Anticipating the Chinese Challenge: The Perspective of Dr. Mark Lewis

The special report which we published in 2011 which highlighted the thinking of Dr. Mark Lewis with regard to the need to keep funding steadily the research and testing in the hypersonics field was informed by his clear understanding of the nature of the Chinese challenge.

In this 2010 interview we did with him at his office at the University of Maryland, he provided a very clear and comprehensive overview on the Chinese challenge.

The original article follows:

The Evolution of Chinese Science and Technology Capabilities

An Interview with Mark Lewis

10/29 /2010

In September 2010, Second Line of Defense sat down with Mark Lewis, President, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Willis Young Professor and Chair, Department of Aerospace Engineering.

Dr. Lewis is the former Chief Scientist of the Air Force under Secretaries James Roche and Michael Wynne.

He is a distinguished expert among other things on hypersonics.

A Chinese artist's rendering of the Chang'e-1 probe heading to a successful crash landing on the Moon (Credit: Xinhua)

SLD: As the Chinese tend to make large investments, not only internally, but also as they’re reaching out around the world in a few key areas of technology, what do you perceive to be the goals for these investments in certain areas of science and technology?

Professor Lewis: If we look at those technologies that the Chinese are investing in, not surpringly in some cases they’re the same technologies that we’re investing in.

And so, I think an obvious question is why are they doing this; what are their goals, what are their interests?

Before we address specific technical areas, I’ll tell you a very interesting story, which just happened yesterday. I got a paper to review for one of our technical journals: the author was extremely familiar with the American literature in the field – the Chinese actually read our literature very carefully – though we’re not able to read their technical literature in the way that they’re able to read our open literature.

In this particular case, it was obvious that this researcher had read our literature, because he had actually committed wholesale plagiarism out of sections of papers that were written by American researchers in his paper.

As I’m staring at this, I’m thinking that there are several aspects to this that are intriguing:

- First, the author is clearly someone who’s trying to make an entrée into the international research community and trying to do so with credentials that are being derived from another source.

- Second, it shows a familiarity with the work that we are doing in the U.S..

There are clearly several interpretations you can derive.

One is, they recognize the value of what we do, and they recognize the quality of research content.

Two, it shows a level of monitoring of the sorts of things that we’re doing.

Three, I think it shows a desire to at least match some of our activities, and to interact, maybe participate, maybe compete, maybe also collaborate in certain areas.

I’ll give you another anecdote. About 10 months ago, we had a major international conference in my own primary field, hypersonics. It was sponsored by an American organization, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

I’m actually the president of that organization this year.

The meeting was hosted by the German Aerospace Center, the DLR, in Bremen, Germany, and so it had a significant international draw.

About 30-percent of the papers submitted at that conference came from Mainland China.

Now you step back and you say what is the range of applications of hypersonics? It’s everything from reentry from space, and we know they have a robust space program, to high-speed weapons, to maybe eventually space launch vehicles. So the Chinese work could play into a full range of products, both military and civilian

But it suggests a level of investment; as one of my colleagues at the conference said, a few years ago when we would see Chinese submissions at these sort of venues, the papers were frankly less sophisticated than papers coming from Europe and the United States.

SLD: More entry level?

Professor Lewis: More entry level. Now they’re extremely sophisticated; they’re asking the right questions.

They obviously understand the work that other people are doing, which to me shows that not only are they investing the time and the effort into becoming familiar with the literature, but also they’re obviously doing their own work along the way.

They’re asking questions that show that they’re investing heavily in their own research activities.

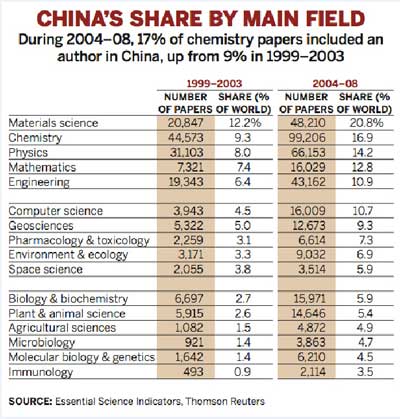

China’s share of world publications (Credit: http://www.rdmag.com)

SLD: In the 50’s, the Japanese started replicating simple technologies from Europe and the United States, then they migrated to develop some innovations of their own.

In a certain sense, part of the problem of anticipating Chinese development could well be that we’re expecting the same kind of migration, but it seems that some of the investments that you’re describing are game changing or breakthrough technologies that do not suggest simply migration.What is your sense about this?

Professor Lewis: I remember all the discussions about Japan and their increasing technological capability. Every once in a while, you’d hear the sort of sneer, a dismissive “Well, but they’re just imitative, they’re not innovative.”

Even then, I’d point out that when we train our students, we start them out in high school, and even as undergraduates, by shoveling knowledge into them.

Most of our undergraduates, learn their material by memorizing things, they learn how to do things often by rote.

They’re not creating new knowledge.

SLD: They’re iterative.

Professor Lewis: They’re iterative indeed, but when they become graduate students, the great leap to becoming a graduate student is that we expect them to be innovative.

We expect them to do research, formulate their own problems, and to develop their own approaches.

I think countries follow an analogous process.

I think that a country such as Japan or China, or frankly, any country that’s trying to build up a capability in a technology area will actually start out by first learning what others have done.

When I start a graduate student on a research problem, I say go to the library, read the papers, and see what other people have done. And then they start formulating their ideas, they understand the advances, they understand the shortcomings, and then they begin to build on that to do their own innovation.

I think that’s what we’re seeing across the board with the Chinese. Hypersonics is one of those areas where a few years ago we saw that they were just getting up to speed in the area. They were just, obviously, reading the papers in the open literature. And now we’re seeing them presenting and developing new ideas. Exploring the field, presenting papers on basic research, building facilities. So that’s one aspect.

There’s another element that I think we have to remember, and that is that quantity has a quality in and of itself. Again, I’ll often hear people say dismissively, “well yes, the Chinese are producing many more engineers, but they are not up to the standards that we have,” (although in many cases, they are). And to that I’ll answer “well, if we’re producing a thousand experts in our field, and they’re producing 10,000 experts in the field, and if 10-percent of their people are as good as the people we’re producing, they’re still doing pretty well.

If you generate a certain volume of expertise in a field; if you invest a certain amount in the field, not only in dollars, but also across the board in the workforce, you’re bound to see benefits.

We’ve seen the ability to leapfrog in technology. My friends in directed energy tell me that they have seen advances in the open literature in what the Chinese are doing that really surprised them, that they were moving at a pace that was much faster than anyone had previously expected.

I think a lot of that is just putting in a lot of resources.

We’ve done that in the past in our country, in the Manhattan project: when you think about the investment in the Manhattan project, we were able to realize incredible technological accomplishments with massive investments.

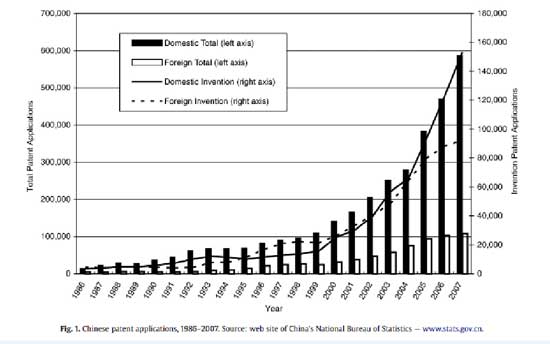

Chinese patent applications (Credit: http://faculty.smu.edu)

Chinese patent applications (Credit: http://faculty.smu.edu)

Other example: the B-29 Bomber. It’s one of my favorites from aeronautics. We basically sunk a lot of money and a lot of resources and a lot of manpower and produced an aircraft that, at the end of World War II, was literally a generation beyond the aircraft that have preceded it.

So when you make those sorts of investments, and especially when you’re in a country where labor isn’t that expensive, you can have these incredible accomplishments.

And I think it behooves us to step back and say well, why are they making these investments?

What are their goals, what are they after?

I think that’s a question all of us with an interest in this subject should ponder.

SLD: It’s pretty clear that aerospace, generally, has been identified as an important growth area for them, commercially and militarily, but we should remain a bit humble in assuming we understand what the Chinese science and technology growth model might be, don’t you think?

Professor Lewis: Correct. For quite some time, we’ve had a very high number of Chinese students in the United States educational system.

The joke is that there are some science and engineering departments in the United States where the dominant language is Mandarin Chinese.

And that’s been the case for many years.

What we’re seeing in recent years, including on a campus such as ours, is a rather profound change. Whereas 10 years ago, when we had Chinese students arrive, their goal was generally to stay in the United States.

They wanted to get an education here and they wanted to become Americans, and they wanted to work in American technology.

And so the question they’d ask is how do they become citizens?

How do they become part of the American experience?

Now more and more, we are seeing students whose goal is to learn, and then go back to their homeland and bring the lessons that they’ve learned here back to their home country. In many cases, they see more opportunities; they see tremendous economic opportunities there.

