Peter Fleming’s Brazilian Adventure

In 1951, during my first year at Queen’s College, Taunton, then a boarding school for boys (it is now coeducational) we had a marvelous history teacher, H. J. Channon, better known to everyone as “Dapper. ”

H. J. Channon was the epitome of “Mr. Chips” of the famous novella by James Hilton, about a beloved teacher, Mr. Chipping, at a fictional minor boarding school for boys. The book was published in 1934, first in the U.S. by Little Brown and Company, and then in the U.K. by Hodder & Stoughton.

“Dapper” Channon was subsequently the subject of TV broadcast from the school in 1958 by Edmond Andrews in his popular “This is Your Life” program.

“Dapper” Channon had been a formidable cricket player and coach. He recounted tales of the legendary amateur cricket all-rounder, W. G. Grace (1848-1915) who had dominated the sport. “Dapper” had entered Queen’s College in 1900, then matriculated at London University, and returned at the invitation of the head master to be an assistant teacher. During the First World War he commanded with the rank of major the Queen’s College Cadet Battalion. “Dapper” Channon retired in 1949 but he continued to teach pupils in their first year.

I was held back a year, so l had “Dapper” as a teacher for two years. The extra year was fortuitous for me. I was a year younger than the average age of my class in my first year and my position was 18 very near the bottom. In my second year when my age was more like the rest of the class l came in as number two.

“Dapper” Channon wrote a weekly column on local history for the regional newspaper, the “Somerset County Herald.” He read his forthcoming column to us each Wednesday (correcting the long page proofs as he went along.) I loved these unconventional classes. He certainly inspired in me the desire also to write newspaper columns.

My first letter to the editor l published as “a young radical” in the “Somerset County Herald” in 1956. I made a copy in my diary. I called for the resignation of the prime minister, Anthony Eden. His disastrous British led military intervention in the Suez Canal I wrote had provided cover for the coincident invasion by the Soviets of Hungary to brutally crush the democratic uprising there. I was fifteen at the time.

“Dapper” Channon was fascinated by the fate of Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett, his son Jack, and his son’s friend, another young Englishman, Raleigh Rimmel, both in their early twenties, who had all disappeared in the jungles of the central Brazilian plateau in 1925.

Colonel Fawcett, then 57 years of age, was looking for a “Lost World.” “It is certain” he wrote “that amazing ruins of ancient cites – ruins incomparably older than those of Egypt – exist in the interior of Mato Grosso.” “Dapper” recounted the tale of the mysterious disappearance of these intrepid explorers often and with gusto. As indeed had the international press in the 1930s after Fawcett’s disappearance.

Interest in Colonel Fawcett has been revived more recently by James Gray’s “The Lost City of Z,” and the successful 2016 film of the same title directed by David Grann. And recent deforestation in the Amazon has indeed revealed the presence of major earthworks and the routes of ancient passageways.

Robert Peter Fleming (1907-1971) the author of “Brazilian Adventure” (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1934), was the older brother of Ian Fleming (1908-1964), the creator of James Bond, whose first Bond spy novel, “Casino Royal” was published in 1952.

The Flemings came from a wealthy family of Merchant Bankers (Richard Fleming & Co). I never quite understood what merchant bankers did. Some fellow students at Cambridge in the early 1960s said they were going to work the city of London after graduation as “merchant bankers.” Fleming’s father, Major Valentine Fleming, who had been a Member of Parliament and a barrister, was killed on the western front in 1917.

Peter Fleming was educated at Eton College and Christ Church, Oxford University, where he was the editor of “Isis” the major student publication and acted in amateur theatricals. He was a member of the Bullingdon Club (as later would be David Cameron and Boris Johnson). He was sent in 1929 by his mother to Wall Street where he arrived in New York City just in time for the collapse of the financial markets. Giving up on a career in banking he returned to London where he became the literary editor of “The Spectator.” He took a four month leave to serve as honorary secretary to a trade mission to China.

It was an entry in the “agony” column of “The Times” that led him to Brazil and in search of Colonel Fawcett.

Fleming wrote that he preferred the agony column to the “great stage of fools to which the editorial pages of ‘The Times’ so faithfully hold up a mirror.” The agony column on the other hand was “a world of romance, across which sundered lovers are forever hurrying to familiar rendezvous..a world of faded and rather desperate gentility..a world of sudden and heroic sacrifices”.

It was in the agony column that Fleming saw an advertisement: “Exploring and sporting expedition, leaving England June, to explore rivers Central Brazil, if possible, ascertain fate of Colonel Fawcett; abundance game, big and small; exceptional fishing, ROOM TWO, MORE GUNS; highest references expected and given. – Write Box X, The Times, E.C.4.”

Peter Fleming applied. He was 24.

Before long he was committed to the expedition in the capacity of a “special correspondent” for “The Times” to “a venture..for which Conrad designed the scenery.”

