Maritime Trade Dependencies and Risks: The Australian Fuel Security Case

Over the course of the fuel security investigations I conducted on behalf of the NRMA, I studied examples of supply chains: from sources all the way through to the ports, and then movement of supplies around the country.

I then examined the analysis that had been conducted to inform the 2011 National Energy Security Assessment (NESA). An analysis that has not been updated since.

The world, the economy, and governments have all changed over the intervening eight years, and still no new NESA to reflect the current environment nor to shape government thinking on energy and security policy.

The Government has, on a number of occasions, committed to developing a new NESA; initially 2015, then 2016, 2017, 2018 and now the undertaking is by the end of 2019.

Australia needs a contemporary and relevant assessment of our energy security, including analysis of a full range of future threat scenarios.

There were only two scenarios the government used for the 2011 NESA in relation to fuel security.

The first, a repeat of the 1970s Middle East oil embargo, and second, the outage of a Singapore refinery for 30 days.

No consideration was made of the risk of conflict in the South China Sea, no examination of oil flows being disrupted by conflict more globally, and no assessment of the implications of critical points of failure within the domestic supply chain. There would be little benefit from getting oil to Australia if it cannot be transported to a refinery or, in turn, to a petrol station.

The 2015 Senate Inquiry into Australia’s liquid fuel security, Australia’s Transport Energy Resilience and Sustainability, explored supply chains and global and domestic risks to transport energy security and resilience.

The importance of realistic scenario modeling was a topic pursued by the Committee, in response to a submission from the Australian Institute of Petroleum that stated that ‘the liquid fuels NESA is not intended to consider ‘national security’ settings and scenarios in which crude oil or product supply is disrupted for an extended period by broadly based military/civil conflict or warfare. Such ‘national security’ scenarios should be considered as part of Defence planning and reviews and are not appropriate for ‘supply’ security assessments or the Energy White Paper.’1

The implication of this statement is that we only need to assess our fuel security risks through the lens of market dynamics.

Such an approach would be naïve at best, and negligent at worst.

The 2015 Senate Inquiry made the following recommendation:

‘The committee recommends that the Australian Government undertake a comprehensive whole-of-government risk assessment of Australia’s fuel supply, availability and vulnerability. The assessment should consider the vulnerabilities in Australia’s fuel supply to possible disruptions resulting from military actions, acts of terrorism, natural disasters, industrial accidents and financial and other structural dislocation. Any other external or domestic circumstance that could interfere with Australia’s fuel supply should also be considered.’ 2

Unfortunately, this recommendation from the Inquiry was not actioned as the Government maintained the existing NESA process was adequate.

So, how does the rest of the developed world manage their fuel security?

Interestingly, with far greater seriousness than does Australia.

As a starting point, we do not even meet our stockholding obligations as a member country under the International Energy Agency (IEA) agreement. Nor does the Australian government mandate that industry hold any minimum level of stocks in reserve.

