Looking Back and Looking Forward in Crisis Management: The Ukrainian Case

We published an article on July 29, 2014 which looked at ways the Ukrainian challenge might be addressed with innovations in how we would handle crisis management and military tools within a crisis management appraoch.

We argued that rather than looking into Putin’s soul and figuring out our next step in the Ukrainian crisis, it would be better to look carefully at the emergence of the next phase of 21st century warfare.

War is always with us; but it mutates over time.

In an age of globalization, total war is not a strategic objective of any major global power.

Having said that, what kind of warfare do the adversaries of the United States see as sensible to roll back American power and to reshape the globe in their image?

At the end of 20th century we learned that bringing down the World Trade Center was a desirable objective seen as part of the broader picture of the Middle East regional conflict. A similar effort was tried in France several years earlier, but was not recognized as such by analysts and policy makers. The World Trade Center attack was simply a copy cat plan of the aborted effort to strike the Eiffel Tower.

What we have seen recently in Ukraine with the Malaysian airliner is the next strike in this decade’s reinvention of warfare.

One could interpret this as an aberration requiring legal action, but this would miss the point of how it all started – the Russian seizure of Ukraine and the triggering the potential collapse of the Kiev government.

In a globally interconnected world, moves on one regional chessboard have consequences elsewhere, difficult to see at the time, but clearly happening nonetheless. 21st century warfare is about the use of hard power to gain advantage wrapped in the candy wrap of soft power. The best moves are those that can allow one to move ones pieces on the global chessboard without losing your pieces nor providing an excuse to your adversary to up the ante dramatically.

The isolation of world events as factually separate based on the variable of time or t is how the media and policy makers and many analysts interpret a particular event. The reality is that an event is always contextual, and that different actors operating in an event are working to shape an outcome to their advantage, the nature of which carries with it both past and future history.

When Putin seized Ukraine it was deliberate and seen as a relatively risk free opportunity to expand his energy empire and his place in the Mediterranean and the Middle East as well. It has been risk free from the standpoint of what the West has done in reaction, for this event has been isolated and almost forgotten prior to the jetliner being shot down over Ukraine.

The opportunity for the West to re-engage in Ukraine and to stop Russian map making in its tracks is clearly there; and not taking advantage of the crisis will have its own consequences upon key actors in the region and beyond.

It is not an in and of itself CNN moment; it is part of the texture of 21st century re-shaping of Europe and a contributor to the next chapter of writing the book on 21st century warfare.

The Attack on Ukraine as 21st Century Warfare

In a seminal piece on the Ukrainian crisis by a Latvian researcher, new ground has been laid to shape a clearer understanding of the evolving nature of 21st century military power.

Neither asymmetric nor convention, the Russians are shaping what this researcher calls a strategic communications policy to support strategic objectives and to do so with a tool set of various means, including skill useful of military power as the underwriter of the entire effort.

According to Janis Berzinš, the Russians have unleashed a new generation of warfare in Ukraine. The entire piece needs to be read carefully and its entirety, but the core analytical points about the Russian approach and the shaping a new variant of military operations for the 21st century can be seen from the excerpts taken from the piece below:

The Crimean campaign has been an impressive demonstration of strategic communication, one which shares many similarities with their intervention in South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2008, while at the same time being essentially different, since it reflects the operational realization of the new military guidelines to be implemented by 2020.

Its success can be measured by the fact that in just three weeks, and without a shot being fired, the morale of the Ukrainian military was broken and all of their 190 bases had surrendered. Instead of relying on a mass deployment of tanks and artillery, the Crimean campaign deployed less than 10,000 assault troops – mostly naval infantry, already stationed in Crimea, backed by a few battalions of airborne troops and Spetsnaz commandos – against 16,000 Ukrainian military personnel.

In addition, the heaviest vehicle used was the wheeled BTR-80 armored personal carrier. After blocking Ukrainian troops in their bases, the Russians started the second operational phase, consisting of psychological warfare, intimidation, bribery, and internet/media propaganda to undermine resistance, thus avoiding the use of firepower.

