Porcupine Defense: How Maritime Autonomous Systems Can Enhance Deterrence in the Pacific

In a recent article about how the Philippines are enhancing their defense capabilities, I focused on innovative ways they were using maritime autonomous systems integrated into their overall defense approach.

That article was entitled, “U.S.-Philippines Military Cooperation: Fast Boat Bases and Unmanned Systems Contribute to South China Sea Strategy.” The article looked at the expansion of U.S.-Philippines military cooperation in response to heightened tensions in the South China Sea, highlighted by new fast boat bases, upgrades to naval facilities, and the deployment of advanced unmanned surface vessels to the Philippine Navy. These efforts, enabled by U.S. funding and embedded training personnel, are designed to enhance maritime domain awareness and rapid response capabilities, strengthening deterrence against increasingly aggressive Chinese maritime actions.

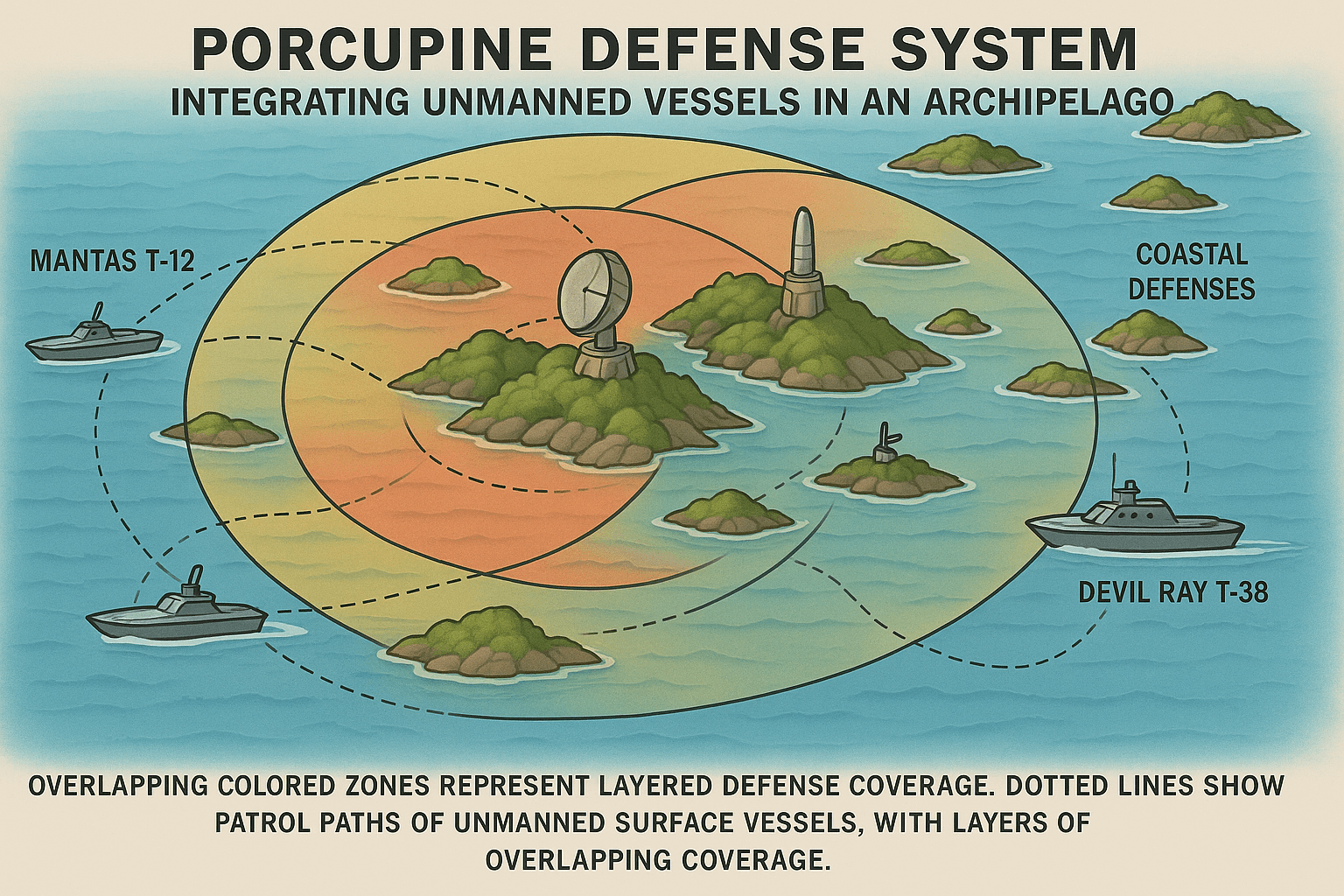

In effect, the emphasis is upon a porcupine defense strategy one which is built around crafting defense geometries with various axis of operations enabling them to complicate the attack profiles of an adversary. By so doing, these new approaches can provide the defender with a range of axis points from which to launch capabilities to disrupt the attacker and make it increasingly difficult for him to have a well-planned, timely defeat strategy.

I received very interesting responses from both Secretary Michael Wynne and Chris Morton of IFS. And based on those reactions, and what I wrote in the initial article, I decided to revist the subject introduced in that article.

Now let me revisit my argument and incorporate their insights.

The Philippines has embarked on a porcupine defense strategy or one that fundamentally disrupts traditional attack calculations through innovative use of maritime autonomous systems. This approach, as Secretary Wynne aptly characterized it, focuses on acquiring “small, cheap, and independent” means to execute enhanced defense.

The Philippines is deploying networks of unmanned surface vessels (USVs), unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and land-based missile systems that create a new defense geometry which provides them with multiple axis points from which to launch disruptive capabilities.

As Chris Morton of IFS observed: “Simply the fact that we can hold at risk Chinese manned vessels with USVs and Starlink is mind blowing—and I think we’d characterize it as an ‘economy of force’ mission.”

