The Portuguese in the Persian Gulf: Hormuz, Bahrain and Mosul

Prologue: When visiting Bahrain recently, we visited the Portuguese fort. Naturally, when I returned to the United States, I talked with Professor Maxwell about the experience and asked if he would be willing to look back at the Portuguese initial engagement in the Gulf. And it is good thing I did, because it turns out that the Portuguese established a trading and choke point template that in many ways continues until today.

The Editor

The Portuguese initiated European seaborne contact with Asia in May 1498 when the fleet of Vasco da Gama reached Calicut on the malabar coast of India.

By rounding the Cape of Good Hope, the Portuguese established the passage between the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean.

Over the next three decades the Portuguese established a chain of fortified trading posts reaching from Mozambique and Malindi in Africa, to Goa in India, to Ceylon, to Malaca on the Malay peninsula, to Macao in China at the mouth of the Pearl River, and after 1543 they established an outpost in Nagasaki in Southern Japan.

The overwhelming objective of the Portuguese was trade: Pepper, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg.

Religion followed. They soon established a round trip route between India and Lisbon known as the “Carreira da Índia.”

The voyage lasted about six months, the fleets leaving Lisbon in March or April with an average of twelve or thirteen ships.

In 1510 Goa became the capital of the Portuguese “State of India.” (Estado da India). The Portuguese established fortresses along the Canara and Malabar coasts where they were interested in cinnamon. They participated in the spice trade (pepper, cinnamon, and cloves).

The return fleets left Cochin and Goa at the beginning of the year, with the average cargo at the beginning of the sixteenth century, of between 7,000 to 10,000 hundredweights.

Vasco da Gama, with the title of “Admiral of the Seas of Arabia, Persia and India” returned to Lisbon in 1503 from his second voyage with 13 ships and 1,200 tonnes (metric tons) of pepper.

In 1511 Albuquerque sent an expedition to the Moluccas (the Maluku islands in present day Indonesia) where cloves, the aromatic dried flower buds of a tree in the family of myrtaceae, syzgium aromaticum, were grown, a valuable and much much sought after spice.

In 1513 the first Portuguese arrived in China, though it was only in 1557 that their presence in Macao was sanctioned by the Chinese. It was from Macao that regular voyages to Japan took place.

The Portuguese introduced firearms to Japan as well as medicine, astronomy, navigation and shipbuilding. Their Christian missions were also successful, making more than 100,000 converts, while running a valuable silk trade from Macau, and advising the rising power of the Tokugawa shogunate on military tactics. In the 1630s friction resulted in the great massacre of Christians in 1638, and the banning of all Portuguese from Japan in 1639.

During the early 16th century Portuguese superiority in ships, artillery, military techniques, and fortress construction, made it possible for a few thousand Portuguese to sustain a seaborne enterprise stretching from East Africa to Japan.

This thalassocracy was always dependent on the indifference to maritime affairs by China, and the divisions in the Asian world.1

Portuguese control was never complete, especially on the land, where the great empires of the Ottomans in the Balkans and Anatolia, the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria, the Safavids in Iran and Iraq, and the Mughals in India, dominated.

In the Indian Ocean Muslim merchant communities were well established when the Portuguese arrived. The massive pilgrimages of Muslims to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina in the Arabian penunsula produced a cyclical pattern of Indian ocean-going voyages of thousands of people.

The Portuguese also relied on local informants, particularly Jewish converts living in East Africa and Asia during the early years.

The Portuguese brought a combination of state and merchant interests together and introduced a warrior culture and a ruthless military commitment.

They did not hesitate to use force.

In addition to building fortresses the Portuguese established a system of “cartazas” which were “authorisations” essentially “safe conducts” to allies and denied to enemies, which allowed non-Portuguese ships to circulate without being attacked by the Portuguese.

Essentially the Portuguese coerced the local merchants into paying them fees while seizing the most lucrative trade routes for themselves.

While there were no European competitors this system worked.

The most important long term contribution of the Portuguese in Asia, however, was the identification and mapping out of the strategic choke points: The Strait of Hormuz still one of the world’s most important maritime transportation routes, and the Strait of Malacca, still the main shipping route between the Indian and the Pacific Oceans.

With their more powerful ships and cannons, the Portuguese established themselves by force of their superior military technology at these key points for trade and of geo-strategic influence. Where the Portuguese had led, later on the Dutch East India Company and the English East India Company followed.

The Persian Gulf and the Red Sea were an essential part of the Portuguese scheme to control the trade of the Indian Ocean, and in particular to break the trade network created by Muslims in the Indian Ocean.

The Portuguese had attempted to establish a base in the island of Socotra, when in 1507, a Portuguese fleet commanded by Tristão da Cunha, with Afonso de Albuquerque, captured the port of Sug after a fierce battle. Tomás Fernandes started to build a fort there but lack of food and a poor harbour led the Portuguese to abandon the the island four years later.

