Shaping the Australian Defence Base for Greater Deterrent Effect

A major aspect in shaping Australia’s approach to enhanced deterrence is greater sustainability for the ADF and greater resilience for the Australian nation as a whole. Part of the equation is how to augment defence stocks and the ability to sustain the force when external supply chains are under pressure or attack.

What changes does Australia need to make to better positioned to do so?

And how does Australia work with its allies to shape a more credible allied arsenal of democracy?

Dr. Alain Dupont provided a wide-ranging overview on the challenges facing the credibility of an allied arsenal of democracy, in terms of an ability to produce weapons and other war consumables, as well as the ability to sustain equipment in higher intensity operations.

As Dupont characterized the very significant challenge facing the liberal democracies: “The country or alliance that can deliver the biggest punch and outlast adversaries will win. Right now, that is not us. The arsenal of democracy has been replaced by the arsenal of autocracy. The Ukraine conflict has exposed Australia’s and the West’s thin, under-resourced defence industrial base. If we don’t fix the problem – and quickly – we won’t prevail in a conflict with a better equipped adversary.”

Dupont illustrated his argument by focusing on the production of a key consumable in the Ukraine war, namely 155mm artillery shells.

This aspect is what the French have referred to recently as the need to have an effective “war economy” by which they are referring above all to the consumables namely, the things you need to have to fight a protracted war.

This is a key challenge as the West simply has hollowed out basic consumable production for just-in time wars supported by just-in time supply chains.

But neither the industrial base nor the supply chains are up to prolonged conflict of any sort. If Australia and the West want to deter the post-Cold war legacy approach to defense industry and supply chains will simply not be adequate. A major re-think and re-structuring is in order.

What the West can do to deal with this problem is to shape more alliance wide production and stockpiling. By realizing that the United States is no longer configured to be the arsenal of democracy, one credible way ahead is alliance-wide production, such as the recent EU decision on community wide weapons production.

But this will not happen in Australia unless the government actually funds buying the consumables necessary for prolonged operations.

Another speaker at the seminar, Kate Louis, head of Defence and Industry Policy, Australian Defence Group, underscored that although the Australian government had put in place various “push” efforts to incentivize Australian defence industry, there have not been robust, consistent and steady “pull” efforts to grow that industry. Put bluntly, if you don’t spend a steady stream of cash on munitions, as an example, industry will not build them and shape the industrial base capable of being ramped up. It is difficult to ramp up if you have hollowed out.

A second element highlighted by Dupont was more effective ways to work with the various foreign suppliers.

He noted that Australia is the fourth largest defence importer globally which means that its platforms are foreign sourced even if in some cases they are assembled in Australia.

But if the allies have tight supply chains with no real depth, how on earth can Australia expect to be at the head of the line in getting timely supplies with any tactical or strategic sustainment depth?

A major aspect of any Australian rethink must entail generating local production to support their foreign equipment, and building on a new model of an alliance arsenal of democracy, building for allied needs not just Australian needs.

This point was made by a third speaker in the defense industrial section of the seminar. Ken Kosta, Vice President, Australian Defence Strategic Capabilities Office, Missiles and Fire Control, Lockheed Martin, made this point. He commented: “Our goal is to participate in global operations which includes meeting demand in excess of Australian initiatives.

“Lockheed Martin, in partnership with the U.S. government, and the government of Australia intends to cooperatively add to near term operations, and supply chain capacity for key munitions and subsystems. In support of capability depth, Lockheed Martin plans to construct a flexible factory in Australia that can quickly adapt to meet a multitude of integration platform requirements.”

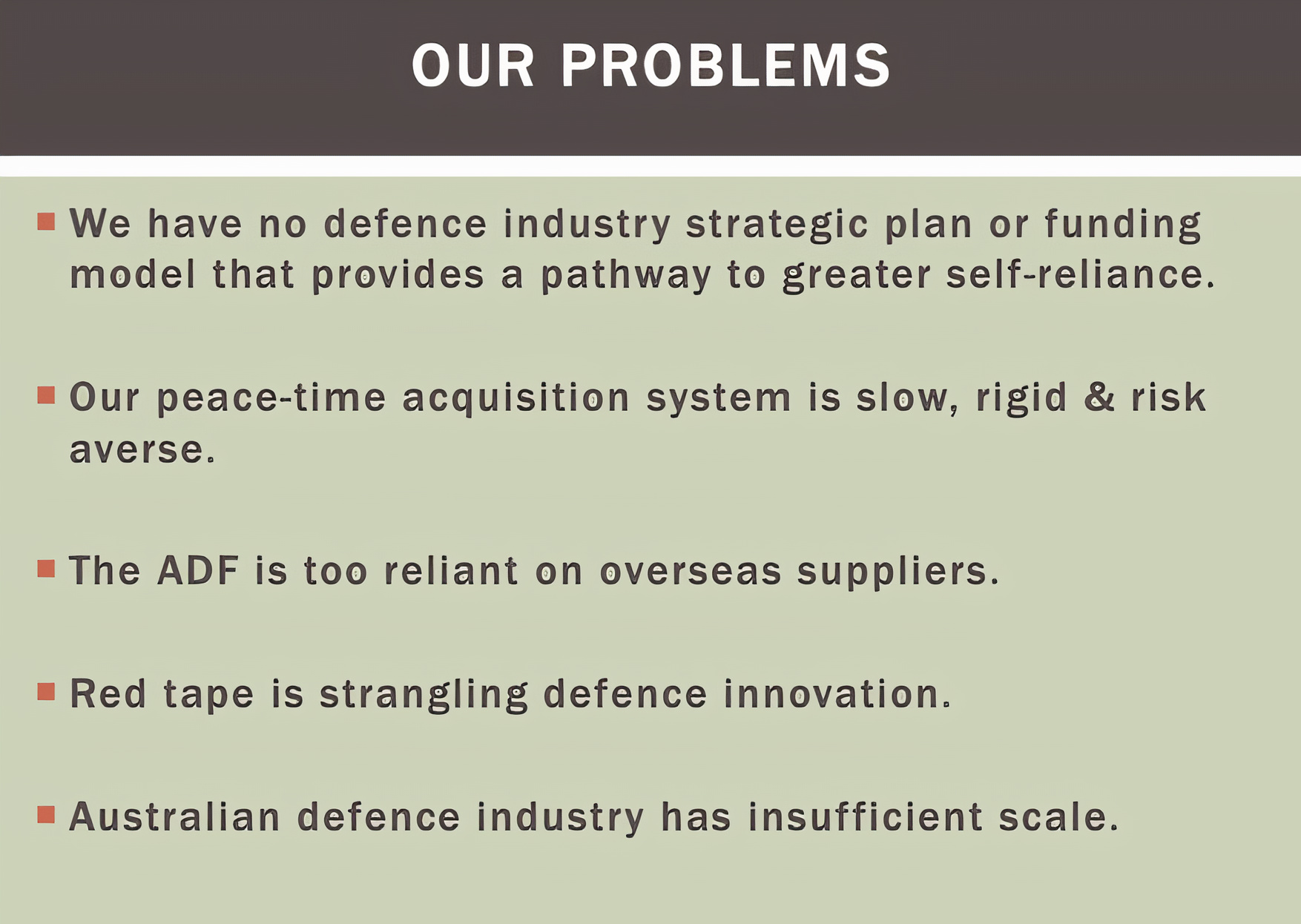

A third element discussed by Dupont are the challenges which he thinks must be met to move forward in creating a realistic and effective industry in Australia to support defense.

He summarized these challenges in a single slide in his presentation:

To shape the kind of industrial system which could support the ADF in its wider deterrence efforts, sustainability and self-reliance are critical. Deterrence is rooted in an ability to endure; not just to engage and support a 10-day military excursion.

Dupont emphasized that to be successful Australia needed to build to scale in selected sectors. He argued that in this sense, “we need to seriously invest in our own defence industry and scale-up emulating South Korea, Sweden and Israel. And that growing a competitive, export oriented defence industry must be a national priority requiring a whole of nation approach.”

But to generate the capital to build targeted industry which could become effective in export markets is a challenge to be met. In Dupont’s view: “Private capital must be incentivized to invest in defence infrastructure and national security enablers.” He argued to do so requires new approaches to partnerships between the public and private sectors.

Kate Louis also focused on the importance of government getting behind a scaling up of the defence sector, but being realistically effective in so doing. She noted: “the government has a range of levers to shape the industrial base and the industrial strategy that that wants to shape.”

But what are the objectives to be met by working in a particular defence industrial area, and will government be consistent in supporting buys from that industrial sector and support exportability of that sector?

What defense industrial infrastructure does Australia need to operate in prolonged conflict?

How can it do so?

How can it fund those capabilities?

How can government focus in a consistent way on sustaining those capabilities?

The question of industry and defence infrastructure is different in many ways from what was needed in World II. Cyber and space infrastructure are two cases in point. At the seminar, Nick Leake, head of satellite and space systems, Optus, provided a presentation which highlighted how challenging supporting and defending space infrastructure can be.

In his presentation, Leake highlighted the space network which OPTUS operates. As he put it: “the best kept secret in Australia is that we actually have a satellite business as well. We operate critical infrastructure every single day through our satellite networks. We maintain infrastructure to the highest level. And what keeps me awake at night is what could happen in space to that infrastructure.”

During the presentation, he discussed how their network serves the Australian Department of Defence as well. They operate a satellite in a particular location (as required by international regulations) to provide spectrum to support the Department.

But to operate any of their satellites within the location allowed by their international filings, they navigate the satellite within their allocated space to provide for the services provided. What Leake indicated was that they faced the significant challenge of maintaining the integrity of their satellite and its network which requires constant effort on their behalf not only for cyber security but for the physical security of the satellite itself.

What is required to ensure satellite physical security is ongoing space domain awareness (SDA). “We need SDA capability to operate our spacecraft. The SDA capabilities are extremely important for OPTUS to maintain and operate our spacecraft. This means that the SDA capability that gets built by Defence, allies and private organizations is critical to operate our space infrastructure.”

He added: “It does worry me a lot is the effect states like China which have launched more satellites than the U.S. over the past 12 months will have on our infrastructure. What are they doing with their satellites? What capabilities will they have?”

Leake indicated as well innovations which they are pursuing in the dynamic development of their space network as well. One such innovation will be seen with the launch and operation of their 11th satellite. “This will be Australia’s first fully software defined satellite. What does this mean? It allows you can alter the capacity of the satellite operating within its area of operations by altering the software to offer new services.”

Another innovation is the planned launch of a fuel pod to hook up with one of their satellites to provide more energy for the satellite to operate. The basic satellite functions well but is running low on fuel and by hooking a pod up with it, they will be able to extend the satellite’s life.

“The particular satellite in question will run out of fuel by 2026. We have decided to use what we call a mission extension pod which is fundamentally a fuel tank to extend the operational life of the satellite.”

Thus, when talking about the defense industrial base needed for Australia or its allies, one needs to widen the lens to understand what is required in terms of industrial and services infrastructure.

A final point made by Dupont was that the AUKUS agreement – which is been largely discussed in terms of nuclear submarines – could be part of reshaping how key allies can work together to shape a collaborative arsenal of democracy effort. Specifically, Dupont was referring to what has been called Pillar 2 of AUKUS.

The second pillar is focused on cooperative development between the AUKUS partners on Advanced Capabilities. The AUKUS pillar two covers an array of strategic technologies, most of which could be regarded as general technologies, or dual-use technologies. It is in this sense that Dupont argues that “AUKUS could revolutionise Australia’s defence industry if we can make both pillars work.”

Kate Louis made a similar point highlighting the need for the U.S. to deal with the way it implements its ITAR system. She noted: “AUKUS is not just a military capability, but offers a way to operatize new industrial ways of cooperation. For example, AIA (The Aerospace and Industrial Association) generated an excellent input to the Congress with regard to ITAR and Export Reform. This is really an excellent piece of work that I have not seen before in terms of driving change.”

In short, shaping an Australian enterprise to support defense in terms of the technologies most relevant to Australian deterrence is a key challenge facing Australia as well as those allies who wish to create an arsenal of democracy in common.