The operation was also characterized by the great discipline of the Russian troops, the display of new personnel equipment, body armor, and light wheeled armored vehicles. The result was a clear military victory on the battlefield by the operationalization of a well-orchestrated campaign of strategic communication, using clear political, psychological, and information strategies and the fully operationalization of what Russian military thinkers call “New Generation Warfare”…..

Thus, the Russian view of modern warfare is based on the idea that the main battlespace is the mind and, as a result, new-generation wars are to be dominated by information and psychological warfare, in order to achieve superiority in troops and weapons control, morally and psychologically depressing the enemy’s armed forces personnel and civil population.

The main objective is to reduce the necessity for deploying hard military power to the minimum necessary, making the opponent’s military and civil population support the attacker to the detriment of their own government and country.

By seizing Crimea, Russia set in motion internal pressures aided by direct support to continue map writing in Ukraine and to reduce the size of the territory under the country of the government in Kiev. The Crimean intervention was destabilizing, and the enhanced role of Russian “separatists” aided and abetted by Moscow within the remainder of Ukraine is part of the Russian 21st century approach to warfare.

The problem is that as the Russian’s shape a new approach, others are learning as well.

With a swift destruction of a Malaysian airliner by the use of a sophisticated surface to air missiles shot from Ukrainian territory, a new instrument of terror in the hands of those who wish to use it has been clearly demonstrated. And in the world of terrorists, imitation of success is a demonstrated way forward.

Putting the entire civil aviation industry at its feet is a distinct possibility. When terrorists slammed into the World Trade Center and stuck the Pentagon, the effect on the civil aviation industry was immediate. With ground missiles in the hands of terrorists the same dynamic can easily be unleashed.

Unfortunately, this might not be a one off event, even though the specific context is clearly unique. For example, the loss of thousands of manpads from the Odyssey Dawn intervention has been a lingering threat overhanging global aviation or evident in threats directly against the state of Israel. By conducting air strikes against Libya in March 2011, the stockpiles of manpads were not destroyed. The decision to NOT put boots on the ground to secure the KNOWN Libyan manpads stockpile, but to strike without any real consideration of the OBVIOUS consequences of thousands of manpads escaping destruction or control.

One or simultaneous manpad attacks against civil airliners are possible.

Much like slamming into the World Trade Center was a new chapter in warfare, this current Ukrainian development could be as well.

The proliferation from Libya to Egypt and Lebanon has already been reported. If a group associated with the former Libyan regime, based in Lebanon or Egypt sought to bring further focus on the crisis in Libya, attacking European airliners coming into Egypt would be plausible.

The initial reaction to such a manpad attack would clearly be to focus on the source of the attack. Intelligence sharing would be crucial to determine who and where the source of the threat lies. And there should be an immediate concern with copycat activities of other groups who might see an advantage from disrupting specific countries and to try to isolate them by using pressure to shut down airline based travel and commerce.

Within countries like Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and ISIS, there are distinct advantages by outsider groups to use such tactics to shape the political process. In the wake of such an attack, Europe and the United States and Asia would go back to planning underway when the Bush Administration was in power. The need to introduce defensive measures on airliners must be debated.

The threat of manpads now seen in terms of its more sophisticated brother has become a reality chilling the global aviation industry and providing a new chapter in the Russian-Ukrainian crisis

Which terrorists – whether state-sponsored, state-supplied or even worse able to gain access to lethal weapons and training to pop a civil airliner – remains to be determined, and that is an unacceptable strategic intelligence failure.

What Can the United States Do?

Simply asking Putin to man up and take responsibility is not going to get the job done. The United States needs to shape its own capabilities for 21st century warfare.

We could start by trying to actually engage in the information war which the Russians are conducting. Clearly, leveraging intelligence assets and putting the story into the Western press in DETAIL is crucial to position oneself for an effective information war engagement.

This is not about feeling good; it is about defeating the Russian information war gambit, which is holding the West responsible to trying to take advantage of the crisis for political advantage. We may feel privately that his position is less than credible; but it can be clearly believed worldwide.