The Portuguese were unable to control access to the Red Sea.

The Mameluke sultanate of Egypt, with the support of the Venetians, prepared a huge Armanda and a fierce battle took place in 1509 off the coast of Diu, where the Portuguese were victorious. Egypt was conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1517 and they seized Basra in 1546.

Albuquerque failed to capture Aden at the entrance to the Red Sea, making it impossible for the Portuguese to control the goods passing through the straight of Bab-el-Mandeb. In 1538 the Ottomans captured Aden which they held until the 1630s

Aden and Hormuz dominated the maritime commerce of the Middle East controlling the entrance to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf and linking the overland routes between the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean.

In the Persian Gulf the Portuguese were more successful.

In 1514 the fleet of Pêro de Albuquerque reached the island of Bahrain, and in 1515 Afonso de Albuquerque returned to Hormuz.

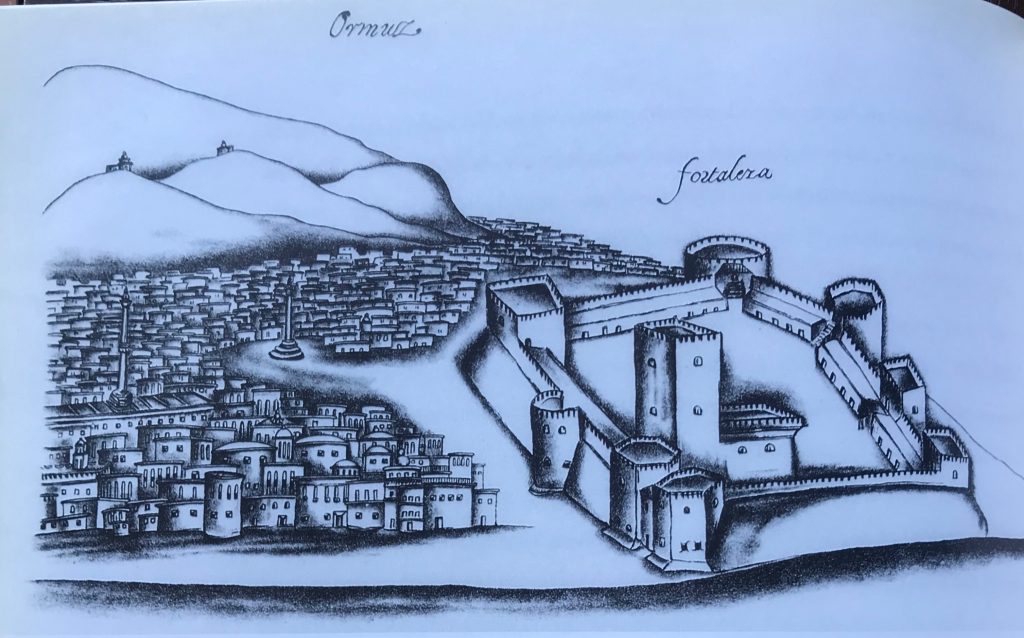

The Portuguese built fortress on Hormuz which became their main base.

Together with Muscat and Curiate in Oman and Bahrain in the Persian Gulf, Hormuz became the base from which the Portuguese attempted to control access to the trading routes over land between the Indian Ocean and Europe via Basra, Bagdad, Aleppo and Tripoli, and to the eastern Mediterranean.

