issue of the strike gap risks our not having the means to support the US at some future critical hour. This is not to say that the ADF as it’s currently configured, or with the future force structure in mind, is incapable of contributing to a coalition operation. Both the Hobart-class air warfare destroyers and the Hunter-class future frigates can ‘plug into’ US taskforces, and the Attack-class future submarines will also be able to make a valuable contribution. However, the first of the submarines won’t appear until 2034 at the earliest, and we won’t have the first frigate until the late 2020s. Because our current naval surface-warfare capabilities don’t have a credible long-range land-strike or anti-surface-warfare system, they would have to go well within the range of China’s missiles in its anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) envelope to deliver a limited strike.

A more fundamental issue is whether events will have decided the outcome of the Indo-Pacific strategic contest well before the ADF’s future force is in place. Related questions include how advances in unmanned systems and hypersonics will transform the operational environment and whether legacy platforms will be able to keep up.

Hellyer’s analyses of options for projecting power (here and here) demonstrate that in terms of the RAAF’s strike and air combat capability, the current and planned forces, while technologically advanced, lack the range, persistence and payload to meet an increasing challenge to the region from a rising China. Having access to forward air bases will help, but it will also increase costs because our forces will then be located well within China’s expanding A2/AD envelope.

Debating the case for long-range strike implies building an A2/AD capability that emphasises projecting power forward rather than continuing a narrow denial strategy that surrenders the initiative to our adversaries. They can deploy their forces out of harm’s way and choose the time and place to strike at our critical defence facilities in the north unmolested. We are then left trying to defend our territory and airspace, or our expeditionary naval forces, against their cruise- and ballistic-missile capabilities. Our defences get swamped, ships are sunk and our bases are destroyed.

Long-range strike gives us the basis of a credible A2/AD capability for the ADF that raises the cost and operational complexity for any major-power adversary, contributes towards strengthened non-nuclear deterrence, and reinforces the US–Australia strategic alliance.

Certainly, there are no quick, cheap fixes for the strike gap. All the options—B-21 Raider, land-based ballistic missiles and long-range unmanned combat aerial vehicles—have cost, developmental and political implications that we can’t ignore. But accepting the strike gap means also accepting that we are less able to support our essential ally in a much more contested environment against a peer adversary that is clearly intent on directly challenging both the US’s and our security interests. Strengthening the alliance in a clear, decisive and highly visible way would signal to Washington that we will not be a free rider in a much more dangerous future.

See, the Williams Foundation Report on Australia and the question of long range strike as part of the deterrent strategy:

Also, see the following: