Remembering Massoud in the Endless War

The endless war goes on in Afghanistan with no clear strategy or policy in place to end the American engagement.

If the Pentagon strategy on dealing with peer competitors is to be realized, resources need to be mobilized to deal with this evolving threat and set of challenges.

Assumptions made about the endless capacity of the US and its allies to sink investments into a commitment to fitting land wars of the type which have little or no real relevance to dealing with the Chinese or the Russians have proven invalid.

We need to put the land wars behind us and get on with the strategic shift.

The following article which we published SEVEN years ago called for a recognition that the endless war well needed to end from the standpoint of the costly engagement needed to be terminated.

Stability operations really have very little to do with success against a peer competitor and the skill sets and equipment and investments in the first have little carry over to the second, and actually create a significant learning problem to move from the first to the second.

What follows i the article published on September 14, 2011 entitled Remembering Massoud:

As Americans observe the day 10 years ago when terrorists in hijacked planes attacked New York and the Pentagon, the people of northern Afghanistan remember what for them was a greater tragedy two days earlier on Sept. 9, 2001. It was then that two agents of Al Qaeda posing as journalists detonated a bomb hidden in a television camera during an interview with Mr. Massoud, killing him instantly.

For his closest aides, who first tried to keep his death secret, fearing the truth would sink the besieged Northern Alliance for good, the collapse of the World Trade Center towers was a sign of hope. They instinctively saw a nexus in the two acts — though one has never been proved — and knew that the Americans would soon be on their way.

“I sort of woke up out of this shock I had been in since Sept. 9,” Abdullah Abdullah, the Northern Alliance’s former foreign minister, recalled about hearing the news of the attacks in New York. “It automatically came to my mind that out of this tragedy, there might be an opening.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/11/world/asia/11massoud.html?ref=todayspaper&pagewanted=print

Earlier we had an opportunity to discuss with Johan Feckhaus, a former French military officer and an advisor of Massoud about the way ahead in Afghanistan.

In our interviews with Freckhaus he connects two broad points.

First, the light footprint followed by the Bush Administration after 9/11 was the right strategy. The piling on of foreign troops has stirred up a hornets nest of Taliban activity who are using the large scale foreign presence as a recruiting issue. The point simply put is that Afghans distrust foreign motives and the large number of troops.

And the foreign troops are backing a centralized government, which is out of sync of broader Afghan national aspirations and objectives. Certainly, recent events in the Middle East suggest that building up the power of the Presidency, as a focus of Western activity might well be counterproductive for political progress. In a recent speech to the Kuwait National Assembly, on 22 February 2011, the UK Prime Minister admitted: “For decades, some have argued that stability required highly controlling regimes (…). [We] faced a choice between our interests and our values. And to be honest, we should acknowledge that sometimes we have made such calculations in the past. But I say that is a false choice.”

Johan Freckhaus also suggested an interesting lesson from history that might just work — a Swiss “neutrality” model from the time of Napoleon. His observations in his own words are extremely interesting. The West can work with Russia, Pakistan and others to shape a neutrality treaty and can assist where appropriate in countering foreign fighters like Al Qaeda and the Taliban seeking to penetrate Afghan territory. But the West needs to leave security to the provinces, and work with a much smaller central government tasked with dispensing aid to the provinces, control of the Army and collecting taxes. But the provinces cannot, nor need, manage large police forces.

In the earlier interview, Olivier underscored the following remarks by Johan:

There is indeed an insurgency in Afghanistan because you have 30 000 or 40 000 rebel fighters – according to allied military intelligence – backed by millions of Afghan civilians, in growing numbers, who feed them, house them, transport them, protect them, give them information and so on. These civilians are doing it foremost to drive foreign troops out of the country and in rejection of the system we are trying to impose, but do not want the return to power of the mullahs either.

Withdrawing our troops is therefore the right strategy to effectively drive a wedge between the rebels and their supporters. This famous momentum, this magic moment where the power relationship can be reversed, will come from fair and complete withdrawal of foreign forces, because then the fate of the country will return to its population. Then the Afghan security forces, as they exist today, would very well be capable, with the help of villagers, of chasing away those rebels on motorcycles mainly armed with Kalashnikovs and rocket launchers, whose most lethal know-how is simply to trigger explosives remotely.

The strategy of “always more” prevalent until today for the Afghan security forces is a dangerous illusion: more troops, more money, more power to the central government, all of this is counter-productive, it fuels the insurgency! We are building oversized security forces in Afghanistan that the country is far from being able to afford. We imagine a police state, supported from abroad, which would subject the population to the decisions of Kabul.

We imagine building in a few years, for one of the poorest countries in the world, an army that could successfully maintain in power a hyper-centralized system. This is not sustainable.” Let’s remember, for the record, that the Afghan government, which now has 140, 000 military and 109, 000 police officers, aims at a 240,000 military and 240,000 police officers force. And that is for a country of about 20 million inhabitants. In comparison, France, for a population three times larger, has fewer than 170,000 military personnel (ground and air) and 265 000 gendarmes and police officers.

http://www.sldinfo.com/rethinking-the-afghan-engagement/

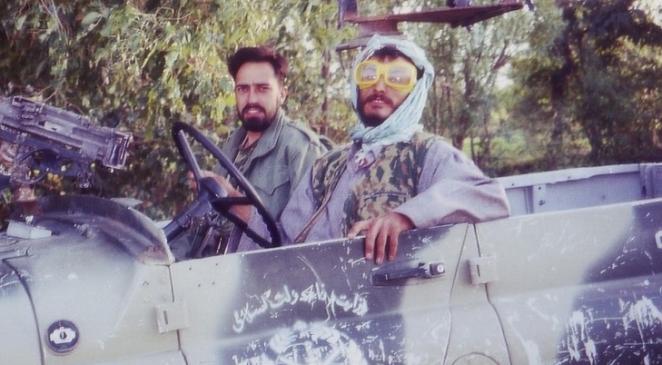

The featured photo shows Johan Freckhaus in Afghan operations with Masoud.