Defending South of Australia’s ‘First Island Chain’

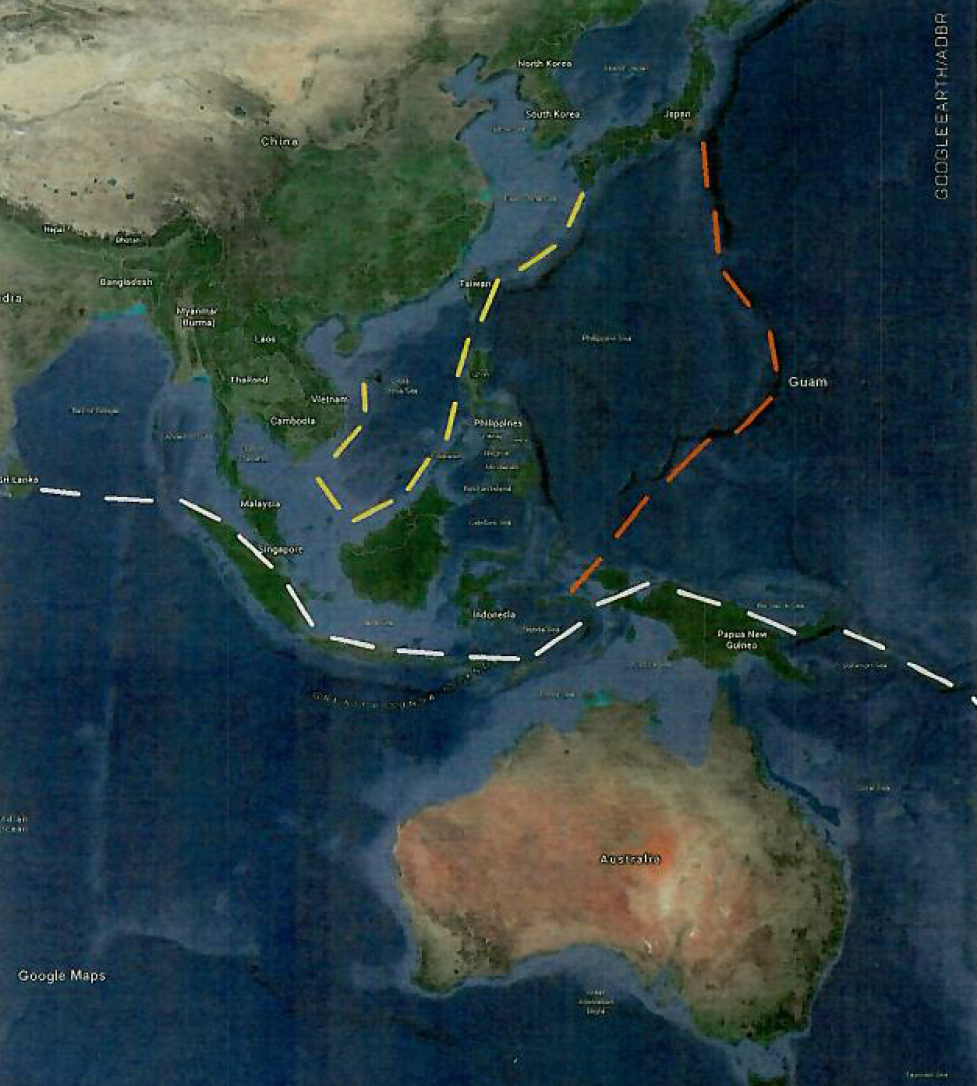

A continuing theme in Chinese strategic thinking is the concept of “island chains” with the First Island Chain stretching from the Kuril Islands of Southern Japan, through the Northern archipelago of the Philippines, to northern Borneo.

A Second Island Chain extending through the Marianas, including Guam, lies beyond the First Island Chain with a Third Island Chain in the central Pacific. Of these three chains it is the First Island Chain ‒ which includes Taiwan ‒ that is of prime economic, strategic, military and geo-political significance to China.

With many archipelagos lying to the north of Australia, the concept of island chains might also have application to Australian strategic thinking. Certainly, the first Chief of the Air Staff of the RAAF, Sir Richard Williams, showed keen interest in the archipelagos to the north of Australia and, in 1926, he conducted an extensive familiarisation flight up the east coast of Australia, through Papua, New Guinea and on to Tulagi in the Solomon Islands.