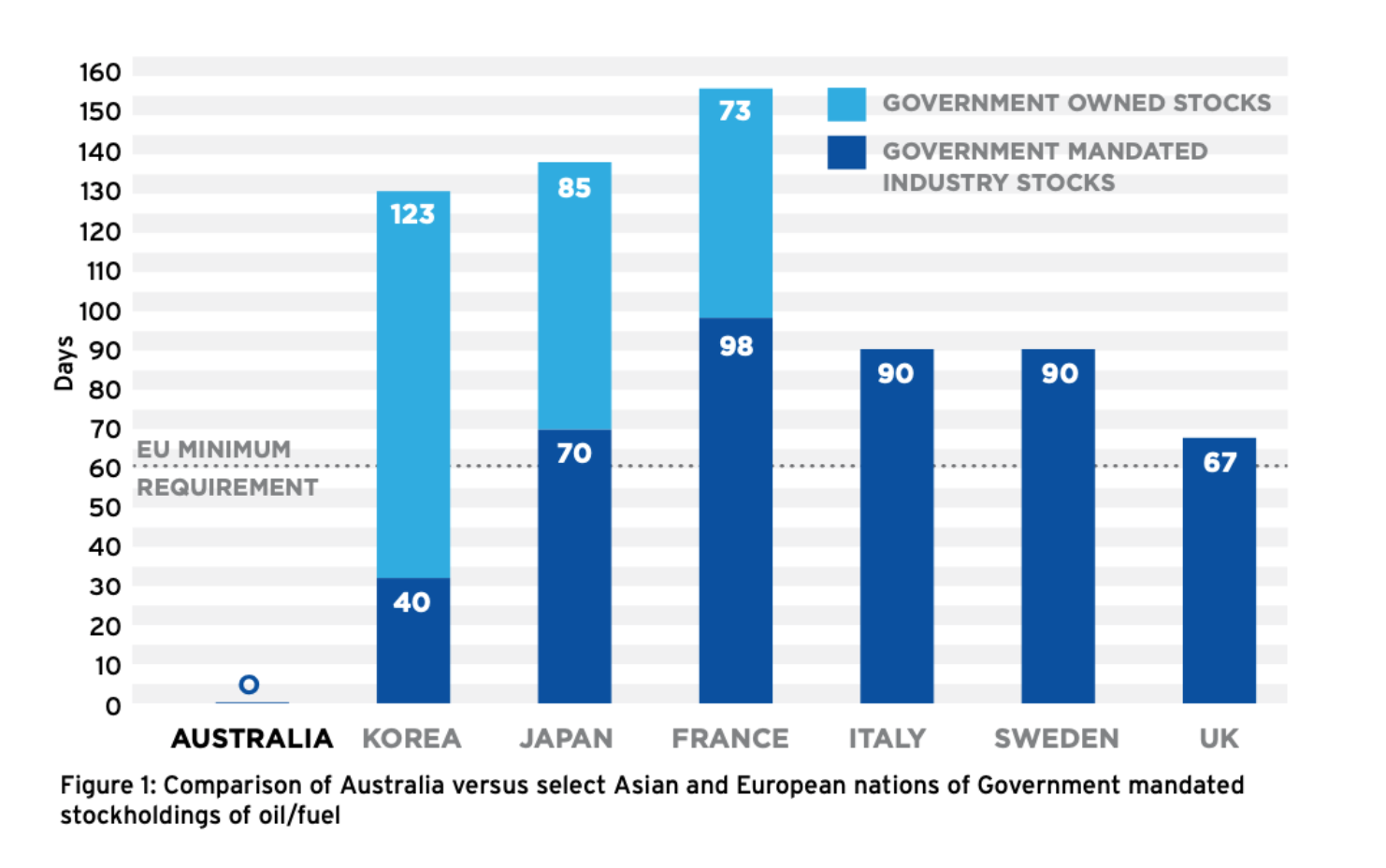

In my 2014 NRMA report, Benchmarking Australia’s Transport Energy Policies, I compared the number of days of government owned stocks of the countries in 2014, as shown in Figure 1.

I posed the question as to why are we so different in Australia?

What do we know that other countries do not know that makes us so confident? Perhaps it reflects the political ideology that “the market will fix everything.”