The Philippines’ approach is particularly suited to their unique geographic challenges. With over 7,000 islands and vast maritime domains to defend, traditional naval strategies would require prohibitively expensive fleets. Instead, their Comprehensive Archipelagic Defense Concept (CADC) leverages autonomous systems to create persistent surveillance and response capabilities across their territorial waters.

Lieutenant General “Stick” Rudder, former MARFORPAC Commander, explains the strategic logic: “Given the size of the Philippine Navy and the wide expanse of coverage required, conventional Navy and Coast Guard ships must be augmented with unmanned capabilities.” These systems provide “an affordable, capable, and persistent Navy and Marine Corps addition to deliver the kind of ISR needed.”

The integration of land-based anti-ship missiles with maritime ISR capabilities creates what Rudder describes as a “credible 3-5 year program of rapidly enhancing Filipino defense.” This timeline stands in stark contrast to traditional defense procurement cycles that often span decades.

The porcupine defense strategy succeeds because it fundamentally alters the cost-benefit calculation for potential aggressors. As Secretary Wynne noted, “You need to buy more quills, and you can’t grow them fast enough for the porcupine defending itself.” Each autonomous platform represents a relatively inexpensive asset that can nonetheless pose significant threats to much more valuable manned vessels.

This asymmetric advantage extends beyond mere economics. Autonomous systems can operate in contested environments where human-crewed vessels would face unacceptable risks. They can maintain persistent presence, operate in swarms that overwhelm traditional defensive systems, and be much more rapidly replaced if destroyed than legacy capital ships.

The Philippine approach offers valuable lessons for U.S. allies facing similar challenges. Rather than attempting to match adversaries ship-for-ship or missile-for-missile, nations can leverage autonomous systems to create defensive networks that are both more resilient and more cost-effective than traditional approaches.

The Philippines’ approach succeeds because it integrates cutting-edge technology with tactical innovation. The Maritime Security Consortium, providing up to $95 million annually through U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, enables rapid deployment of advanced systems without the decades-long acquisition cycles typical of traditional naval procurement.

