Transformation and Ongoing Combat Innovation: The Key Role of the 0-5 Year Reshaping of the Combat Force

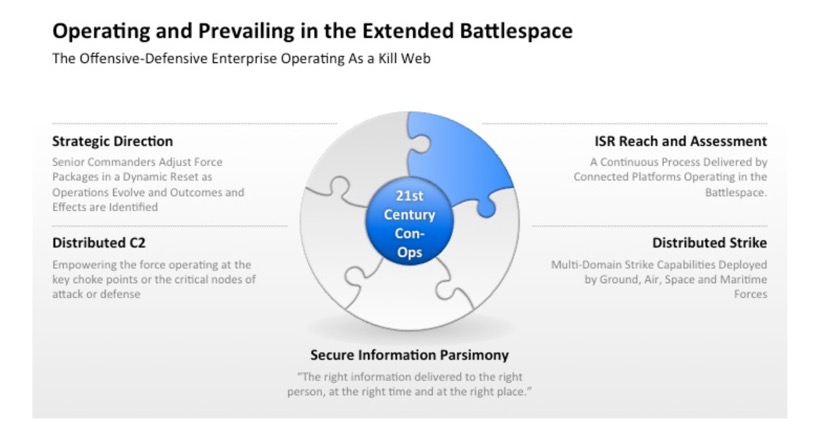

One of the key features of our approach to military transformation was and continues to be how to leverage the new systems we are already bringing on line which allows us to expand our deterrence in depth capabilities.

There is way too much emphasis Inside the Beltway on potential and hypothetical future systems and significant denigration of how the newly being introduced systems when much more effectively integrated with robust C2 rather than some hegemonic Amazon cloud like system can deliver the capabilities we need in the evolving five year period in front of our forces.

It too often seems that the approach is shaping dense briefings of the world in 2030 as a deterrent to our adversaries rather than building out the capabilities, which are within reach as new systems enter the force.

Although interesting to speculate about technology and the future of warfare, the core point is the future is now. The US and its allies have to be ready in the near to mid term to deal with 21stcentury adversaries who will use a variety of crisis management and warfighting tools to advance their interests.

This means leveraging the force we are evolving now to reshape effective concepts of operations to prevail now.

Such an approach is reinforced as we introduce software upgradeable systems as the core platforms for our combat force. And such a change also calls for reshaping the business rules, which drive acquisition as well.

As Brian Morra put it in an article published in 2017:

The digital nature of new weapon systems like the F-35 makes multi-phased development and multi-modal budgeting feasible.

This approach bears some similarity to the spiral-development approaches used in the past.

However, a new approach will need to be qualitatively different than traditional spiral development.

The ability to upgrade new weapon systems primarily through software upgrades makes this new approach possible.

The new approach would have shorter upgrade cycles or modes, based on 3-5 year centers.

Budget planning will need to change since each new “mode” would blend acquisition and O&S monies. Each new mode would require a business case to support decisions to deploy funds.

This is a very different approach.

It would require different business rules and procedures than are currently employed by the DoD’s acquisition centers.

The obstacles to this kind of reform are not technical, although some will assert that technical issues are insurmountable. The real obstacles are DoD’s current business rules and acquisition policies and budgeting procedures.

The question is will we reform these procedures now, or will we only do so when we are confronted with a crisis?

The US aerospace and defense industry maintains proprietary control over its core capabilities.

This is a key challenge that DoD confronts that China (in the main) does not. In order to have affordable, multi-modal weapons system development, DoD will have to establish new business rules to enable proprietary sharing or compartmentation schemes that create the conditions for development across proprietary stove pipes.

The need is clear.

The DoD requires business rules appropriate for high-intensity acquisition to meet the rapidly evolving threats represented principally by China and Russia.

The growing importance of cyber and digitally-enabled systems means that DoD can no longer operate with industrial-age procurement and sustainment rules.

Fortunately, the transition to digital systems lend themselves to a new, multi-modal approach that will help the United States keep pace with evolving threats.

And in a recent piece by Michael Shoebridge, director of the defence, strategy and national security program at ASPI, he argued that such an approach was crucial to Australian capability development as well.

In his piece. he highlighted the role which the Australian government was adopting with regard to Australian Special Forces and argued that the core principle being adopted for acquisition in this area could be generalized throughout the defense structure, very much along the lines which we have been arguing as well.