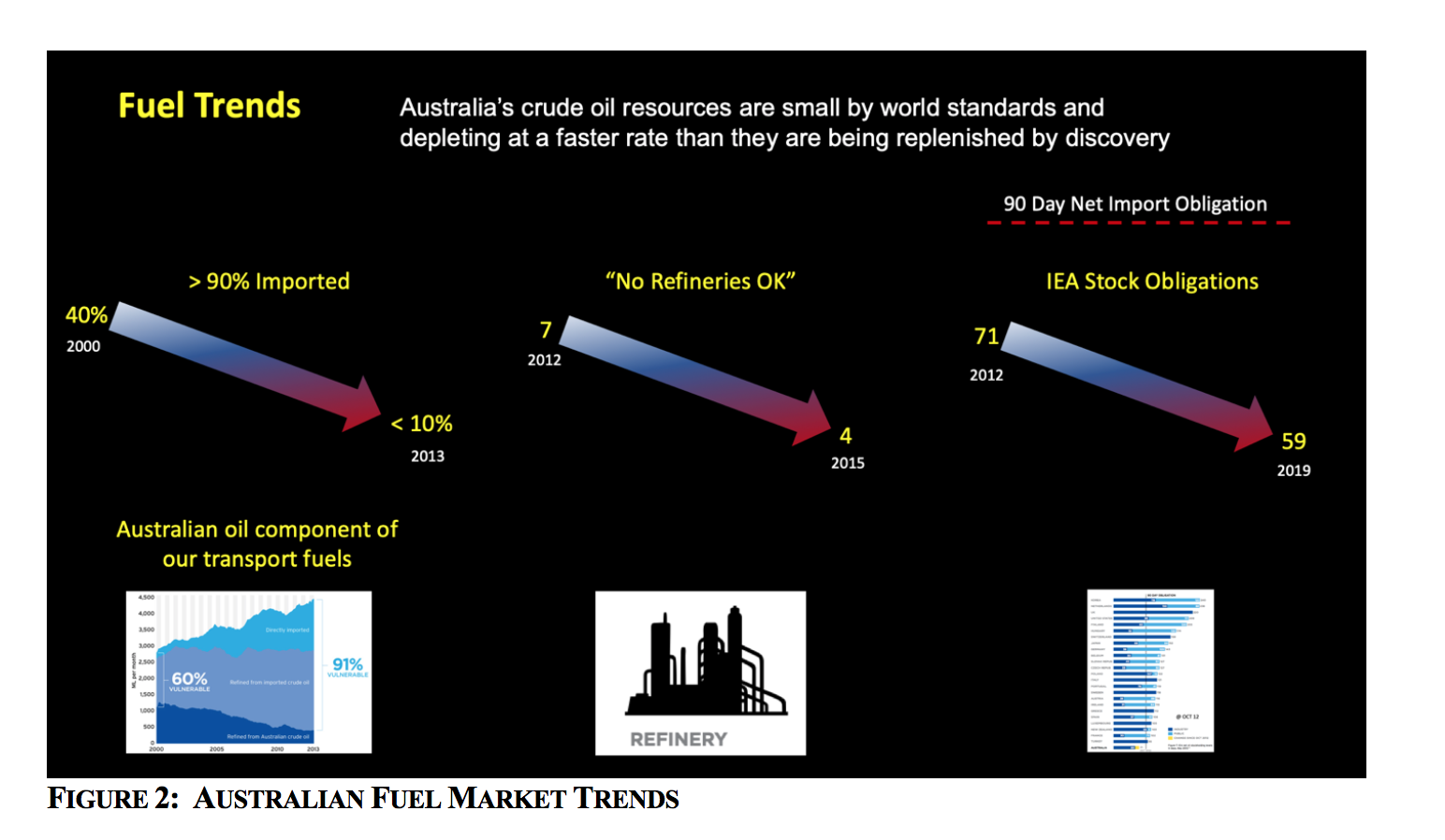

My NRMA reports, and subsequent analysis, highlighted a number of trends, as illustrated in Figure 2:

- Australia’s crude oil resources are small by world standards and depleting at a faster rate than they are being replenished by discovery.

- Australia’s transport fuels import dependency grew from around 60% in 2000 to over 90% by 2013.

- Between 2012 and 2015 there was a 42% loss in Australia’s refining capacity when 3 refineries were closed leaving a total of 4 refineries in country. When asked what the minimum number of refineries should be in Australia to ensure sufficient fuel security and resilience, the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism responded that a “zero” refining capacity in Australia would be acceptable as it would be cheaper to import refined fuels from the Asian refineries.

- Australia has not met its’ stockholding obligations of 90 days of “net imports” under the International Energy Agency (IEA) members agreement, since 2011.

In June 2016, in response to pressure from other IEA member countries, the Australian Government committed to purchase “tickets” (options to buy oil stocks for release to the market) between 2018 -2020 and promised full compliance with IEA stockholding obligations by 2026 … some 15 years after Australia first failed to meet its’ membership obligations.

In September 2017, Parliament passed the Liquid Fuel Emergency Amendment Bill 2017. The 2017 Bill allowed the Australian Government to enter into ‘commercial oil stockholding contracts with Australian and foreign entities … [to purchase] the rights to access oil stocks, i.e. ‘ticketing’’. In 2018 the Government entered into a ticketing agreement with the Netherlands. We now have two to three days under the ticket process in the Netherlands, but still no Government owned stocks for market use in Australia. So, the first purchase of “Government Stocks” was for an option to purchase oil in a foreign country. This had little impact on Australia’s domestic fuel security.

Despite this latest action, Australia, with only 59 days holdings as at July 2019, remains the only country out of 28 member countries that fails to meet its 90-day net oil import stockholding levels.

The world’s ninth-largest energy producer is the lowest and only non-compliant stockholder in the IEA. However, the IEA stockholding figure does not represent real useable fuel that we can put in our cars and trucks.

For example, in June 2019 we had 22 days of diesel stocks in Australia; in the last three years diesel stocks have been in as low as 12 days.

Almost everything in Australia, at some point in its’ lifecycle, needs diesel: for example, our food and pharmaceutical distribution chains, energy systems, emergency power generation, waste removal, construction and transportation, agriculture and our water supply.

