Looking Back and Looking Forward: The Case of Ukraine

My first visit to Ukraine was shortly after it became an independent state with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The team I was working with visited Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia, with a focus on securing the nuclear weapons which the Soviet Union had controlled but abandoned inside what was now Ukrainian territory.

This was the wild west period in post-Soviet history, when in Kiev or Minsk or Moscow, the collapse of the Soviet Union left behind a society in shreds, struggling for identity.

Much of the next thirty years would see these states re-focusing on their way ahead as societies and coming to terms with the Soviet past. A major part of the Ukrainian challenge comes from the existence of divisions within Ukrainian society about how to look at their Russian neighbor compared to their European neighbors.

The focus of the United States in the early 1990s was to ensure that the former Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons came under control. The agreements reached, which saw nuclear material removed from both Ukraine and Kazakhstan, may have secured the world from a “loose nuke” concern, but in retrospect dramatically strengthened Russia’s nuclear position. Although there were no explicit security agreements to defend Ukrainian territory in case of Russian aggression, certainly giving up nuclear weapons put Ukraine in a dependent position. And from my discussions with Ukrainians, there seemed to be an assumption that becoming a non-nuclear power — the country signed the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1994 — meant the West had some sort of responsibility to work with them on their defense.

Since then, NATO and the European Union have expanded, but without both Ukraine and Belarus, the two key former Soviet republics viewed by Russian leaders to be part of the own security areas. The two have instead served as buffer states between a resurgent Russia and the new European order built since 1991. I did a study for Net Assessment in the early 1990s which focused on how challenging and dangerous this buffer zone could be to any future European order, and now here we are playing out the challenge of Ukrainian sovereignty versus the Russian view of buffer states that are part of their zone of security and influence.

During my Euro-missile work in Europe in the 1980s, a contemporary observer in terms of watching these events was Vladimir Putin. Operating in East Germany, he saw the significant struggle for European opinion, and the response of the United States and NATO to Russian military developments. He saw the divisions; he saw the conflict; and how saw how different the perspectives were among the European members of NATO.

Putin sees the fissures and dynamics of change in Europe and in NATO and has developed information war and hybrid war means to enhance his ability to shape an agenda to his liking. Putin has made it clear that the collapse of the Soviet Union in his view was a major disaster for Russia and has worked throughout his presidencies to restore a credible role for Russia in the world. At the heart of that approach is expanding the Russian influence and its defense perimeter.

But now he faces a very different challenge than did the Soviet leaders. Now he faces several European states who are keenly aware of the Russian threat. The Nordics have closely cooperated; Poland, the Baltic States and Romania, states with very clear proximate interest, have all focused on expanding their defense capabilities since the Crimean seizure in 2014. What this means is that Europeans most significantly affected by any takeover of Ukraine by Russia are prepared to respond forcefully in ways that make sense to them; Washington, in my view, is clearly challenged if it wishes to direct a whole-of-western response and shape a way ahead as the crisis is worked and resolved.

This change is really a dramatic one, and my extensive travels in Northern Europe and recent travels to Poland certainly highlight the scope and nature of the changes within the alliance since 2014. Now, key European states are often leading the deterrent effort for NATO rather than waiting for guidance from Washington.

Putin is also playing off of the U.S. relationships – economic, political and security – with Ukraine. There have been ongoing suggestions of corruption in those relationships, and whatever the truth of these charges, the Russians and Ukrainians certainly know what is either true or can be plausibly argued to be true. But simply put: in any analysis of the current U.S. position towards Ukraine and its security, it is crucial to unpack what has gone before to determine the credibility of any U.S. response.

With regard to Putin’s objectives, one can go back to look at his disputes with George W. Bush during the period of the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, to see clearly what he wants. He wants Ukraine to be like Belarus: a state dominated by leaders willing to be the loyal allies of Russia and to be part of the permanent war with the West, which was described in the July 2, 2021, Russian military doctrine statement.

While Bush simply brushed off Putin’s objections, Putin never felt persuaded to act differently; instead, he took it as a sign to wait for an appropriate time to achieve the objective of protecting the Russian security zone – Belarus and Ukraine – and rolling back Western influence. That Putin would eventually act on those desires should never have been in doubt.

As Murielle Delaporte and I put it in our book on European defense:

“The Orange Revolution in Ukraine (2004-2005) and the prospects for Ukraine to become a member of the EU and perhaps even NATO was a flash point for Putin where the new narrative of the Russian nation was to be joined by the action of seizing the Crimea and ‘returning’ it to Russia, or in this case, the new Russian republic. Put in another way, the narrative about Russia and its legitimate rights to shape its own ethnic destiny and its role as a Euro-Asian power was backed by actions. And the seizure of Crimea was very popular in Russia, to say the least. The Putin narrative underscores that revolution and state collapse is inherently bad, and the linking of the protection of Russians ‘abroad’ with the role of the manifest destiny of the Russian state is a core ideological challenge to modern Europe.”

