The Disposable Unmanned Warfighter: The Economies of the Battlespace

At the recent , Defence IQ conference on ”Disruptive Technology for Defence Transformation,” held in September 2020, one of the most interesting of the presentations was given by Adam Smith of Intrepid Minds Robotics.

After his presentation, we discussed some of the topics he introduced by one of the virtual linkups which the conference organizers provided for participants in the conference.

Smith is the owner and director of Intrepid Minds Robotics (IMR) Ltd, a UK based company delivering autonomous systems.

According to the moderator in introducing Smith with regard to the argument for robotics and remotes argued why they are being adopted:

“I think a couple of things are clear just to set the scene for him. The first thing is future militaries will be this mix of manned/unmanned and autonomous capability and an evolving program. They’re going to do that for two reasons:

The first reason is unmanned and autonomous capability we’ll make our own policies better, more resilient, larger in many cases, and a more competitive.

Secondly, when we get it right, we’ll make our own forces cheaper because the lead fewer regular people and the acquisition and sustainment costs of a robotic platform ought to be less than a manned platform.

In many ways the killer argument for most ministers of defenses with regard to autonomous capability, the fewer pensions the MOD and other European nations have to pay; as robots don’t have pensions, they are enormously attractive to nations that have to pay for expensive volunteer forces.”

Adam Smith noted at the outset of his presentation, his team have worked in a variety of areas, not just defense.

“What we are very good at is the cross pollination of ideas from these different sectors.”

They are moving their mature products into a production and delivery company associated with the R and D company.

“We build solutions for case studies, not the other way around.”

Smith focused on the question of what the focus of is how you use robotics to what tasks to prevail in which battles and for what overall combat purpose.

In effect, he argued that robotics from his perspective can make its greatest impact on the soft kill targets in a military campaign.

Although he did not say it in these words, he was highlighting the importance of correlating what tool kit you have up against the objectives and tasks you need to achieve to master escalation dominance.

He focused on different “types of soft kills” and how they might occur and affect the combat rhythm and outcomes.

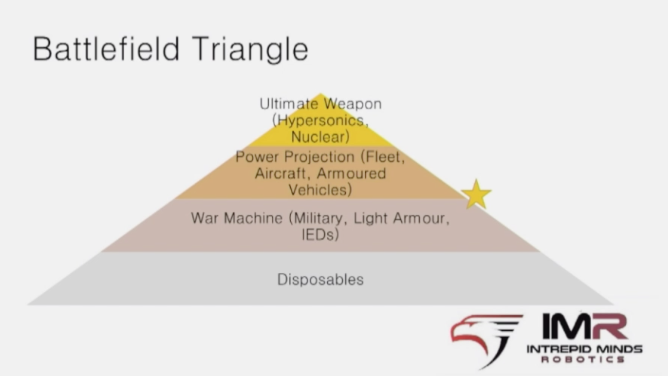

To do that, he presented a very simple model which he referred to as a “battlefield triangle” from which he then discussed how to think through the impact of soft kills on combat dynamics and outcomes.

As he noted: “We’ve come up with this model with pinch points within a multitude of different scenarios, which allow you to either win or lose and give factors that either increase or decrease the chances of victory.”

He then leveraged the model to highlight where he sees unmanned assets as having their most significant potential impact, which is indicated by the star in the diagram.

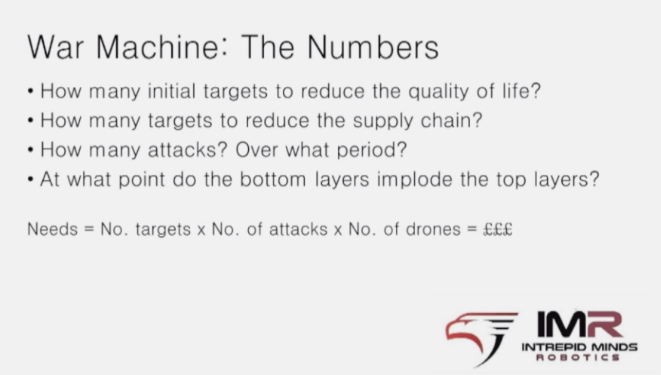

When he came to the discussion of what he referred to as “the war machine,” he discussed it in these terms:

“We call this the need for needs…. we start to look not at two forces hitting each other across the battlefield, but more about what does that group need in order to continue to survive, in order to continue to operate.”

The focus then is upon how unmanned assets can be used for attrition of the basic support structure for the war machine.

“We look at how many initial targets are required to reduce the quality of life.

“Those targets could be the reduction of the supply chain, how many attacks are needed for one type of period.

“Those attacks potentially don’t need to be something that goes in and explodes by its very nature.

“Some kind of kinetic energy going into those locations will cause a disruption.