In 2018, as part of the Energy Policies of IEA Countries series, the Australia 2018 Review was released. The review concluded that Australia’s oil security policy is based on ensuring the operation of an efficient and flexible oil market.

Accordingly, the country’s liquid fuels market is largely unregulated during business-as-usual. “However, it is less clear how the country would respond in the event of a serious oil supply disruption leading to market failure.” These observations and conclusions do not reflect a coherent approach to energy security nor energy policy in this country.

In 2018, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security review of the Security of Critical Infrastructure Bill 2017, made the following recommendation: ‘The Committee recommends that the Department of Home Affairs, in consultation with the Department of Defence and the Department of the Environment and Energy, review and develop measures to ensure that Australia has a continuous supply of fuel to meet its national security priorities… ‘The Committee considers that the Department should conclude this review within 6 months.’ 3

The Government was to have completed this review in December 2018.

An interim fuel security report was released in February 2019 with a revised delivery date for the final report as end of year 2019 – twelve months late.

As noted previously, this article uses the example of how Government has not adequately assessed the risks related to our fuel security to review how the risks to our Maritime Trade system have been assessed.

Australia clearly lacks a contemporary and relevant assessment of our energy security and there is no apparent appetite for the Government to conduct such a comprehensive assessment.

This conclusion leads to the question of whether of not the Government has been as lax with the assessment of risks to our maritime trade as it has been with fuel security?

National Security and The Market

I contend that the traditional construct of peace and war is outdated.

We live in a world in a continuous spectrum of conflict and we are vulnerable to disruption.

There is no longer a state of ‘business as usual’ or ‘peacetime’ where market forces alone can provide for our security.

A recent example of conflict was the September 2019 attacks on the Saudi oil production facilities impacted around 5% of the worlds daily oil supply. Despite the Saudi Government spending billions of dollars to protect a kingdom built on oil, it could not defend against the relatively small-scale drone and cruise missile attack.

It was somewhat sobering to watch a Saudi official trying to congratulate their air defence forces on defeating recent attacks from ballistic missiles whilst standing in front of the images of burning oil infrastructure.

Whilst the market did adjust to the loss of supply in this specific case, clearly Saudi Arabia’s critical infrastructure is still vulnerable and further attacks which could have major impacts on the global economy and energy security.

Following the Saudi refinery attack, John Rood, the Pentagon’s Under Secretary of Defense for policy pointed out that ‘The threat that we face has developed faster than our own countermeasures … As much progress as we’ve made, if you’re not staying equal to, or making greater progress than, the threat picture, it’s a serious problem.’ 4

The free market cannot prepare Australia for the ‘disasters’ that may be ahead.

It will not build sufficient resilience in our supply chains without appropriate Government regulation and market incentives.

In the case of risks and vulnerabilities related to Australia’s maritime trade, it is necessary to identify, and question, the assumptions that are being made by both the market and the Government.

Maritime Trade Risks and Inquiries

So, what are the risks associated with an interruption to maritime trade?

The world is in the middle of a trade conflict right now between the United States and China. What is the risk to Australia from collateral damage?