Actually, l know the feeling well. At 19 towards the end of my first term at Cambridge l saw an invitation pinned on the notice board in the junior combination room at St. John’s College. It offered a place on a trip to the Soviet Union over the following Easter vacation. I applied and was accepted. I at least got to Moscow in Easter 1961 just in time to see Stalin in his mausoleum on Red Square (he was removed later that year) and to spend time in Berlin on the way by train to Moscow and back before the Berlin Wall went up.

Not quite an invitation to the jungles of central Brazil to be sure, but pretty close in terms of would-be exoticism.

Fleming’s account of his Brazilian Adventure is that of an anti-hero. It deliberately debunks the heroic adventure travel narratives.

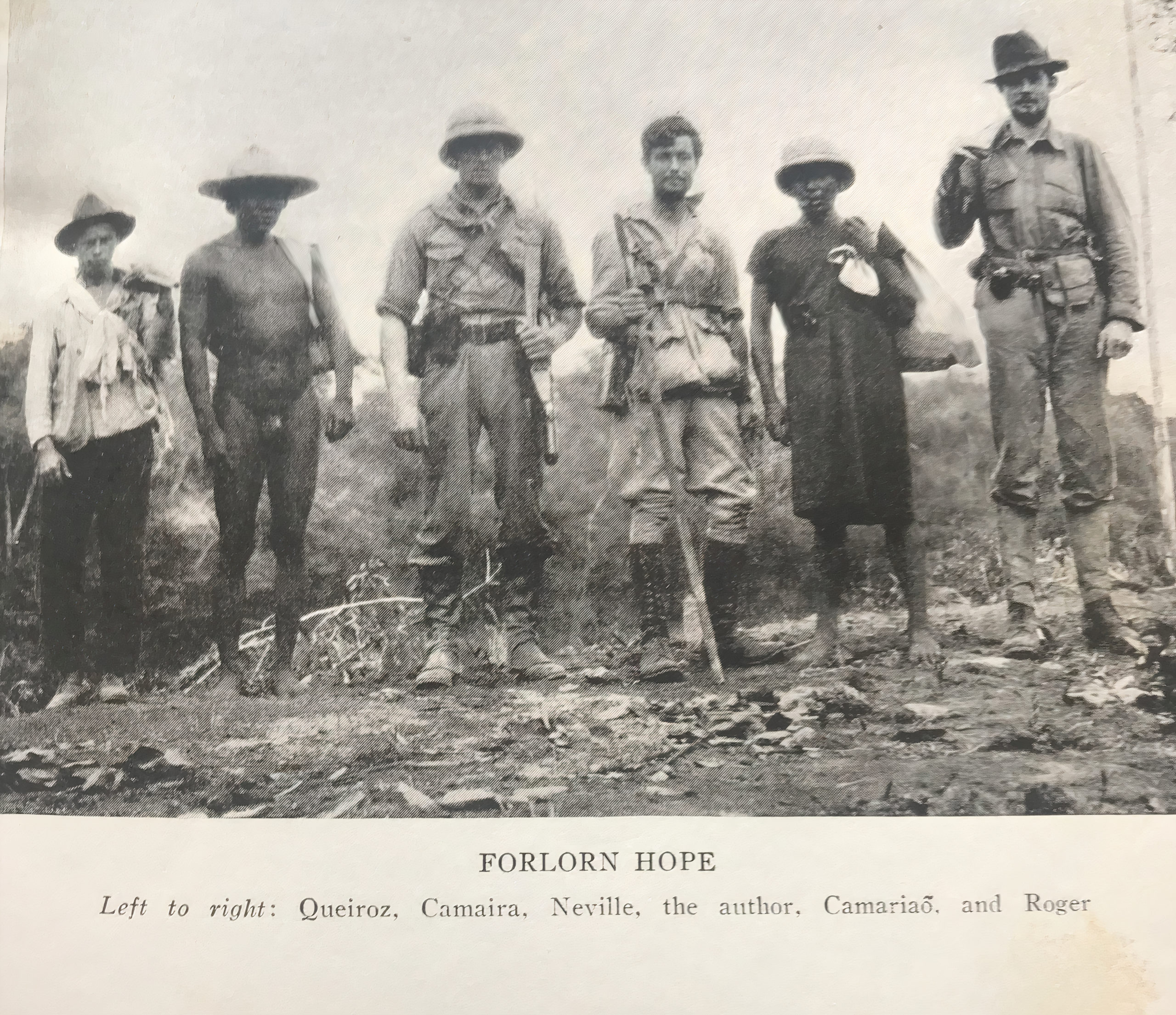

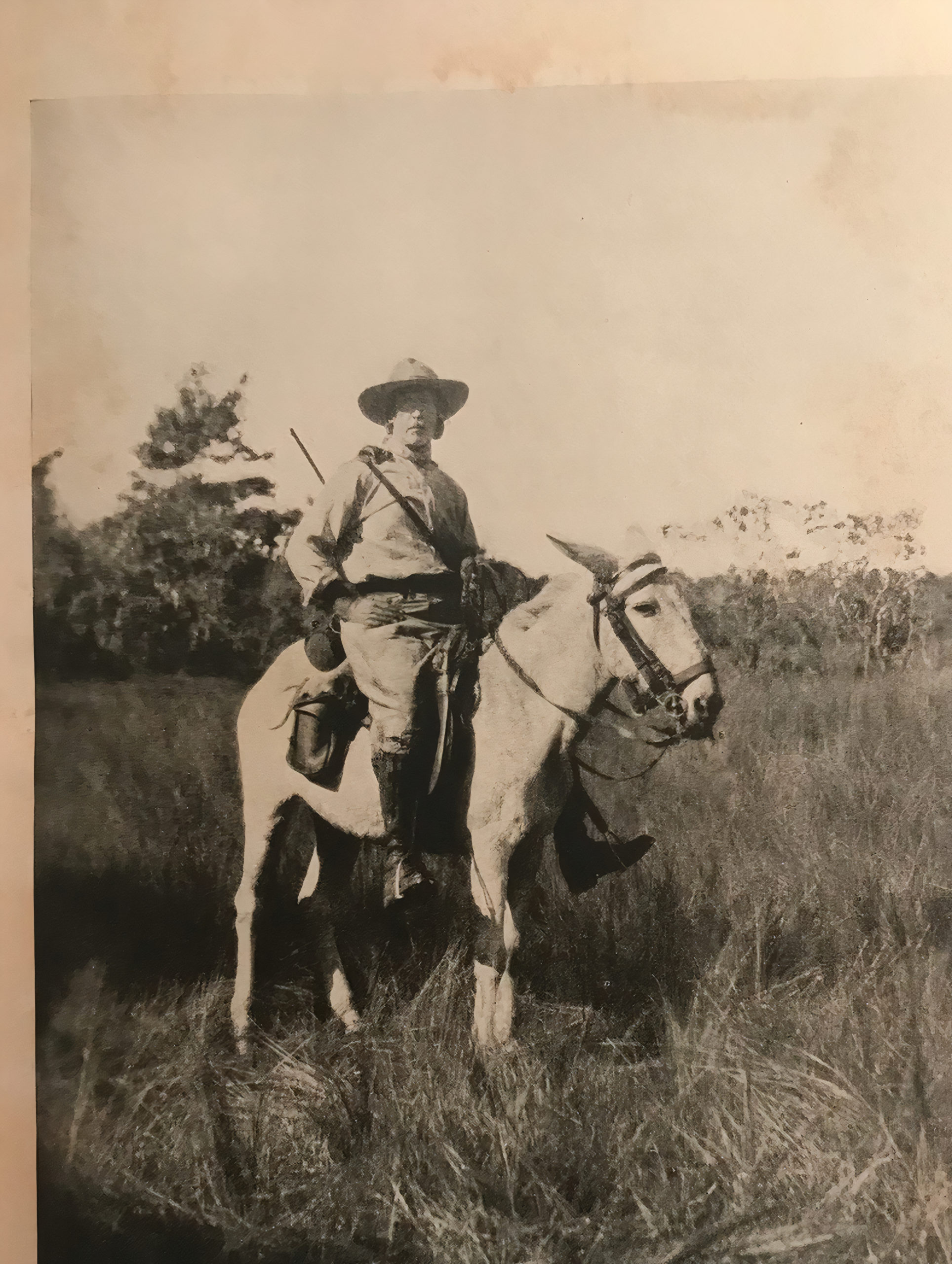

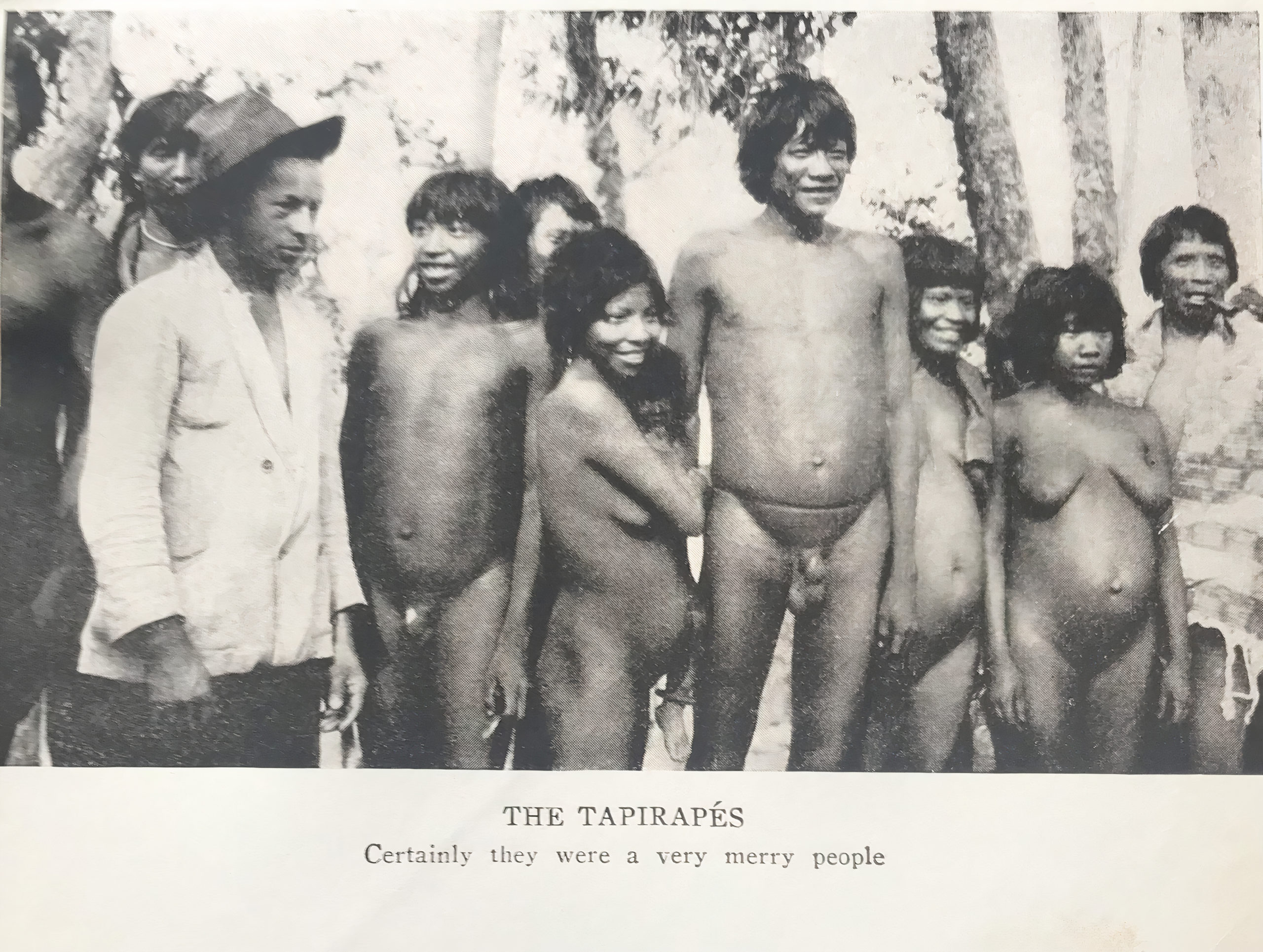

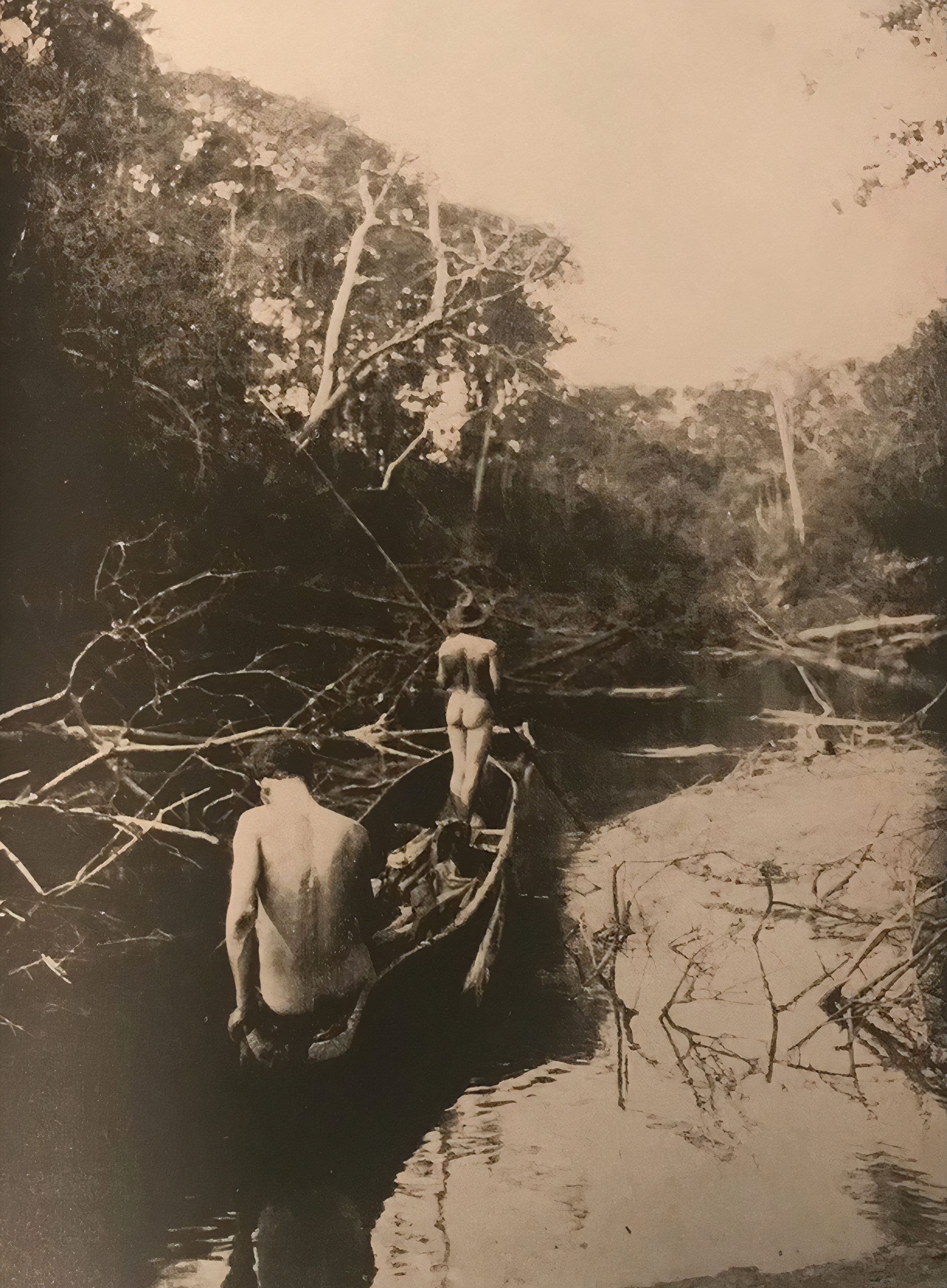

Arriving in Brazil “knowing no word of Portuguese”, the expedition did not find Fawcett, or his remains, or reach anywhere near where he was supposed to have disappeared. They meet no indigenous peoples along the banks of the upper Tapirapé river where they followed the tributary of the Araguaia River, only seeing smoke from the presumed fires of “Indians” in the far-distance. The landscape there, apart from the thick jungle along the river banks, was of rough grass plains. They were abandoned by their two hired Tapirapé guides, and Neville Priestly had to return to their base at an empty Dominican missionary’s shack on the steep river bank because of a foot infection.

Fleming dismisses the tales of the man-eating piranhas. In the upriver of the Tapirapé the commonest fish were the “black piranhas, whose reputation both for savagery and succulence stands higher than the ordinary variety’s. All day we waded among them…We derived what comfort we could from the belief that we were exposing a fallacy…how these cruel and undeniably imposing teeth could cut you to ribbons in a trice…The memory lent a certain irony to the sight of the man-eating shoals which slipped past in the narrow passage within a few feet of our unprotected thighs.”

They were, however, plagued by mosquitos, which attacked them ferociously. But apart from the mosquitos there were “no Indians, no jaguars. We saw nothing more formidable than a toad, detected in the act of climbing into my pocket as l slept. If l knew my job, l should say this was a man-eating toad; but l cannot slander so trustful a creature.” Fleming described the tales of the fearsome Amazonian alligator as “a fraud.”