Key technological enablers include:

- Starlink Communications: Real-time data transfer and remote operation capabilities allow operators to control platforms beyond line-of-sight, extending the operational reach of defensive networks.

- Autonomous Navigation: Advanced AI systems enable platforms to operate independently while maintaining network connectivity, creating persistent presence without constant human oversight.

- Modular Payloads: Systems like the Devil Ray T-38, capable of carrying 4,000 pounds of payload at speeds exceeding 70 knots, can be rapidly reconfigured for different mission requirements.

Operational Implementation: Task Force Ayungin

The establishment of Task Force Ayungin named after the Philippine designation for Second Thomas Shoal demonstrates how this strategy translates into operational capability. Based in Palawan and operating within the Command and Control Fusion Center at Western Command, the task force provides technical assistance for Philippine USV operations while maintaining Philippine operational sovereignty.

This model addresses a critical challenge in modern alliance relationships: how to provide advanced capabilities while respecting partner nation autonomy. U.S. officials have clarified that while the task force provides training and intelligence support, actual missions remain “purely Philippine operations.”

The Philippines’ strategy succeeds because it’s supported by strategically positioned infrastructure designed for rapid deployment. The new fast boat base in Quezon, just 160 miles from Second Thomas Shoal, exemplifies this approach. Designed to launch watercraft within 15 minutes, the facility supports distributed operations while maintaining the flexibility to respond to emerging threats.

Similarly, the upgraded Naval Detachment Oyster Bay includes maintenance capabilities specifically designed for unmanned platforms, ensuring sustained operations without dependence on major naval bases that present attractive targets for adversaries.

The porcupine defense strategy represents more than just a cost-effective alternative to traditional naval power. It fundamentally changes the nature of maritime deterrence. By creating defensive networks that are difficult to target comprehensively, the Philippines makes the cost of successful attack extremely high while keeping their own investment relatively modest.

The Philippine model is attracting attention from allies and partners worldwide. Recent visits by Italian and German naval forces demonstrate growing international interest in this approach, while the trilateral framework developing between the United States, Japan, and Philippines suggests broader adoption of distributed defense concepts.

This strategy also aligns with evolving U.S. military doctrine emphasizing distributed operations and allied innovation. Rather than depending solely on American platforms and presence, the Philippine approach creates indigenous capabilities that complement rather than compete with traditional allied assets.

Perhaps most significantly, the porcupine defense demonstrates that technological innovation can overcome resource disparities. The Philippines cannot match China’s naval shipbuilding capacity or defense spending, but they can deploy systems that hold Chinese assets at risk while operating within sustainable budget constraints.

The Maritime Security Consortium model, using joint exercises like Balikatan to demonstrate and deliver systems rapidly, represents a new paradigm for defense cooperation that emphasizes capability delivery over traditional arms sales.

The Philippine experience offers a blueprint for other nations facing similar strategic challenges. By focusing on “small, cheap, and independent” capabilities integrated into coherent defensive networks, smaller nations can create credible deterrence without bankrupting their defense budgets.

This approach may prove particularly relevant as maritime tensions increase globally and traditional naval platforms become increasingly expensive and vulnerable to emerging threats.

The porcupine defense strategy emerging in the Philippines represents more than tactical innovation. It’s a fundamental reimagining of how smaller nations can maintain sovereignty in an era of great power competition. By growing more quills faster than adversaries can plan to remove them, the Philippines is proving that strategic creativity can overcome material disadvantages.

As Chris Morton’s observation suggests, the ability to hold major naval assets at risk using relatively inexpensive autonomous systems represents a “mind blowing” shift in maritime power dynamics and is one that may define the future of naval warfare in contested waters worldwide.

The featured image was geneerated by an AI program..

The quotes from LtGen (Retired) Rudder were taken from my interview with him contained in the following article:

The Philippine Defense Strategic Opportunity: Enabling Allied and Partner Innovation

The earlier article which was the launch point for this one was the following:

A Paradigm Shift in Maritime Operations: Autonomous Systems and Their Impact