The Direct Defense of Australia: Looking Back and Looking Forward

Both of my initial interviews during the current visit to Australia have highlighted the need to shift from an ADF prepared for the away game in support of global engagements and American strategy to a priority upon working the regional defense perimeter of Australia.

If one looks back to the work of Paul Dibb in the 1980s, he highlighted what he saw as the priority for the defense of Australia defined in geographical terms.

In an article by Peter J. Rimmer and R. Gerard Ward focused on Dibb’s DOA model, this is how they described his approach:

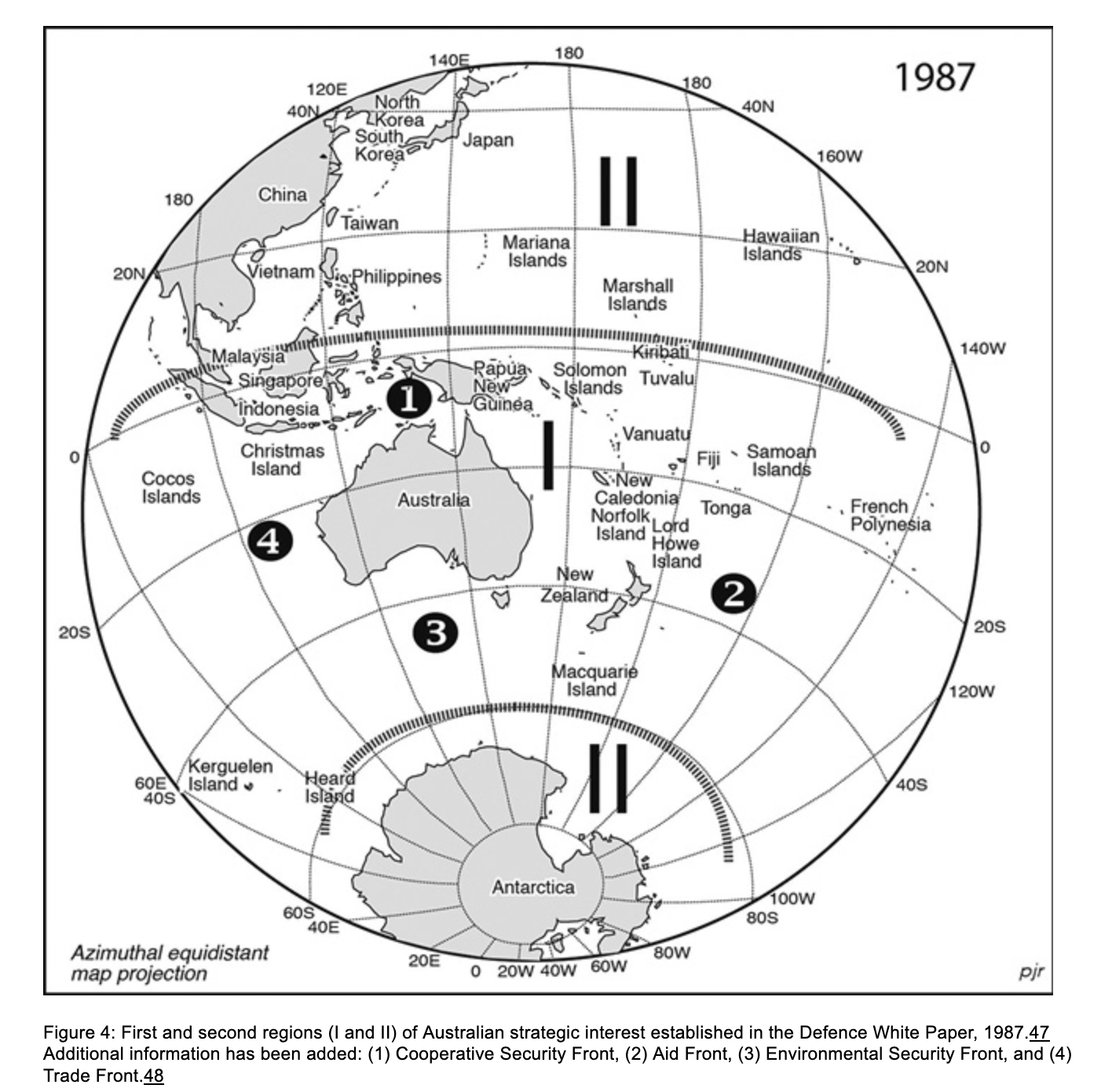

Dibb’s conceptual base for the DOA paradigm, prioritising air and naval forces to defend the sea–air gap north of Australia, took its cue from Sir Arthur Tange’s astute observation that ‘a map of one’s own country is the most fundamental of all defence documentation’.46 Given Australia was a ‘middle ranking power’ with modest defence resources, Dibb proposed a layered geographical construct to guide defence planning.