But we need a hard power response to go with the diplomatic kabuki dance in which we are not engaged. And one clearly is at hand.

We argued in our book with Richard Weitz on Pacific strategy, that U.S. military power needed to be rebuilt around a modular, scalable force that could be effectively inserted in crisis. We also argued for the economy of force, that is one wants to design force packages appropriate the political objective.

If this was the pre-Osprey era, an insertion might be more difficult, but with the tiltrotar assault force called the USMC a force can be put in place rapidly to cordon off the area, and to be able to shape a credible global response to the disinformation campaign of Russia and its state-sponsored separatists. Working with the Ukrainians, an air cap would be established over the area of interest, and airpower coupled with the Marines on the ground, and forces loyal to Kiev could stop Putin in his tracks.

In other words, countering Russian 21st century warfare creativity is crucial for the United States to do right now with some creativity of our own.

Again it is about using military force in ways appropriate to the political mission.

Emerging Capabilities to Reinforce the Approach

The approach described here only gets better with the coming of the F-35 to US and allied forces. The multi-mission capabilities of the aircraft means that a small footprint can bring diversified lethality to the fight. An F-35 squadron can carry inherent within it an electronic attack force, a missile defense tracking capability, a mapping capability for the ground forces, ISR and C2 capabilities for the deployed force and do so in a compact deployment package.

In addition, an F-35 fleet can empower Air Defense Artillery (ADA), whether Aegis afloat or Patriots and THAAD Batteries, the concept of establishing air dominance is moving in a synergistic direction. An F-35 EW capability along with it’s AA and AG capability will introduce innovate tactics in the SEAD mission. Concurrently, the F-35 will empower U.S. and Allied ADA situational awareness. The current engagement of the IDF employment of their Irion Dome in conjunction with aviation attacks is a demonstration of this type of emerging partnership being forged in battle.

To get a similar capability today (as of 2014) into the Area of Interest would require a diversified and complex aerial fleet, whose very size would create a political statement, which one might really not want to make.

With an F-35 enabled ground insertion force, a smaller force with significant lethality and flexibility could be deployed until it is no longer needed for it is about air-enabled ground forces. A tiltrotar enabled assault force with top cover from a 360 degree operational F-35 fleet, whether USMC, USN, USAF or allied can allow for the kind of flexibility necessary for 21st century warfare and operational realities.

Lt. Col. Boniface in forecasting a “tsunami of change” to come, understood without even saying so the evolving nature of warfare, and in this case was talking about the Osprey and the coming of the F-35B:

I sort of think of it like a game of chess….. If you have ever played chess it sometimes take a while to engage your opponent.

We now have the ability to move a knight, bishop, or rook off of this same chessboard and attack 180 degrees towards the rear of our enemy.

We can go directly after the king.

Yes, it’s not really fair, but I like that fact.

Our politicians and strategists need to understand the changing nature of warfare and how to engage our assets for strategic advantage.

Our adversaries are certainly not waiting around for Washington to get smarter.

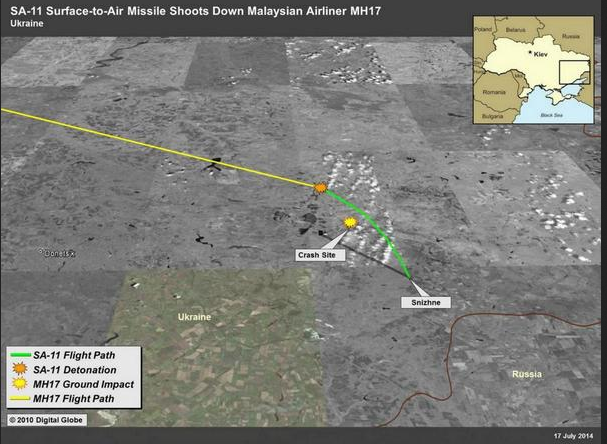

The featured graphic shows the path of the SA-11 shoot down of the Malaysian Airliner MH-17 over Ukrainian territory.