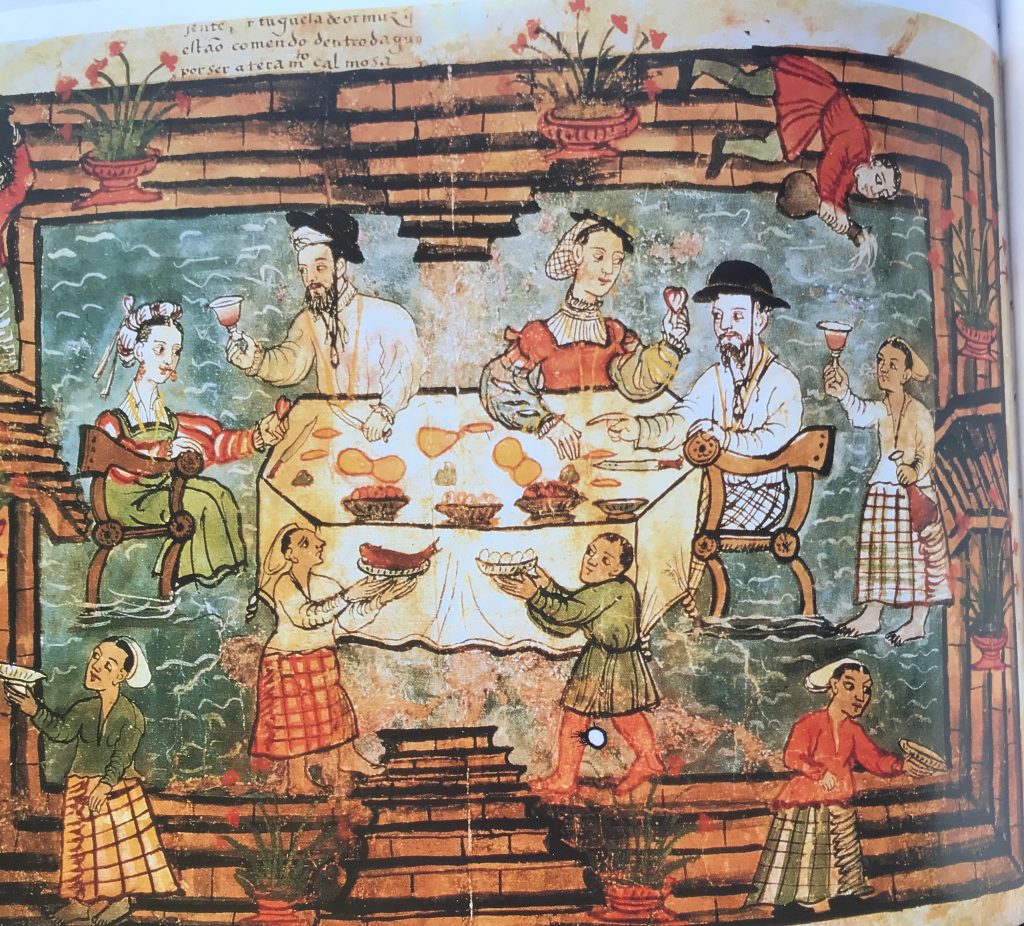

Hormuz with a population of Arabs, Persians, Indians, Jews, and Christians, was where Portuguese control of the customs house (bangsar) placed the Portuguese at the crossroads of the Iranian, Arab, and Indian worlds.

The key for the Portuguese in Asia was to control the sea routes.

Dom Francisco de Almeida, the first viceroy of India between 1505 and 1509, put this paramount interest in a letter to King Manuel of Portugal. It was necessary he told the King, that “all our might be in the sea. For if we are not mighty there, everything will be against us, as long as you be mighty in the sea, India will be yours, and if you are not in the sea, little will fortresses on land serve you.”

The objective of Afonso de Albuquerque in the Persian Gulf in 1507 was to control and block the Muslim trading routes which allowed valuable Asian goods to be taken to the eastern Mediterranean, and from Hormuz, at the entrance to the Persian Gulf, the customs house controlled by the Portuguese, oversaw a lucrative trade throughout the Gulf region.

An Omani pilot, Ahmad bin Majid, had guided Vasco da Gama on his first journey from East Africa to Calicut. Muscat on the Omani coast and Bahrain in the Gulf and their fortresses became a key part of this network. In Muscat the Portuguese established an armed presence in 1508.

Defended by a small number of Portuguese officers and locally recruited auxiliaries, Muscat became the most strongly fortified base on the Arabian peninsula.

The Portuguese remained there until 1650 when Muscat was recaptured by the Omanis of the al-Ya’ruba dynasty.

On the island in Bahrain, where the Khalife family have ruled since 1783, the Portuguese constructed a huge stronghold with towers joined by a fortified wall.

The Bahrain Island was a key strategic point on the route between Hormuz and Basra and from which the trade along the Persian Gulf could be monitored and controlled.

The Portuguese fortress on Bahrain built on the site of an Arab fort, consists of three huge strongholds and two towers joined by a wall linking the strongholds together, and is surrounded by a trench.

It was first occupied by the Portuguese in 1521 and it was enlarged in 1559.

The Portuguese held Bahrain until they were expelled by Shah Abbas of the Safavid dynasty of the Persian empire in 1602.

The key position of the Portuguese on the island of Hormuz which controlled access to one of the world’s most strategically important choke points was lost to a joint Persian and English army and flotilla in 1622 when some 2000 Portuguese inhabitants were expelled to Muscat.

The featured graphic shows a 1563 map of the Gulf and the Red Sea and showing Bahrain and Hormuz.

About Dr. Kenneth Maxwell:

Footnotes

- A thalassocracy or thalattocracy (from Classical Greek θάλασσα (thalassa) (θάλαττα in Attic Greek), meaning “sea”, and κρατεῖν (kratein), meaning “power”, giving Koine Greekθαλασσοκρατία (thalassokratia), “sea power”) is a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea (such as the Phoenician network of merchant cities) or a seaborne empire. Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thalassocracy