They also see, I think, social opportunities to advance faster in their home country than they see here.

To a certain extent, I think we’ve hurt ourselves when we have created barriers for some of these folks to remain here, though in some cases we have done so for very good reasons.

But as a byproduct, we are essentially helping to create our own competition.

Clearly there are crosscutting choices or trends.

On the one hand, you don’t want to close your doors entirely; the free flow of information, the exchange of ideas is one of the things that drives the scientific community.

When you clamp down strongly, then you hurt yourself; you limit your own ideas, you wind up getting stuck in your own sandbox.

So bringing in fresh ideas, having an international exchange is a normal part of academic life.

There are really smart people all over the world. And so you don’t want to stop that sort of free flow of information when it’s appropriate.

When I was on the Air Staff I’d always point to the example of the United States Air Force having very robust international research programs. The Air Force has a research office in Tokyo, a research office in London, and just opened up a research office in Santiago, Chile.

They fund researchers around the world, and there are many good reasons for doing so.

There are smart people all over the globe that you want to tap into them. There’s also the argument that when we bring people in from overseas that they learn about us; they learn about our systems, they absorb our values, they learn why this is such a great country. And I think they carry that message back.

But of course, there’s also the flipside, which is that we wind up in some cases, selling the farm. We wind up giving away technologies, giving away knowledge. It’s that fine line that I think we’re frankly very challenged by, and that in some cases we’ve seen other potential adversaries, potential competitors exploit and use against us.

SLD: It seems that we’re really at a crucial crossroads or threshold: on the Chinese side, if they don’t commit to serious protection of intellectual property, it raises fundamental questions about what the strategic purpose of their goal is.

On the other side, if the United States, as well as Europe, do not get more serious about competitive manufacturing capability; about their own projects in aerospace and defense, then we will only have ourselves to blame for losing the competitive race.

Professor Lewis: Right. I would agree.

One of the policy issues I was most concerned about on the in aerospace occurred a few years ago, when the Chinese launched their first astronauts. I was actually expecting kind of a hue and cry from Americans saying wow, look at that.

We’ve got to get back into a little bit of competition. It’s not bad competition, but let’s robust our space program. We saw that in Sputnik, right? The Russians launched Sputnik and there was a national panic that we were allowing our science/technology to whither.

But when the Chinese launched their astronauts, it was buried in the back of page 3 or 4 in the Washington Post, and you heard very few comments. I’ve heard people prognosticate that the Chinese will probably be back to the moon before we get back to the moon. And at the rate we’re going, that’s almost certainly true.

Where’s the popular concern?

SLD:One thing about the Chinese space program is that there is an assumption that we’ve already done it, and therefore we don’t have to do it. And it goes back to your proposition of quantity is a quality all of its own.

They’re investing; they’ve got thousands of engineers in the space program. We may make the judgment that well, it’s repetitive, and so what do you get out of it?

The problem is that we’ve gone through a period of global dominance and there are assumptions that we can drift along and still be dominant.

People tend to be confusing an event or a program such as returning to the Moon with a particular historic moment.

And not understanding the question is an investment in an overall capability at a different moment in history.

Does that make sense?

Professor Lewis: I would agree with you completely.

We know that they’re investing in space, and openly talking about their aspirations in both civil and military space.

Take one example: materials development is a tremendous driver for aerospace. The Boeing 787 is an example: its great advance is the use of composites instead of metal. Mike Wynne, when he was secretary, understood this very well, and he placed a very strong emphasis on composite materials coming into the air fleet.

We know that the Chinese are investing very heavily in that area as well.

Materials technology development has military applications; it has civilian applications as well. Directed energy is another bellwether field.

We know from their publications in the area, that they’re very interested in lasers. Laser technology has applications across the board, everything from telecommunications to defense applications.

I think it’s pretty clear that they’re investing heavily in cyber, and we know that they’re making significant inroads in cyber technology; I think the military applications there are obvious.

In many cases, I’m intrigued because it looks like the Chinese have gone back and looked at where we were talking about making investments in the past, and maybe sometimes we didn’t make the investments, but they are.

The other point I’d make is that they’re making an investment in long-term education. I’ll tell you another interesting story; shortly after I came back to campus full-time from the Pentagon, I found out that we have an exchange office on campus that was actually bringing in a group of Chinese faculty members who are coming to our university.

Their goal was to sit in our classes and learn how we teach, and what material we teach, and then go back to their home institution and teach those same sorts of classes.

The intriguing thing was, they weren’t necessarily interested so much in the specifics of our course material, they weren’t interested in that. Instead, they were interested in our delivery methods.