Williams departed Point Cook on 25 September 1926 in a de Havilland DH50, a civilianised version of the DH9 bomber with an enclosed cabin for four passengers, with the pilot seated in an open cockpit at the rear of the cabin. The biplane, powered by a single Siddeley Puma water-cooled engine, was fitted with metal floats. On the flight, Williams was accompanied by Flight Lieutenant McIntyre, pilot and Corporal Trist, mechanic.

The DH50 returned to Point Cook on 7 December, having flown some 10,000 miles, visited 23 localities outside of mainland Australia, and logged 126 flight hours ‒ an aviation feat not only of considerable historical significance to Australia but also, a flight of great value to Williams in his role as Chief of the Air Staff.

More significantly, Williams’ ten weeks in a DH50 floatplane was further evidence that he had already turned his mind to the implications of the disposition of the archipelagos to the north of Australia, in how to defend Australia from emerging threats. The flight was a pragmatic way of investigating how the evolving capabilities of the aeroplane could exploit the archipelagic disposition to the betterment of Australia’s defence.

Today, and given the recent surge in Australia’s interest in its South Pacific neighbours, is the concept of “island chains” of relevance to Australian strategic thought?

Certainly, the geography of the archipelagos remains unchanged although a new strategic and geo-political framework has evolved, having replaced the sub-servient colonies of former colonial powers.

But also, Australia’s regional interests are now Indo-Pacific in nature; hence, a twenty-first century concept of “Australia’s First Island Chain” should be more appropriately defined as stretching from Sri Lanka; along the Indonesian archipelago from Sumatra and Java to Irian Jaya; through Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands; and on to Vanuatu and Fiji.

From a strategic perspective, that extensive region from mainland Australia and its island territories to the southern shores of “Australia’s First Island Chain” might be described, in academe strategic terms, as “Australia’s Sphere of Influence”. Or, from a national security perspective the region might be described, in pragmatic sporting terms, as “Australia’s Red Zone”, with the consequential theatre of military operations being predominantly maritime.

Significantly, military operations within this area play to Australia’s strengths of high levels of professional military mastery and an aptitude for the exploitation of technologically advanced capabilities; with Australia’s continuing investment in surveillance, reconnaissance, information and intelligence capabilities key to the successful conduct of sub-surface, surface and above-surface maritime operations.

So, although this theatre of operations is vast ‒ and provided government continues to grow defence funding to 2% of GDP ‒ and then a little more to fund some capability augmentation, Australia’s defence forces can be expected to operate with military credibility throughout this “Red Zone”.

On the other hand, operations into and beyond Australia’s First Island Chain will involve other nation states and their sovereign territories. They also come with difficult island and littoral geography and, almost certainly, will require access to forward basing and will need to be undertaken with the support of allies ‒ together with a Pandora’s box of strategic, geo-political and operational scenarios which complicate and hinder both conceptual force structure planning and operational contingency planning.

In contrast, the notion of Australia’s First Island Chain brings a clearer conceptual basis for force development and operational planning, a lesser dependence on the complexities and national interests of partners and allies and yet, the region remains of critical relevance to Australia’s security.

So, is Australia capitalising on these realities by devoting enough effort to the detail of how Australia can defend and dominate the nation’s “Red Zone”?

Part Two

Military operations south of Australia’s First Island Chain could credibly be sustained and conducted from Australia and executed under Australian national command – unlike operations beyond Australia’s First Island Chain which would involve access to forward basing, the concurrence and support of allies and neighbours, and difficult operational scenarios.

This theatre also would assume elevated national security importance to Australia should global issues cause levels of political, strategic, military and logistic support from the US to fall short of Australian expectations. This is not an unreasonable assumption given US commitments in the Indo-Pacific, especially to Japan and South Korea.

The US also might find itself pressured on other fronts, particularly by Russia which is seeking to advance its territorial ambitions. All this, without even factoring in the complications of US commitments to the Middle East

So, although not by desire but necessity, Australia might find itself almost wholly responsible for the defence of its island continent, its approaches, its national interests, and of Australian (and US) logistics and enabling bases. But there are some positives in facing this security challenge.

First, operations south of Australia’s First Island Chain play more to Australia’s advantage than to an enemy which would be required to sustain challenging military operations at long distance from home bases.

Second, Australian military operations, especially maritime, play to Australia’s high levels of professional military mastery and the nation’s aptitude for the exploitation of technologically advanced capabilities. This is particularly the case with ISR and with information and intelligence, which will hopefully be assisted by continued support from off-board coalition capabilities.

The ability to operate with situational awareness and to target accurately at long ranges while denying an enemy that capability will be key to favourable operational and tactical outcomes in the maritime domains. These factors, together with the ability to conduct credible, long-range operations from Australian bases in a familiar environment, add to what should be a significant ‘home ground advantage’.

So how does Australia’s force structure shape up to the challenge of operating against an adversary seeking to venture into Australia’s vast front yard?

The answer is not immediately obvious from Australia’s Defence White Papers which are expressed in abstract terms such as: decision-making superiority; enabled, mobile and sustainable forces; and capability streams, etc. For example, the 2016 Integrated Investment Program (IIP) recommends the acquisition of both seven Triton maritime UAS and 15 Poseidon manned aircraft, with no reference that these two systems are essentially complementary with a combined effectiveness considerably greater than the sum of the two individual systems.

More critically, the IIP makes no mention of whether these two capabilities provide an operational capability in only one area of operations, or are sufficient to conduct operations simultaneously in two areas. This is fundamental to any assessment of the strength and preparedness of the ADF’s capability.

This should not be taken as criticism of past Australian force structure policy when it was – in more benign times – probably the best basis on which to plan a national defence capability. But the world has changed. Long-standing rules-based international processes have been disregarded, propaganda and proxies are being used as vehicles to advance nation states’ interests, and nation state militarisation is escalating.

In this environment, Australia now needs to assess more critically just how well its planned defence capabilities can cope with emerging threats. A good start would be to assess how well Australia’s IIP military capabilities can deter, neutralise and, if necessary, defeat assertive foreign military action in the expansive theatre south of Australia’s First Island Chain….

Without downplaying the importance of the Australia-US alliance, global issues might dictate that anticipated levels of US military and logistic support fall short of Australian expectations ‒ a not unreasonable assumption given the commitments the US has in the Indo-Pacific (Japan, South Korea and Taiwan), in Europe (especially in Eastern Europe and the Baltic), in South Central Europe and the Black Sea, and in the Middle East.

Across the globe the US ‒ facing a militarised China under the rule of an autocratic, nationalistic, aggressive and belligerent Communist Party of China ‒ might be forced to focus its limited Indo-Pacific military resources on matching China’s capabilities, especially air and naval, from established US bases in Japan, South Korea and the Central Pacific. That could lead to the US leadership ‘delegating’ to Australia, the conduct of all military operations south of Australia’s First Island Chain.

Part Three

Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities are the foundation of national security. But in the past, Australian defence policies have used ISR in the strategic context of ‘Warning Time’ rather than in an operational or tactical context. In this strategic context, the role of ISR is to warn of the emergence of threats as they emerge so that they are recognised and responded to by a corresponding upgrade in national defence capability.

Today, there seems little doubt Australia is in Warning Time. Indeed, that realisation appears to have come a little late with some 2016 IIP defence capabilities not scheduled to begin to appear until the mid-2030s. Capabilities that will not begin to materialise until the mid-2030s and later, will be of little use in 2025.

Fortunately, many of the ISR capabilities that Australia has prioritised also have immense value in an operational theatre. These include the acquisition of six MQ-4C Triton unmanned surveillance systems and 12 P-8A Poseidon manned aircraft, both recommended in the 2016 IIP.

The IIP also foreshadowed an increase to 15 P-8A, which at a mission availability rate of 75%, translates into 11.25 “mission-available” P-8A. The MQ-4C and P-8A capabilities are complementary, and when combined with the four long-range electronic warfare support aircraft based on the Gulfstream G550, the Jindalee OTH Radar Network (JORN), and coalition Australia-US ISR capabilities, Australia will possess a modest but impressive operational ISR capability.

But is this ISR capability enough to sustain ongoing operations out to Australia’s First Island Chain?

And, is it possible for these ISR capabilities to sustain ongoing operations, simultaneously, in two areas of operations such as in the North Coral Sea and off the North West Shelf?

Noting the US Navy allocates five MQ-4C to an operational node from which to sustain 24/7 ISR operations, the Australia MQ-4C capability will support only one node of 24/7 unmanned ISR operations. Whether this is adequate is debatable given long-range ISR operations are asset intensive as illustrated by the heavy AP-3C commitment in the mid-1990s search and rescue operations for round-the-world yacht racers; their heavy tasking in operations against illegal Patagonian Toothfish fishing boats; and in the search for MH370.

So, getting the MQ-4C and P-8A operational fleet sizing right and balanced, will be critical to the efficiency and effectiveness of the operational ISR capability.

But one positive from the introduction of the unmanned MQ-4C is that it relieves the manned P-8A of most of the long duration and repetitious surveillance activity, freeing the P-8A armed with mines, torpedoes and anti-ship missiles (ASM) to focus on the anti-submarine and anti-surface roles. Given the changing maritime power balance in the Indo-Pacific, this refocus of P-8A operations is timely and, arguably, provides justification for the early acquisition of the three additional P-8A foreshadowed in the IIP.

The changing maritime power balance in the Indo-Pacific has also stimulated the development of new, technologically advanced, US ASM capabilities (noting recent US reports of a possible Foreign Military Sale of AGM-158C LRASM to Australia for carriage on F/A-18F Super Hornet). And with the AGM-158C likely to be cleared for carriage by the P-8A in the mid-2020s, there is a strong case to arm RAAF P-8As with the AGM-158C.

With both the P-8A and F/A-18F armed with the stealthy, heavyweight, sophisticated and long-range AGM-158C, the ADF will possess a strong deterrent to threatening foreign naval incursions south of Australia’s First Island Chain.

Air dominance is the prime role of the F-35A, although the in-theatre distances will make F-35A operations generally reliant on AAR support. The F-35A with its stealth, AIM-120D AMRAAM, long-range targeting ability and networked operations is a potent air dominance capability. As 2025 approaches, the operational capabilities of the F-35A will be further enhanced by the Block 4 upgrades which, apart from system and weapons upgrades, could include the integration of the Joint Strike Missile (JSM) or another ASM, and the possible integration of the follow-on AIM-260 JATM long-range air-to-air missile.

The air force operates six E-7A Wedgetail, Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C) aircraft; a world class, critical enabling capability for both air and naval operations. But a fleet of six aircraft translates into only 4.5 mission-available E-7A. But while the 2016 IIP includes a significant upgrade to the AEW&C systems, it’s failure to increase the AEW&C fleet to eight aircraft (which would provide six mission-available E7-A) leaves the ADF deficient in the key operational and tactical co-ordination and control nodes, critical to mission success.

The E-7A is also reliant on AAR support. A mission of about 10 hours, for a task at 1,500 km distance, involves five hours in transit and five hours on-station. Therefore, to sustain a 24/7 on-station E-7A presence, 4.8 missions must be tasked ‒ not achievable from the current fleet of six aircraft.

But E-7A on-station time can be achieved with AAR support. By increasing mission duration to 15 hours, which also increases E-7A on-station time to 10 hours, AAR realises a 100% increase in E-7A on-station time. With AAR support, only 2.4 missions are needed to sustain a 24/7 on-station E-7A presence. This example also demonstrates that enabling AAR generally flows ‘straight to the bottom line’ of increased on-station presence. AAR support confers similar dramatic increases in on-station presence to the P-8A, EA-18G, F/A-18F and F-35A.

The 2016 IIP expanded the MRTT capability to seven aircraft and foreshadowed a further increase to two aircraft, nominally to support P-8A operations. But even a fleet of nine MRTT aircraft ‒ with 6.75 mission-available MRTT ‒ is insufficient to provide the necessary AAR enabling capability to conduct credible air operations, at task force level, in our region. In short, this deficiency in AAR support puts at risk the operational effectiveness of an otherwise potent Australian air combat and sea denial capability upon which successful Australian air and naval operations must be based.

In conclusion, the 2016 IIP has provided a framework of complimentary air capabilities that, in 2025, and with some augmentation, will pose a formidable challenge to any hostile air and naval incursion south of Australia’s First Island Chain.

But the IIP has not recognised the criticality of the E-7A AEW&C capability to successful air and naval operations in the theatre, and of the necessity of increasing enabling AAR capability to support the range of likely concurrent air and naval activities.

Brian Weston is a Board Member of the Sir Richard Williams Foundation. He served tours in Defence’s Force Development Analysis Division and the HQADF Force Structure Development Planning Branch.

This article was published in three parts, and has been combined by defense.info into a single article.

https://www.williamsfoundation.org.au/post/copy-of-australia-s-first-island-chain-part-1

https://www.williamsfoundation.org.au/post/australia-s-first-island-chain-part-2

In the graphic above, Weston highlighted both China’s first island chain (seen in the yellow markings) and Australia’s first island chain (seen in the white).

The red zone indicated covers what I would consider the joint expanded Japanese perimeter and the strategic triangle for operating U.S. forces for power projection in the region.

From the red and white dotted lines are what we would consider to be the strategic quadrangle, which is discussed later in the article.

Also, see the following: