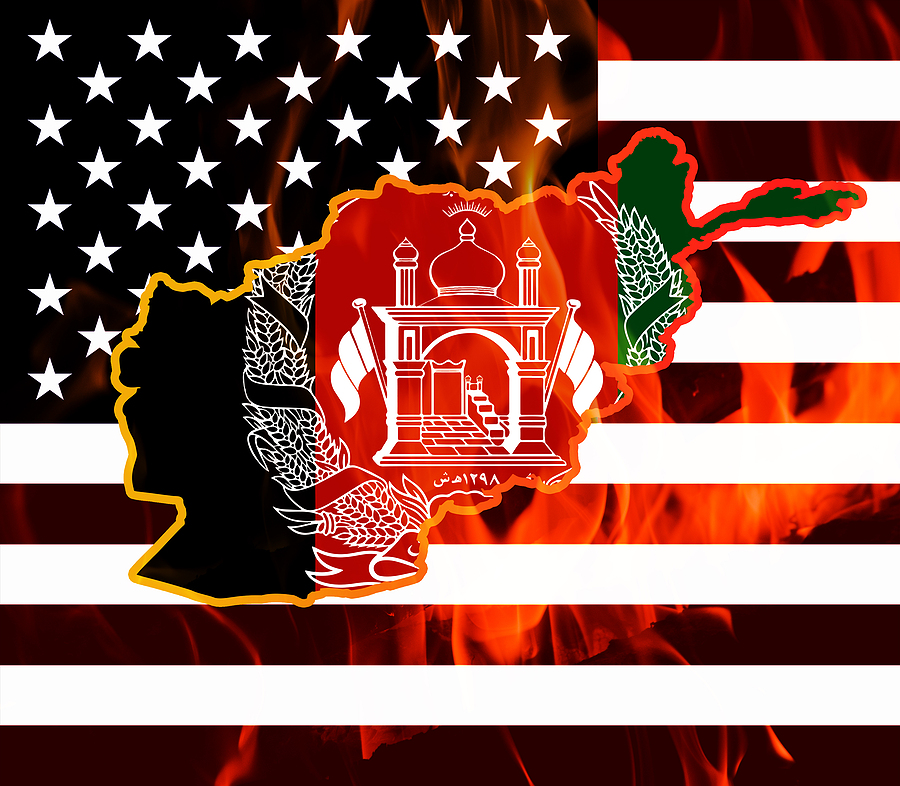

The Impact of the Biden Administration’s Afghan Blitzkrieg Withdrawal Strategy on the Way Ahead for the U.S. Military

I am currently in France, and am taking advantage of my time in Europe to discuss the impact in the near to mid-term of the Biden Administration’s Afghan Blitzkrieg Withdrawal Strategy.

In these discussions, I am focusing on assessments of how this strategy impacts allied interests and shaping a way ahead.

The claim made by Secretary Blinken is that getting out of Afghanistan rapidly will provide a key to better positioning the United States for the great power competition.

I will examine this proposition in discussions with European, Middle Eastern and Asian colleagues over the next few weeks and report back on those conversations.

But in this article, I would like to focus on the impact of the Afghan Blitzkrieg Withdrawal Strategy on the U.S. military as it engages in a strategic shift from the land wars to a focus on great power competition.

I have focused on this shift for a number of years, and have spent a great deal of time with allied and U.S. militaries on the challenge of making this transition. It is as much of a strategic shock as it is a strategic transition in that a generation of offices have really grown up in the Middle Eastern land wars, and the experiences and skill sets learned in those wars are only partially transferred to the new strategic situation.

We have highlighted a way to do this in terms of “harvest the best, and leave the rest,” a characterization proferred by Ed Timperlake.

The first key impact starts with the question of the legacy of the land wars.

Nearly a million Americans served in Afghanistan along with thousands of allied soldiers and officers.

Because this was a lengthy engagement, characterized as stability operations and nation building, those soldiers and officers trained and worked with Afghans closely to shape a way ahead, because that is the very heart of managed transition.

Then suddenly those relationships are cut by the U.S. leadership leaving those soldiers and officers in the position of having to confront the loss, death, torture, or relocation of those very persons with whom they worked for a “new” Afghanistan.

A key element of military service is honor.

This disruption and the way it is done is not in the best traditions of military honor for sure.

And a generation of officers and soldiers cannot be thrown into a political memory hole and simply asked to march forward.

The Western militaries are voluntary forces. Citizens need to want to serve, and doing so with honor to the values of their countries.

It is difficult to see how the nature of the withdrawal does not create a major set of problems for the military going forward.

The second major impact is with regard to shaping a military strategy going forward.

The Obama Administration promised a Pacific pivot which largely did not happen because of the demands from CENTCOM and the Middle East, including the rise of ISIS and the Syrian civil war.

In fact, it might be remembered that President Biden was Vice President Biden during the period of fighting the “good war” in Afghanistan.

The military focus was on counter-insurgency, nation building and that most ambiguous of terms, stability operations.

Shifting from this skill set to preparing for full spectrum crisis management and the high-end fight is significant.

Indeed, I wrote a book published this year exactly on this challenge.

How will this happen?

Will the U.S. shape a new counter-terrorism strategy in the Middle East which significantly reduces demand on U.S. forces?

If not, then frankly, the demand side is beyond what the U.S. military can provide for a strategic shift.

A third major impact flows from the second.

CENTCOM’s credibility is seriously in doubt given its performance over many years in the outcome – a failed Afghan military capability.

And with that comes the question of why the U.S. Army is in any leadership role for preparing for full spectrum crisis management and the high-end fight?

The strategic shift prioritizes air and naval forces, and those land forces which can support crisis management which is largely about the USMC and its transition to the high-end fight.

A fourth major impact is precisely the question of crisis management.

In addressing the strategic shift, my colleague Dr. Paul Bracken has focused on the central role of escalation management, inclusive of the nuclear weapons elements. I have focused on full spectrum crisis management and have underscored the importance of reshaping civilian capabilities to be able actually to use an agile military force able to respond to and provide for escalation control

The play out of the Afghan withdrawal was hardly a text book case in how to do escalation control or crisis management.

As Dr. Bracken has put it: “If our actions in Afghanistan are indicative of U.S. competence in future crises, the world is in serious trouble.”

A fifth major impact is in working with allies.

It is clear that for the U.S. military either in the Pacific or in Europe, that working closely with allies is the foundation for a credible crisis management or deterrence strategy.

And working with allies means changing how the United States military integrates with allies and partners to shape a distributed force.

Or put more bluntly, the United States is not in a position to compete with multiple authoritarian powers and to prevail without changing how the U.S. military works with allies.

This is being done on the military level, but the experience of the “runs of August” is not a reinforcing experience

If one would take just one caes: In June 2021, President Biden launches a new Atlantic Charter.

In July,2021, Sec Def Austin signs a new carrier agreement with the UK.

And in August?

In short, the U.S. military faces a number of challenges flowing from the Blitzkrieg withdrawal strategy.

How will these challenges be addressed and met?