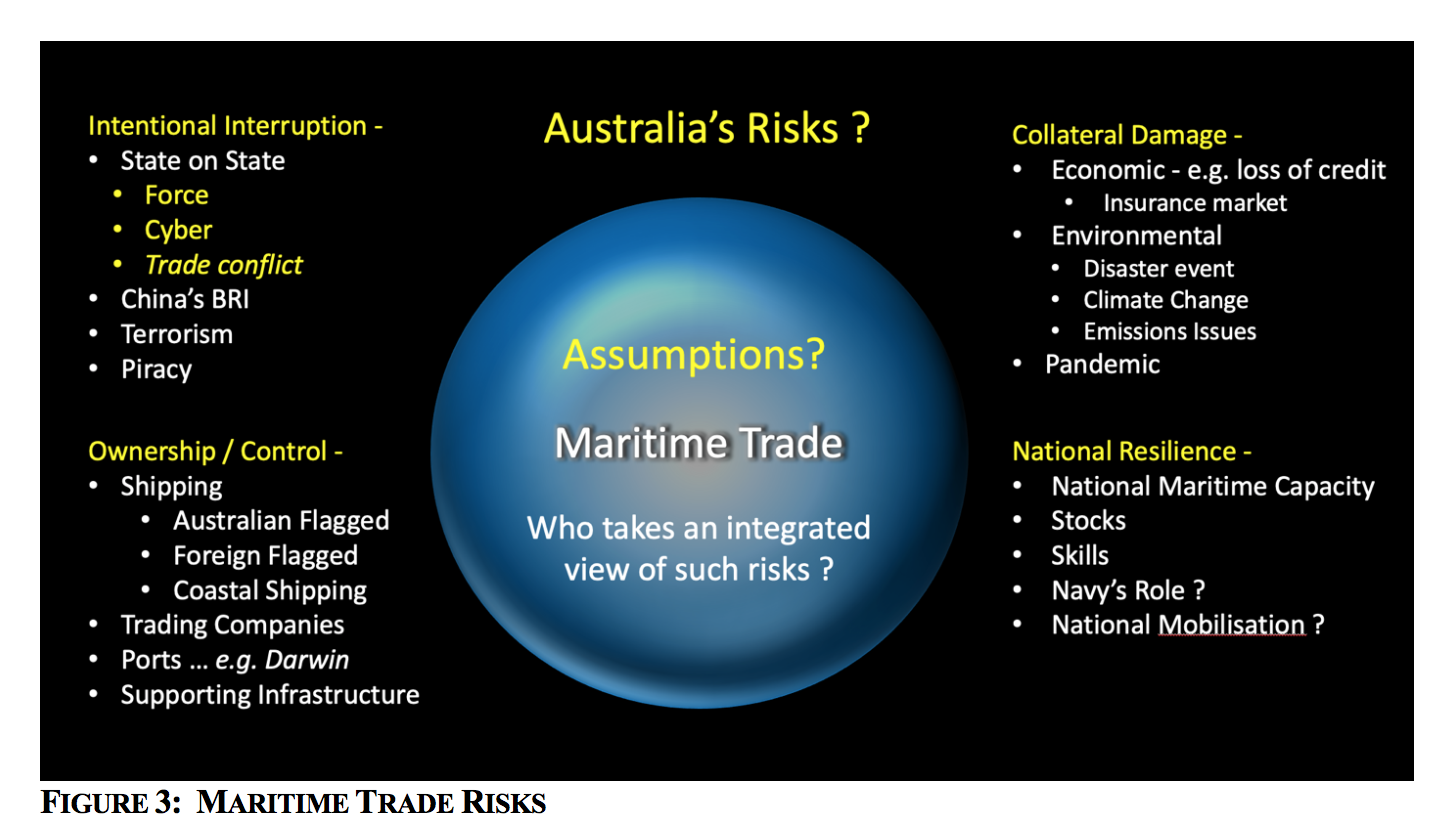

Figure 3 illustrates some of the issues that could be considered in such a risk assessment.

These include intentional interruption of trade, collateral damage from events such as an economic crisis leading to a failure of credit, natural disasters and climate change and pandemics. Issues such as the implications of ownership and/or control over shipping, trading companies, ports and supporting infrastructure also need to be assessed.

We also have to have a difficult conversation about our national resilience. What national maritime capability do we need such as a skilled workforce? What will be enough to maintain social cohesion during a disruption? What would be the role for the Australian Navy, albeit limited by its’ size? Can we actually mobilize as a nation? Given the decline in much of our industrial capability over the decades, and the large scale of reliance on, and outsourcing to, the market, it is highly unlikely.