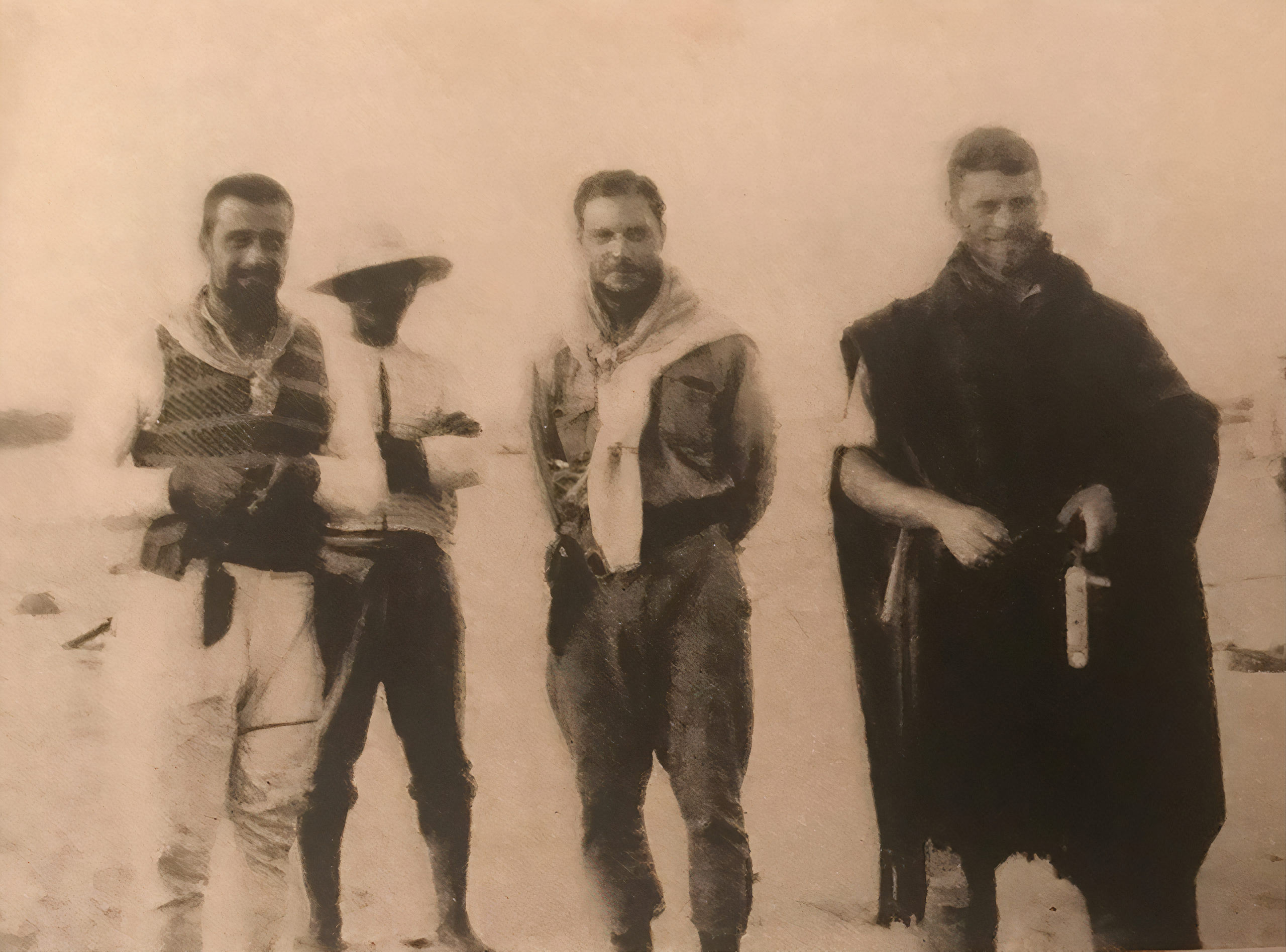

Fleming had acquired a companion he had met randomly on the Gower Street in London. Roger Pettiward, who made “the whole expedition at once more plausible.” He had some “technical qualifications” The expedition took the ship to Rio de Janeiro in 1932 six strong. They were warned by the British ambassador in Rio de Janeiro that “General Rondon has been publishing the severest strictures on foreign explorers in Brazil, whose intentions he considers suspect..”

General Cândido Rondon was no mean adversary. He had since 1910 been the head of the Brazilian government’s Indian protection agency (SPI later FUNAI) and had laid the first telegraph lines across Mato Grosso and had accompanied the former US President Theodore Roosevelt on his fraught “scientific” expedition down the “river of doubt” in 1913-1914, which was Roosevelt’s most difficult expeditions. Only Rondon did not suffer from illness and malaria. He had an indigenous forebear.

The state of Rondônia was named in his honor in 1943. (Rondon will be the subject of a new biography to be published later this year by Larry Rohter, the former longtime “New York Times” correspondent in Brazil.) The “cerrado” of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul (the cerrado is tropical savanna which covers the two states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, Tocantins, and Goiás, is today mostly cleared for grazing cattle and the region is a major exporter of soya and frozen meat and is the home to vast agro-business empires. If Mato Grosso were a nation, it would rank third in the world after Brazil and the USA in soya exports (China is the major market by far).

The contact for Fleming’s expedition in Brazil was a Major George Lewy Pringle (not his real name Fleming tells us). Major Pingle was an American citizen holding – he claimed – a commission from the Peruvian army. According to Pingle he had run away from his home in Kentucky at the age of 15 and joined a circus and toured the Southern States, crossing the Mexican border, and had then travelled widely in Mexico, Yucatan (where he nearly died of fever), Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Brazil. Major Pingle was Fleming said “going to be the Key Man.” He was Fleming writes “a tall, thin man of about 40, with a ragged moustache and phenomenally small ears. There is something of a camel in his gait, and he has that short, mouse-coloured hair which looks as if it never grows.”

Major Pingle provides the straight man to Fleming throughout the journey from Rio de Janeiro to São Paulo, and from São Paulo overland to Aranguaia river, where they quarreled on the island of Bananal. Pingle refused to go any further. And he controlled the purse strings. Fleming was determined to go on. Then after his unsuccessful search up the tributary for the elusive Fawcett, Fleming and Roger Pettiward and Neville Priestley, and their paid Brazilian guides, Queiroz, Camaira, and Camariao, traveled down the Araguaia River. They met Oscar, Cassio and Berman there, three young “men of good birth from São Paulo” as well as friendly Dominican missionaries who received them warmly and feed them. Herman (20), Oscar (22) and Cassio (21) were “cheerful, aimless vagabonds.”