How do we actually instruct our students?

What processes do we put our students through?

That bespeaks a long-term investment in education, which cuts across disciplines.

And of course, they’ve got a very close relationship between their universities and their military infrastructure. And in many cases, their universities serve as designed bureaus for their military, so there’s a very close coupling.

SLD: One way to look at this is that there’s a strategic vacuum in the West. You have this kind of strategic vacuum or pause or however you want to characterize the situation; it’s not moving forward.On the other hand, China is becoming a strategic juggernaut.

So you put this strategic Chinese dynamic with a Western strategic pause, you create a different phase in the global competition. Strategic vacuums interacting with strategic juggernauts have a strategic consequence.

And that’s really the point.

Professor Lewis: I would agree with you completely. If I look across the board at aerospace technologies, we have essentially produced only two new rocket engines in the last 30 years. In many cases, we’re coasting in technology.

In the aircraft area, how do we build on design experience?

What comes after the F-35?

We’re not even really having those conversations yet to think about how we’re going to be developing our future systems.

With regard to airliners, we have a lot of advanced ideas on the drawing board, but not a lot of real programs. NASA’s got concepts for future air and space systems; the Air Force has a lot of concepts as well.

But even when you look at something as modern as a 787, as you correctly point out, it’s building on older technology and our hard-earned knowledge base.

So, I’d almost invoke the classic rabbit and tortoise analogy; if the rabbit makes great leaps, but then stops and rests on its laurels, it’s relatively easy for the tortoise to catch up. That’s especially true if the tortoise gets himself supercharged, and if after he’s caught up, he takes off at rapid speed.

I think that in general we tend to see examples where there’s a tendency to invest in a certain level of technology, and then coast.

Railroads are a perfect example.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the United States had a phenomenal railroad system.

Our railroad system was the envy of the world.

But once built, we didn’t invest very much in it.

Now you look at Europe, Asia, their rail systems are far superior to ours because they invested later on and they got newer technology.

We stopped making those major investments.

SLD: And a key development is the intersection between the new manufacturing base in China, the Manhattan style investments, and the growth in S and T capabilities. It has a magnet effect on the rest of the world as well. Let me give you a story, which reflects on that intersection. I listened to a presentation from Michelin about how they were inverting their supply chain role to becoming a prime manufacturer of automobiles.

And the strategic partner is China. And the entire concept from the Michelin side is a tire is something that you put on, the car generates everything else. But in fact, if you start thinking about electric propulsion or internal propulsion systems, you can put much of what’s in the rest of the car on the tire.

And they’ve actually got designs for this.

Who’s their strategic partner? China. Chinese are investing heavily in this technology area. It’s just a natural thing attracted by the marketplace, the investments, and the manufacturing base.

So I think we’ve also deluded ourselves that in establishing a very significant manufacturing base in China, there are no strategic consequences, because they’re kind of like Japan.

They’re not Japan.

Professor Lewis: Right, exactly. I remember General Moseley was asked if he really thought the United States Air Force would be facing a Chinese military threat at some point in the future?

And I think he made the very profound observation that the chances that we’ll be facing off directly against China are extremely small, but the chance that we’d be facing off against their equipment in the future is actually quite high.

Unfortunately, a lot of the reporters picked up the first part of the quote, and they didn’t pick up the second part of the quote.

I had an experience when I was the Chief Scientist of the USAF on a trip to Brazil, which highlights this point. During my visit, the Brazilians took me to their space agency and they walk me into a facility where they’re assembling satellites.

They have very ambitious plans for space; they had been trying to build their own launch system, they were looking at microsatellites.

And I always remember that visit, because they walked me into big high bay area, their assembly area for satellites.

They took me up to the fourth floor, I went out onto this sort of balcony area, I’m looking down, standing behind a pane of glass.

And on the floor of the facility are about 30 or 40 Chinese engineers working hand-in-hand with the Brazilians. I asked what’s going on here?

The answer was the Brazilians had a wonderful working relationship with the Chinese.

The irony was that all their equipment was American-made; they had American shaker tables, they had American environmental chambers to test their satellites.

But the guys on the floor who were working with them were Chinese.

And oh by the way, I asked what’s the language for communication? Oh, English.

The Chinese spoke English, the Brazilians spoke English, so they’re all speaking to each other in English.

And I asked the Brazilians, “Well, why aren’t you working with us?”

And the answer I got was, “It’s too difficult.”

That was interesting.

———-

Additional reference:

The below quote from a paper looking at Chinese development underscores forcefully the key point Professor Lewis is making about leap ahead capabilities.