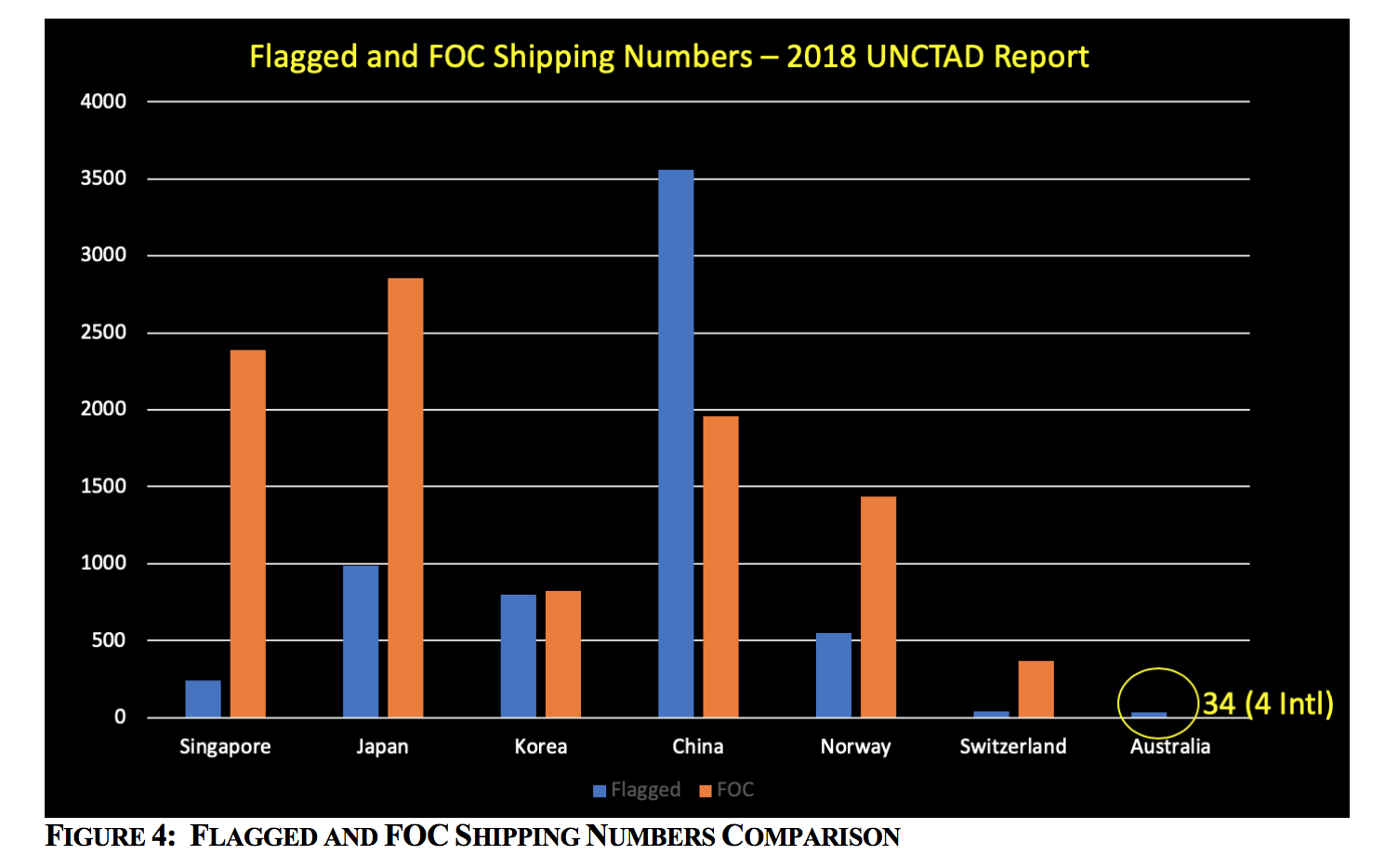

It is also interesting to compare Australian businesses approach to nationally flagged ships and to flag of convenience ships.

Figure 4 is a comparison of nationally flagged and flag of convenience vessels by country of ownership. With 34 flagged ships of 1000 tonnes or above, and with only 4 flagged ships capable of international trade (LNG tankers), Australian flagged shipping resources are minimal compared to most other countries.

As in the case of the comparison of mandated fuel stockholdings illustrated in Figure 1, it is perhaps worth asking why are we so different from most other countries, what do we know that makes us so confident to be so completely dependent on foreign owned/ controlled shipping for the arguably most important component of our national infrastructure?

The interconnectedness of the mechanisms that deliver the Australian way of life, increase our exposure to threats and disruptions.

There is no indication that an integrated risk assessment of our maritime trade vulnerabilities has been conducted.

Indeed, there is little evidence of the Government undertaking an integrated risk assessment of many of the economic, environmental and energy underpinnings of Australian society.

Over the last 10 – 15 years, there have been a number of Government-initiated reviews into aspects of maritime trade, but ultimately not much by way of meaningful action that would ensure resilience of our system of maritime trade within a framework of a national security strategy.

An Inquiry into Australia’s maritime strategy in June 2004 by the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade (JSCFADT), recommended that the Government to develop an all-encompassing national security strategy with ‘trade’ specifically mentioned.5

It took until 2013 for such a national security strategy to emerge under the leadership of Prime Minister Gillard.

Unfortunately, this strategy did not survive the subsequent change of government and nothing has been developed since.

To this day, Australia has no national security strategy or framework within which to understand and address the risks and resilience issues of such important things as maritime trade.