Fleming liked them very much. Major Pingle did not. He thought they were spies from the dreaded “press”, which was Major Pingle’s principal bugbear. Herman was “fair, and extremely good-looking, much more like a Scandinavian than a South American. Cassio was dark, and had a pleasant boyish way (his father had been the Governor of São Paulo in 1924)” Oscar..was “old-fashioned”

But he spoke English having studied law in Manchester. 1924 was important in São Paulo’s history. It was the year a revolt of junior army officers in São Paulo and the Governor, Carlos de Campos, was forced to retreat to the outskirts of the city. Federal troops intervened to restore him.

The rebels who escaped joined former army captain Luis Carlos Prestes in one of the most mythologized episodes in Brazilian history, the Prestes Column, which traversed the far interior of Brazil and Mato Grosso in a guerrilla campaign. The survivors eventually disbanded in Bolivia and Paraguay in 1927. From 1943 until 1980, Prestes was the long-term general secretary of the communist party of Brazil (PCdoB). His companion, Olga Banario, a German-Brazilian communist militant, was extradited to Nazi Germany in 1938, and in 1942 was gassed along with hundreds of other female prisoners.

Fleming’s arrival in São Paulo in 1932 coincided with the outbreak of the Paulista constitutional revolution, and en-route to the Anarquia River, they had passed troops mobilising, and road bocks on the bridge between São and Minas Gerais. In fact Fleming’s expedition in search of Colonel Fawcett took place exactly between the beginning of the Paulista revolution in June 1923 and its defeat by federal forces in October.

But Fleming spoke no Portuguese (which is why Major Pingle was so important to the whole enterprise since he did). So it is not surprising perhaps that Peter Fleming missed almost entirely this pivotal event in Brazilian history which led to the consolidation of the dictatorship of Getulio Vargas and the establishment of Vargas’s fascistic “New State” in 1937.

When Fleming and his party encountered Major Pingle again on the beach at Bananal island on their return from the Tapirapé he gave them 550 mil-réis (about £10), and then pushed off with two of the original team leaving a very angry Fleming behind. It was a 1000 miles to the sea. Eventually Peter Fleming arrived at the intersection of the Araguaia river with the Tocantins river and landed at Marabá. From Marabá they would continue on towards the Amazon and by a narrow channel to Belém. They arrived in advance of Major Pingle which delighted them (they had be racing to beat him to Belém). They arrived just in time to catch the delayed steamship the “Pancras,” that would take them back home to England.

Peter Fleming had been stuck at Marabá where they awaited a launch to take them on downstream. “How we hated Marabá. There was nothing to do. Every afternoon it rained. Most of the time we lay on our blankets on the floor, glumly enduring delay. The room in which we lived was dark and very dirty..the fire-ants were painful.” They were desperate for money. Neville repaired their shotgun which they sold to a Syrian (“there a lot of in the interior of Brazil”). Queiroz, their Brazilian guide, sold their “batalhão” (a four oared, clinker-boat, 20-30 feet long) which had transported them down the Araguaia and Tocantins rivers to Marabá.

In Marabá the launch for onward journey was owned by a colonel Raimundo Tola who had made his fortune during the rubber boom and now commanded the local nut trade. Fleming found him “mildly repellant. He was dressed in a frogged pajama jacket, a straw hat, dirty white trousers and an umbrella. His face was equine and flabby…he had soft, heavy hands, and his manner towards us, even for a low-class Brazilian, almost incredibly unreasonable.” The inhabitants of Marabá “treated us as a cross between a zoo and a museum.”

For Fleming “The Day After Tomorrow” summarized Tola’s endless procrastinations. Fleming eventually took the initiative into their own hands and Neville dismantled and reassembled the engine of the launch, and at last after another day’s delay they were eventually on their way “beneath a cargo of nuts and hides, twenty passengers, one pig, one turkey, one sheep, four parrots, two dogs, and a turtle.” Fleming wrote: “With a look of inexpressible loathing I watched Marabá disappear around a bend on the river.”

They took a lorry around the rapids and waterfalls eventually arrived at Alcobaca where the local big shot, a doctor Amyntas, proved to much more helpful than “that exquisitely dishonourable man” Colonel Tola had been in Marabá. “Doctor Amyntas was to Alcobaca what Henry Ford is to Detroit” the fellow passengers had told Fleming. “Doctor Amyntas was a twinkling little man with a sudden unabashed pot belly…he wore clean white ducks and a flat hat; and of course, he carried an umbrella.” Fleming observed: “He would have been well cast as what is, l believe, professionally known as a Small Bishop, in one of Shakespeare’s historical plays.” Fleming and his companions got a passage on the launch for Belém.