- An area of direct military interest, accounting for 10 per cent of the globe, where attention should be concentrated upon securing the country from attack by another state by having a military technological advantage to defend the country’s northern air and sea approaches through island or archipelagic states, and the inner arc of countries from or through which a threat could be mounted.

- A broader area of primary strategic interest, covering 25 per cent of the globe from the mid-Indian Ocean in the west to the mid-Pacific in the east and from South-East Asia and the China Sea in the north to Antarctica in the south.

- The rest of the world that afforded opportunities for coalitions but was not a primary determinant of force structure.

This concentric-ring model was designed to provide Australia’s defence strategists with an ironclad discipline to shape strategy and force structure; it also provided a construct to distinguish between ‘wars-of-necessity’ and ‘wars-of-choice’ (i.e. the difference between interventions in the Solomon Islands and East Timor versus Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan).

This constitutes the looking back piece of highlighting a way ahead for the direct defense of Australia, but fortunately Dibb has provided updates himself to his earlier work in more recent pieces.

In a 2019 article, Paul Dibb noted the new strategic situation facing Australia and the return of the key importance of geography.

“We now come to today’s deteriorating strategic environment for Australia. As Richard Brabin-Smith and I argued in Australia’s management of strategic risk in the new era: ‘[F]or the first time since World War II, we face an increased prospect of threat from a major power.’ We noted that the expansion of China’s military capabilities will mean that the warning time for potential contingencies will become shorter.

“China is already using coercion to challenge the presence of other countries—including Australia—in the waters of Southeast Asia. We cannot afford to have our strategic space constricted in this way. China’s military presence in the South China Sea has brought its capacity to project military power 1,200–1,400 kilometres closer to Australia’s northern approaches.

“None of this is to argue that China is necessarily going to become a direct military threat. But the simple fact is that China will increasingly have the military capability to mount high-intensity operations against us.

“We must now develop our military capabilities to deny any such threat, including access to bases and facilities in our neighbourhood.”

And in an article published the next year, Dibb added some additional insights.

“While Australia has certainly returned to embracing the geography of our immediate region as a priority determinant of force structure in the defence of Australia, the formidable strategic uncertainty we now face results in the requirement for an incomparably stronger and much more offensive ADF. It must be capable of denying any adversary from using military force—either directly or indirectly—against us.”

Professor Dibb has provided many insights with regard not only concerning Australian defence but also the broader challenges facing the liberal democracies.

If we can consider there is a return to a core focus on the direct defense of Australia and shaping an understanding of the strategic space defining Australia’s defense perimeter, how might the ADF’ current force be restructured in a template which can allow of the kind of innovation going forward that will enhance ADF direct defense capabilities?

How might new capabilities be added over the near to mid to longer term that enhance this defense restructuring to extend Australia’s direct defense capabilities?

What new innovative defense and civilian technologies can be tapped to provide for the kind of constructive disruption which Commodore Darron Kavanagh, Direct General Warfare Innovation, Royal Australian Navy, has underscored ?

This is how Kavanagh defines constructive disruption: “taking a disruptive concept from initiation through to implementation to achieve sustained warfighting effects effectively and efficiently.”

(Commodore Darron Kavanagh, Direct General Warfare Innovation, Royal Australian Navy, Keynote Address, “Autonomy in the Maritime Domain (11 May 2022).

In other words, if we focus on the priority of the direct defense to Australia, highlight what kinds of force restructuring might be necessary for the current ADF?

And then ask what new capabilities are coming into the force or could be integrated into the force in the near to midterm, what would that ADF look like as an integrated combat grid over the extended area of operations?

If one re-shifts the focus of your force, one has to ask what is most relevant and what is not in such a strategic shift; and then one needs to form the relevant concepts of operations for that force and to enhance that forces capabilities and train appropriately to shape the most lethal and survivable force possible within the various constraints facing the nation.

But that raises another key point.

If indeed the priority of the defense of Australia is from the continent to the first island chain, then the resources necessary to do so are much greater than the ADF will possess.

What kinds of infrastructure can be built in the relevant areas of sustained operations?

How to enhance force mobility throughout the region?

How to shape mobile basing options and capabilities?

In other words, Australia needs to look back and forward to achieve enhanced direct defense capabilities.

See also the following:

Prioritizing the Direct Defense of Australia: Shaping a Way Ahead for the ADF?