“At what point does the bottom layers implode the top layers?”

“How much destabilization do you need?

“And again, we’re looking at this from an autonomous point of view, but things like cyber-attacks, fake news, they’ve been used against us, they can be used for us as well.”

“Looking at that, we can then look at the mathematical formula. Needs equals the number of targets multiplied by the number of attacks multiplied by the number of drones. That’s again is a monetary figure.”

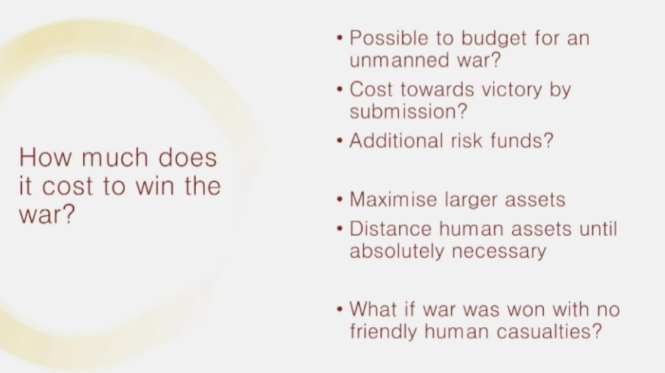

So how much does it cost to win the war?

He posed a great question when addressing payloads for the combat force: Is it possible therefore, as part of the defense review and potential budgeting going forward, to create a cost towards victory by submission?”

“Is there an additional risk fund that can be used if things don’t go exactly to plan, if they don’t go to the mathematical formulas that we’re using.

“And what does that look like as an economic tradeoff for states and how they look at wars in the future? What does this mean for maximizing the larger assets?”

“Can we move them a step back so that we can push all of the unmanned assets forwards, because it is economically viable to go and do so?

“And after they have disrupted the enemy and we then push those larger assets in.

“Is it possible to distance human assets until absolutely necessary?”

“Is it possible that in fact human assets are so far back from the battle lines that you get to the point where battle starts being won with no friendly human casualties? … And if it is, what does than that do to how battles, wars, anything of that type is seen by media, by the general populace.”

“Could it be a case that there is a disruption in another country or there is a particular fight in another country that we win by proxy by sending over our unmanned assets, with no human casualties and that the front page then reads something along the lines of almost like a police state. And there was a disruption we sought to that to disruption there was no casualties and it was resolved. What does that do to the message that is a battle or war in the future?”

“The economy of war suggests that a side will continue until they reach a point where they feel that they can no longer win or compete, and they surrender.

“Our perspective then is not to focus on unmanned systems to do the hard kill, but more, a light touch aimed for the soft kill – take out the utilities, take out the supply chain, let nature and psychology and the influence of all of those things against the enemy, bring them to submission as opposed to a traditional fighting style.”

He then focused on what he identified as key challenges to be able to achieve such an approach.

The first one is manned and unmanned teaming.

“Autonomy is a tool, it’s like a gun, a helmet, or a radio.

“The primary function of a gun is to shoot something, but the secondary and tertiary function of a gun is to shoot it in the air, make a noise, distract, have a problem with purpose and then find others, but make sure that you do what you need to do well. And then from that build trust through the trials.”

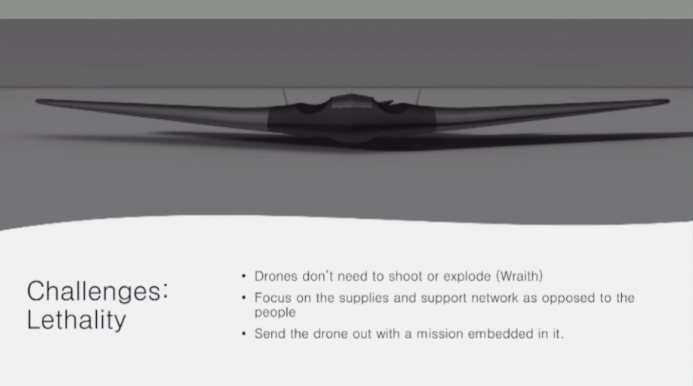

He then highlighted a way to illustrate the soft kill notion.

He did so by using the example of one of the company’s UAS systems focused on going after the defense infrastructure.

Drones do not need to shoot or explode. If a particular drone is designed to have the ability to penetrate utilities or comms installations, whatever it is, it does not need to explode for damage to be caused.

“It will make a lot of damage.

“The focus is on the supplies and support network, as opposed to the actual people.

“If we take out what I’ve already specified, then that will cause an immense amount of disruption.

“Send the drone out with a mission embedded in it.”

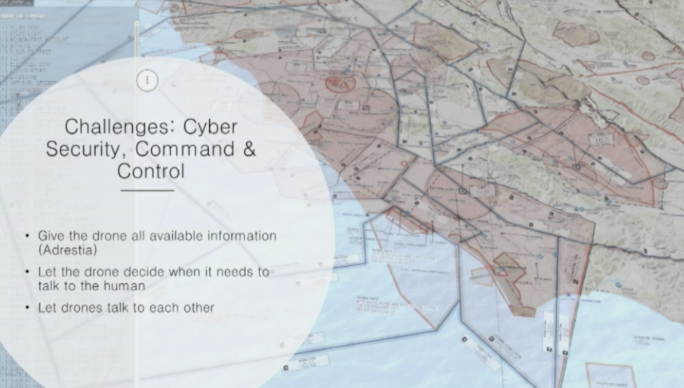

The next challenge he discussed was cyber security and command and control.

He argued that one way to address these challenges is to focus on the mission in very specific terms for the drone, send it out with a mission embedded into it.

“Why not give the drone all of the mission parameters so that it knows what to do?”

He provided a case study of an operational experiment off the Italian coast.

“In the graphic is a particular scene from our C2 system, over Italy, where we’re planning a flight and you can see all of the segregated airspace, that is mapped onto a 3D model…. There’s a link, within the system, that the drone is able to have, that is able to navigate constantly to all of these different changing factors and all of that is embedded into the drone.

“If it’s got this and the micro brain, and it’s operating with AI, ML is already in built into the drone. Let the drone decide when it needs to talk to the human. Not the other way around, there should be a point in the near future where we start to cut those apron strings and realize that the human does not need to be in constant contact with the drone.”

“Let drones talk to each other. Anybody who’s seen two drones or multiple drones talk to each other over in an industrial setting such as a civilian industrial setting, will know that it is very, very quick and actually putting a person in the loop, slows it down, especially from that decision-making process.”

“Ultimately, I completely agreed that the human needs to be in the loop in order to take out the targets or to make very hard decisions. But if what you’re trying to do is achieve a target and you’re running multiple hundreds of drones all at the same time, there needs to be a case of allowing the drones to talk to each other and ultimately taking out those targets, especially if there is the possibility of no human interference.”

The third challenge is cost.

He provided an example of one of the company’s projects which is a hand-based asset which comes in at a base line cost of 2000 pounds and provides very significant capability for the ground forces, operating in a multi-domain manner.

The final challenge addressed was the procurement and development processes whereby unmanned capabilities can be obtained.

Here an argument was made for alternatives to classic acquisition whereby a platform is the focus of a purchase.

Focusing on service contracts provides significantly greater flexibility for the armed forces, whereby they can subscribe to getting a capability, rather than platform acquisition and ownership.

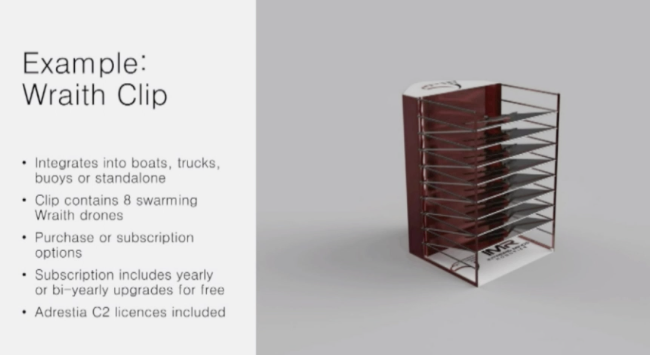

He returned to the Wraith example.

“Wraith … is going to be launched through IMR, through a clip that we’ve developed for it. So, it powers behind it and shoots it out of this clip. And at the moment, we’ve got a clip that has eight Wraiths in it.”

“This clip integrates into boats, integrates into trucks, buoys or standalones. The clip currently has eight swarming grades drones. It shoots these out. It instantly swarms. It instantly gives it the mission parameters and off they go.”

“It could be launched from a boat, to protect a larger asset. It could be shot from a vehicle in order to swarm around a town or take out some utilities. If there’s an incoming fighter, it could be shot out and then give the friendly forces the time to then intersect with our own high-tech technology.”

“We’re looking at as both purchase and subscription options. Subscription includes yearly or bi-yearly upgrades for free. And what that means in practical terms, is if you take it from a mobile phone perspective, you will get a clip of eight Wraiths. If you use all eight Wraiths you can buy some more.

“If you don’t use all eight Wraiths after that two-year contract, we’d take them away. We recycle them and you get the next generation of Wraiths and you keep on going until either you stop your subscription or there’s something else available. “

“All of our Wraiths come with C2 licenses. It comes as a bundle. It comes as that pack that you will typically see with a mobile phone and you get your hardware, you get your operating system.”

In short, more commercial practices in the defense domain is crucial to unleash fully what the unmanned revolution can provide.