The $500 million announced by the Morrison government to be spent over four years to keep Australia’s special forces’ capabilities at the global leading edge as part of a $3 billion, 20-year program isn’t new news in one way—it was announced in the 2016 defence white paper—but it’s big news in another.

‘Project Greyfin’ is a stark recognition of the need to keep up with rapid technological change and to make rolling investments to do so, rather than one-off big-bang spends every 10 or 15 years, as has been common practice for capability investments for some decades now.

What’s different about Project Greyfin is that (despite its name) it’s a long-term program, not the normal big defence project. That may sound like language games, but it’s about a different concept for investment. It’s an approach that’s based on the understanding that specifying in 2019 what special forces will need in the 2030s is probably a mug’s game. The rate of change in what’s possible—and therefore in what’s needed—is enormous.

A few examples show what this looks like. We know about trends in defence innovation, but the specifics aren’t clear enough to enable Defence to buy or sign a contract right now. By 2030, new materials for vehicles and clothing may allow masking of the heat signatures and other signals that can be spotted and used to target people and machines. New battery types will allow energy storage to power advanced electronics carried by soldiers and various autonomous vehicles that help special forces operate remotely for long periods of time.

Advances in smart munitions—what we used to think of as bullets—will probably look more like guided rounds that are almost as intelligent as current missiles, with seekers and sensors that allow them to find and guide themselves to targets. And autonomous drones will proliferate, as will the kinds of things they can do to help special forces remain undetected, collect the intelligence they need, and protect themselves from adversaries.

So, we know that designing the detail now about what special forces will need to have in the 2030s won’t work. Encouragingly, though, the government’s path is taking this into account. The plan seems to be to let special forces folk do a mix of buying now what is available and at the leading edge of fielded capability and also investing in concept and demonstrator activities that help define what will be acquired in the next four-year phase of Greyfin. That should allow both Defence and industry to develop long-term partnerships and development programs with the confidence that the money will be there when the right equipment is mature.

Special forces are probably the most trusted to deliver value for money on investment across Australia’s national security community. They can be expected to experiment wisely and for clear operational purposes.

Nevertheless, the broad government procurement system that even the special forces can’t escape probably needs to change to allow the real promise of this new approach to work. A total of $500 million over four years is still a significant amount of taxpayer money, so there’ll be a temptation in places like the Department of Finance—and even among Defence’s internal finance and procurement staff—to inflict the same heavy-handed procurement processes on Greyfin as on much larger major systems programs like frigates and submarines.

That would be a mistake, because it would work against the entire purpose of this new type of investment program—which is about being able to match our military’s speed of adoption of technology to the speed of change in the technological environment.

The goal for those overseeing Greyfin needs to be to show how they can accommodate this new approach within the Commonwealth’s broad procurement principles and keep it moving at speed.

Some project management risk needs to be accepted in exchange for reducing the risk that our militaries—or our intelligence agencies—will be outmatched by better equipped adversaries whose governments let them experiment and adopt the successful results. It’s about realising that minimising the project management risk just shifts the risk to the capability outcomes—and so to our soldiers in the field.

At the same time, special forces are in good company in needing to find a way to introduce new technologies rapidly and continually. The rest of Australia’s national security community—whether the big Defence organisation, Home Affairs, or Australia’s intelligence agencies—face this same defining problem.

Even the largest, slowest-moving capability programs—like the future submarine—need better ways of balancing capability risk with project risk in this new environment. It’s critical to spread the more agile Greyfin approach to them, and to have central agencies and Commonwealth procurement staff help with this by rethinking their processes to accommodate this new approach.

That will take a new type of oversight and project management that is not designed around engineering-age mindsets and processes. It may even take setting up a separate capability development process, with its own purpose-built oversight arrangements, rather than trying to make the existing one—designed to deal with big platform acquisitions during times of relatively stable technology—run faster.

Because the special forces are, well, special they have often been allowed to bypass slower project development and acquisition routes because the government wants to make sure they’re ready to be deployed at very short notice and have the best equipment on hand. Some of that sense of urgency should now be applied to how Defence, and Australia’s broader national security community, updates its kit with new technology if we are to retain capability advantages.

Special forces have often been the innovation leaders for the broader Australian Army. Now they need to be pathfinders for Australia’s national security community in another way—establishing how procurement principles and practice can change to shift the risk approach from one concentrated on reducing project risks to one that’s more focused on limiting capability risks by embracing more rapid technological change.

Our future special forces soldiers and future members of every national security agency will benefit, as will Australia’s security.