And the current Ukrainian crisis can be seen in a wider context of European developments as well. The Russian threat to Ukrainian sovereignty is simply not about Ukraine. It is about the stability of the current European order.

The region cutting through the European continent from the Black Sea north has been an unsettled part of the post-Soviet European order. To simply take this year, the Black Sea crisis of this summer where we saw significant information war, and the “migrant” crisis generated by the Russians through Belarus against the Poles, the Balts, and the European order more generally are all part of the wider challenges which Russia is generating against the post-Soviet European order.

How Europeans and the United States shape their engagement with the Russians going forward will shape the next phase of the European order. This is not simply a Ukrainian crisis; it is much broader than that.

This is not a static thing but a moving process, whereby Brexit and the Turkish de facto exit from NATO have been key parts of reshaping the European order and the Russian pressure on their former territories is now playing a forcing function to determine who is serious about maintaining the current European order and who is not. German actions in this crisis will be critical in determining how the states who are seriously concerned about the Russian challenge and threat proceed.

After the Afghan Blitzkrieg withdrawal strategy of President Biden, how the United States shapes its response, and whether that in any coherent way represents a way ahead for the European states most affected by the Ukrainian invasion threat will be determined by actions not simply zoom meetings.

It is also the case that Russia’s challenge to the European order is part of the wider challenge of 21st century authoritarian powers to the global order as shaped by the United States, the European Union, and the democratic powers in Asia. Whatever transpires in the Ukrainian crisis is not limited to Europe.

In short, we have entered a new historical epoch which will be shaped by the concrete actions of key states and what the results of such actions will be both in fact and perceived reality.

History is on the move once again, and with it the shaping of new global anarchy or order.

An earlier version of this article was published by Breaking Defense on January 27, 2022.

Featured graphic: Photo 140260667 © Hyotographics | Dreamstime.com

Part of the study we did for DoD in the early 1990s, can be read from the DTIC archives:

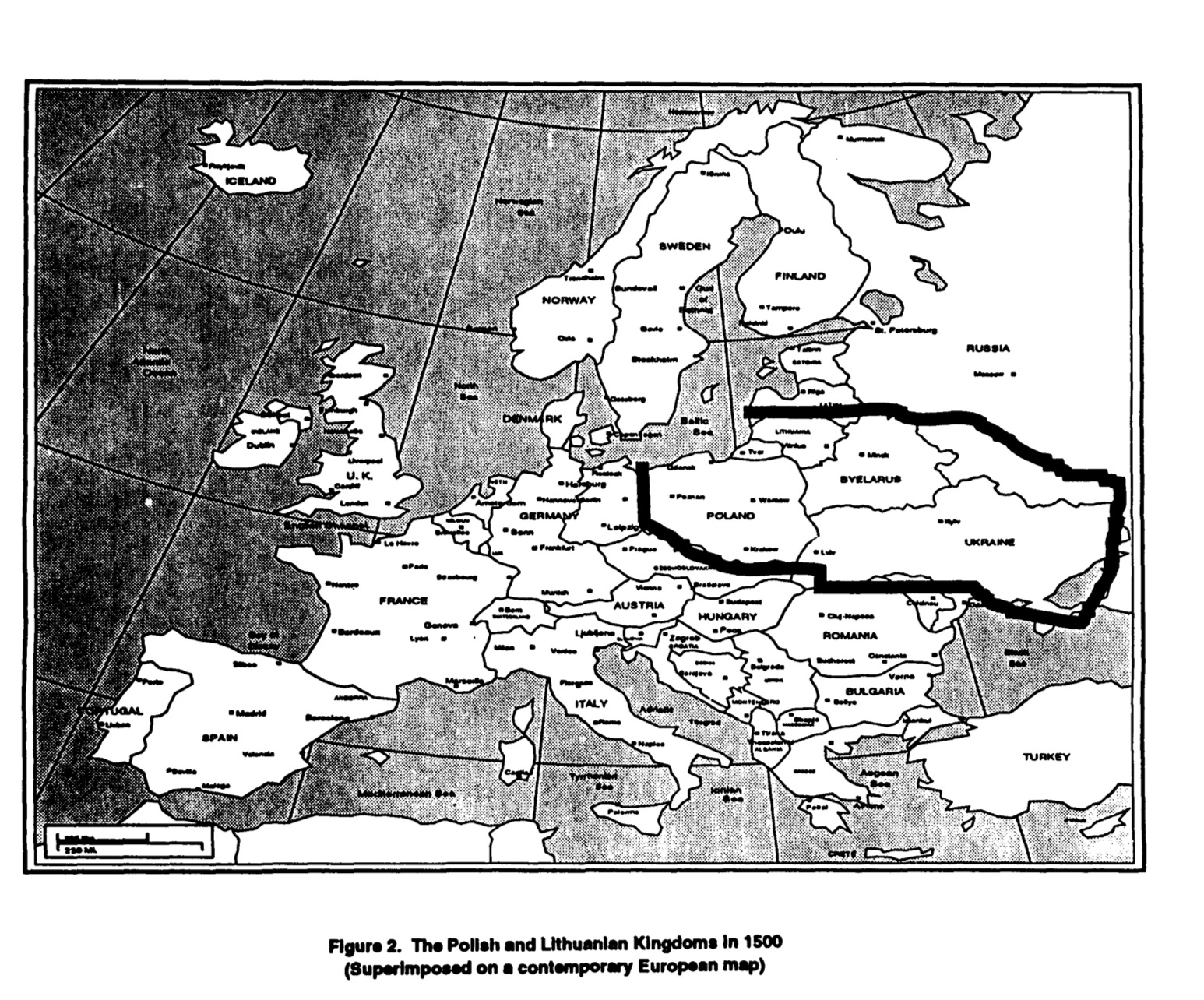

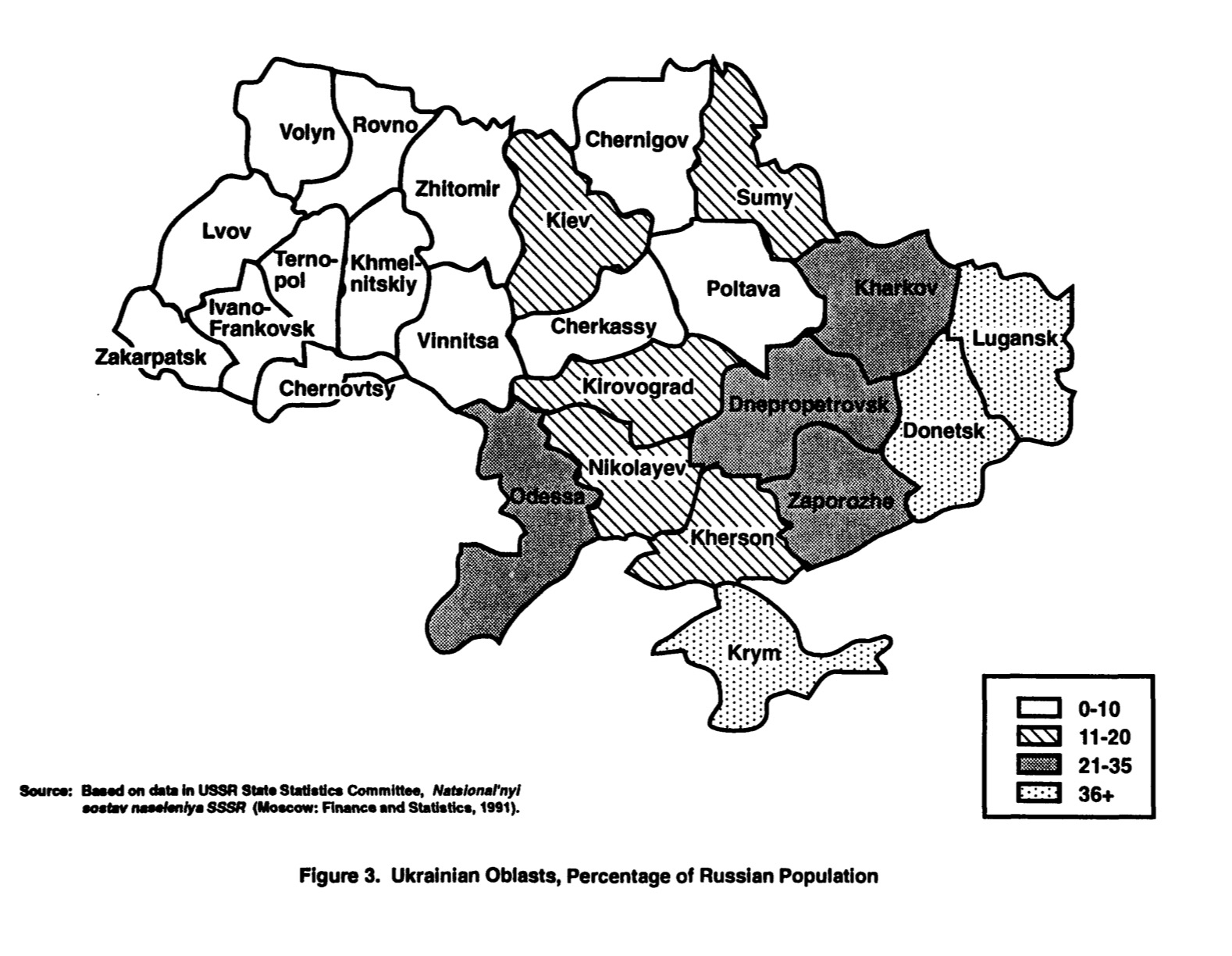

And a couple of graphics from that study highlight some interesting aspects with regard to Ukraine and its place in European history.

The first shows a view of how Ukraine was in its more European than Russian period:

The second highlights the concentration of Russians in Ukraine:

Robbin Laird and Murielle Delaporte, The Return of Direct Defense in Europe: Meeting the Challenges of XXIst Century Authoritarian Powers. (2021).