The same Inquiry by the JSCFADT also recommended that, ‘… the Government, as a matter of urgency, respond to the measures proposed by the Independent Review of Australian Shipping (IRAS), and state whether or not it intends to introduce an Australian Shipping policy.’ The Government indicated that it would not respond to the IRAS, and that, ‘the Government believes the best way it can support any industry is to maintain Australia’s strong domestic economy

In July 2017 the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport conducted an Inquiry into Increasing use of so-called Flag of Convenience Shipping in Australia and the Report was released. Recommendation Seven stated: ‘The Committee recommends that the Australian Government undertake a comprehensive whole-of-government review into the potential economic, security and environmental risks presented by flag of convenience vessels and foreign crews.’6

Such a recommendation seemed reasonable and indeed, a necessary process in order to understand the bigger picture issues around maritime trade and national security.

And one could be forgiven for assuming such a risk analysis has been undertaken.

The Government response to this recommendation in June 2018: ‘The Australian Government does not support this recommendation.’ One of the stated reasons for not supporting this recommendation was: ‘Given the multitude of reviews of different aspects of the maritime sector that have already been done conducted or are being currently progressed by the Government, as well as existing security and environmental protections in place, another review is not considered necessary.’7

It would appear that maritime trade, shipping and national security are topics for inquiries rather than topics to be addressed in a meaningful and holistic manner. And yes, there is yet another shipping review underway in 2019. The Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport inquiry entitled, Policy, regulatory, taxation, administrative and funding priorities for Australian shipping.8

This inquiry is due to report the findings by 5 December 2019.

The Terms of Reference for the inquiry address issues that have been explored at different points in time in many of the previous inquiries:

‘The policy, regulatory, taxation, administrative and funding priorities for Australian shipping, with particular reference to:

- new investment in Australian ships and building a maritime cluster in Australia;

- the establishment of an efficient and commercially-oriented coastal ship licensing system and foreign crew visa system;

- the interaction with other modes of freight transport, non-freight shipping and government shipping;

- maritime security, including fuel security and foreign ship and crew standards;

- environmental sustainability;

- workforce development and the seafarer training system;

- port infrastructure, port services and port fees and charges; and

- any related matters.’

It is noteworthy that ‘maritime security’ is identified as an issue for consideration.

Indeed, many of the submissions to the inquiry have made reference to the need for a ‘strategic fleet’ to give Australia resilience and genuine ‘maritime security’.

Unfortunately, in the rush for effectiveness, efficiencies and lowest cost, some submissions regard the discussion about a strategic fleet as interference with the market and something to be viewed with skepticism.

The Terms of Reference with respect to the interaction with other modes of freight transport, non-freight shipping and government shipping could be argued as already having been addressed.

In 2015, Infrastructure Australia identified the need for a national freight and supply chain strategy and the Australian Government agreed that such a strategy was necessary. Accordingly, in conjunction with the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Transport and Infrastructure Council, a strategy was developed.

The National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy and the supporting National Action Plan were released in August 2019 and provide an excellent starting point for understanding the complexities and interconnectedness of the freight transport system around Australia.9

There is detailed exploration of the current and future freight and supply chain challenges, and the risks and opportunities; however, the emphasis is primarily on the road and rail systems.

The National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy and National Action Plan are a missed opportunity for shipping and need not have been so.

During the investigations and analyses of the national freight task, a 15-page supporting paper on Maritime Freight

was prepared that highlighted the vital, increased, role that could be played by coastal shipping.10

Unfortunately, the Strategy discarded real consideration of coastal shipping because, ‘The focus of the Strategy is on our multiuser networks, such as our interstate road and rail systems and the aviation network, that carry some of our highest value freight. As they service a much wider user base, improving our multiuser networks can have significant flow on effects to the country as a whole.’11

This missed opportunity is not simply a ‘flagged ships or strategic fleet’ argument.

It is a missed opportunity to understand and integrate the shipping system into the national freight task as a whole.

The Need for a Maritime Trade Strategy

The Home Affair’s Profiling Australia’s Vulnerability Report referred to earlier in this article, provided conclusions, or perhaps more correctly threat assessments, worth thinking about in terms of maritime trade and maritime security.

It noted that our biggest vulnerabilities are the intersections and interdependencies in the systems that support us in this country from local to global levels.

As a nation we need to understand the consequences of past and present decisions that can have the perverse consequence of building in more vulnerability to us.

The blind trust in the market approach to governance, risk and resilience that has captured successive Australian Governments has, at the core, a drive to the lowest price. If we do not ask what that lowest cost really means to our national security, then we are have going to serious problems as a society. There is little evidence of any in-depth analysis of the national security implications of freight, shipping and the wider maritime trade system.