In 1966 and 1967 when l was living in Copacabana in Rio de Janeiro l would be visited often (and unannounced) by a professor Michael McCarthy. He was quite old and would fall asleep without notice in the middle of a conversation. He had originally come to Brazil to work on educational reform. But this aspiration ended with the military coup of 1964. When l knew him he had be consigned to very small room in the very far corner of the Brazilian pedagogical institute in Botafogo. I visited him there and was introduced to the director. The next day a whole load of Brazilian translations of illustrated books by European travellers in Brazil was delivered to my apartment (these now form part of the Kenneth Maxwell collection of books on Brazil and Portugal at the library of St. John’s College, Cambridge).

Professor McCarthy said he had been sitting on the sandbank at Palm Beach in Florida when an angry Joseph Kennedy had shooed him away as he was trespassing on the Kennedy’s “private” property. He had also travelled extensively in the Amazon Basin and said there was gold and iron ore and untold mineral riches hidden there. He also believed that Rio de Janeiro would slip off the Continental shelf into the Atlantic Ocean. The last time l saw him in the distance was in Urca where cable cars begin the assent to the Sugar Loaf Mountain. He was obsessively peeling posters off a lamp post. I thought he was quite mad. But he was perfectly correct about the mineral riches in the Amazon basin, and particularly those in the mountains to the west of Macapá, where Peter Fleming had spent his involuntary and uncomfortable sojourn, frustrated by the endless procrastinations of Colonel Tola.

In the late 1960’s a U.S. Steel helicopter landed by accident on a hill in the Carajás range to refuel. The passengers noted that the hill contained iron ore content of 66%. These proved to be 7.2 billion metric tonnes of proven and possible reserves. They are the richest and most concentrated reserves in the world. The Brazilian company Vale (CVRD) now operates the Carajás iron ore mine in a huge open-pit operation. Between 1974 and 1985 an enormous Hydroelectric dam and turbines were constructed across the Tocantins river at Tucurui. The turbines were designed in France where six were constructed and six more constructed in Brazil. The vast dam improved navigation on the Tocantins avoiding the rapids and waterfalls which had obliged Peter Fleming and his party in 1932 to take the overland truck route to bypass them.

The Tucurui hydroelectric plant supplies the States of Pará, Maranhão and Tocantins, and allows the exploitation of the Bauxite mines and aluminum production. In 1979 the largest gold deposit in the world was discovered in the Serra Pelada also to the east of Marabá. Tens of thousands of “garimpeiros” (wildcat gold miners) flooded in to work the huge pit by hand. Sebastião Salgado, the Brazilian photographer, recorded this enormous human ant-hill of frenetic activity. The area saw influx of prostitutes and alcohol and witnessed 60-80 murders a week provoking a military takeover. The huge pit is now a deep abandoned waterlogged gash in the landscape.

The Carajá iron ore operation, and the manganese, copper, tin, nickel, and aluminum in the area, led to the construction of 890 km railroad from Marabá to the east to the port of Madeira near São Luís on the Atlantic coast in Maranhão. The Carajás railways now transports 120 million tons of cargo and 350,000 passengers a year. The mining operations led to the influx of settlers, ranchers, charcoal burners, loggers, which has accelerated deforestation and the displacement of the indigenous populations. Large parts of the forest have been replaced by the pastures and farms. All a far cry from the dismal little nut transporting river port Peter Fleming hated so much when he was stuck there in 1923.

But the Araguaia-Tocantins has a more sinister memory today. It was the location of the guerrilla campaign of the Brazilian Communist Party between 1972 and 1974 and the violent repression of the movement by the Brazilian military regime. 15,000 troops were mobilised to annihilate 70 guerrillas. 3 guerrilla units spread over 30,000 km (the size of Holland) were “disappeared” in the course of three military operations. There were officially 84 deaths, which included 69 guerrillas, 11 military, and 4 rural dwellers in the “Bico do Papagaio” between Tocantins, Para and Maranhão. The resting places of many of the dead guerrillas remains unknown to this day. Like so much of the record of the Brazilian military regime there has never been any formal acknowledgment or accountability. Certainly not under the rule of the former Brazilian president and former army captain, Jair Bolsonaro.

Peter Fleming went on to play a significant and unconventional role during WW2 when he served as a colonel in the grenadier guards in Norway, and in England where he organized for a guerrilla campaign against a potential Nazi occupation by burying arms and explosives for use behind enemy lines, and he did the same in Greece.

Later he was moved to the Asian theatre where he devised a dummy staff, and a complex series of battle plans that the Japanese believed was the true British plan for battle for India and Burma. He married to Celia Johnson, an actress best known for her parts in the films “Brief Encounters” and “The Prime of Miss Jean Brody”. Peter Fleming died at the age of 64 in 1971 while grouse hunting in Black Mountain, Argyllshire, Scotland. His “Brazilian Adventure” is still in print.