Maritime trade, and the complex and interconnected system that underpins it, is a national security issue. Returning to the question posed at the start of this article: has the Government has been as lax with the assessment of risks to our maritime trade as it has been with fuel security? I can only conclude that the answer is yes.

There is a need for an integrated maritime trade risk analysis, but where should the responsibility sit for undertaking such an analysis. There are a multitude of players: Navy, ship owners and operators, port managers, the unions, importers and exporters, and clearly, the Government, to name but a few.

The first question that should be asked is: What sovereign capabilities must Australia have in order to be resilient in this rapidly changing world?

The answer to this question goes to the military concept of ‘preparedness’. Would the Australian Defence Force go into combat without having trained, without being fully equipped, without understanding the mission, the enemy, and what the outcome was expected to be? This is preparedness. It is not fanciful, it is not esoteric, it is not an over-reaction to be prepared for eventualities. The world is a difficult, dynamic and increasingly dangerous ‘marketplace’.

Australia needs to be resilient to withstand interruptions and disruptions if, and when, they occur.

At a whole-of-nation level, the framework for our preparedness should be a National Security Strategy.

And at the heart of a National Security Strategy, should be a Maritime Trade Strategy.

Today, in Australia, neither exist.

How many wake up calls will we need?

Editor’s Note: This article and the next were presented in Blackburn’s paper to the Goldrick Seminar held last Fall.

Air Vice-Marshal John Blackburn (Retd) AO, MA, MDefStud, retired as the Deputy Chief of the RAAF in 2008. In a RAAF Reserve capacity, he subsequently supported the development of Plan Jericho, Plan Aurora and the analysis of IAMD options. He is now the Board Chair of the Institute for Integrated Economic Research (IIER) – Australia and a Fellow of the Royal Society of NSW, the Institute for Regional Security and the Sir Richard Williams Foundation.

See the first part of this article as well:

Footnotes

- Official Committee Hansard, Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee, Australia’s transport energy resilience and sustainability, 2 February 2015, page 19. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/commsen/e7c404f4-ef09-435b-8a52-dfb1c1af0746/toc_pdf/Rural%20and%20Regional%20Affairs%20and%20Transport%20References%20Committee_2015_02_02_3149_Official.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22committees/commsen/e7c404f4-ef09-435b-8a52-dfb1c1af0746/0000%22

- Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee Inquiry Australia’s Transport Energy Resilience and Sustainability Report, Recommendation 1, June 2015 https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Rural_and_Regional_Affairs_and_Transport/Transport_energy_resilience/Report/b01

- Advisory Report on the Security of Critical Infrastructure Bill 2017, Parliamentary Joint Committee on Security and Intelligence, March 2018, https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportjnt/024155/toc_pdf/AdvisoryreportontheSecurityofCriticalInfrastructureBill2017.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf

- Reported in Breaking Defense online news, 23 September 2019, NATO’s not ready for Saudi-style drone attacks; ‘It’s a serious problem’, author Paul McLeary https://breakingdefense.com/2019/09/natos-not-ready-for-saudi-style-drone-attacks-its-a-serious-problem/

- Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade, Maritime Security Report, June 2004, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House_of_Representatives_Committees?url=jfadt/maritime/report.htm#fullreport.

- Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee, Increasing Use of so-called Flag of Convenience Shipping in Australia Report, July 2017, Recommendations https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Rural_and_Regional_Affairs_and_Transport/FOCShipping45/Report/b01

- Australian Government Response to Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee, Increasing Use of so-called Flag of Convenience Shipping in Australia Report, June 2018 https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Rural_and_Regional_Affairs_and_Transport/FOCShipping45/Government_Response

- Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport, Inquiry into Policy regulatory, taxation, administrative and funding priorities for Australian shipping, Inquiry Home Pagehttps://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Rural_and_Regional_Affairs_and_Transport/Shipping

- Transport and Infrastructure Council, National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy, August 2019 https://www.freightaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-freight-and-supply-chain-strategy.pdf;

Transport and Infrastructure Council, National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy Action Plan, August 2019, https://www.freightaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-action-plan-august-2019.pdf

- Inquiry into National Freight and Supply Chain Priorities, Supporting Paper No. 2, Maritime Freight, March 2018 https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/transport/freight/freight-supply-chain-priorities/supporting-papers/files/Supporting_Paper_No2_Maritime.pdf

- National Freight and Supply Chain Strategy, August 2019, page 9