The Return of Direct Defense for Northern Europe: Not Your Daddy’s Cold War

With the Russian takeover of Crimea, the end of the post-Cold War era came with it.

And as Putin continued to ramp up the challenges to the West, gradually political processes in the West began to focus on the return of direct defense.

Although counter-insurgency remained a key skill set, now Western militaries had to face once again the threat of force-on-force confrontations, and the challenge of returning to core tasks, which had atrophied, such as anti-submarine warfare and air superiority.

Not long ago, President Obama and Secretary Gates heralded the cancellation of the F-22 as a good idea because it was a “Cold War” combat asset. Then the Cold War returned, some one would argue not an unpredictable development.

But it is not a return to the Cold War, but something different, one with Cold War elements, but in a very changed strategic situation.

This is becoming increasingly clear in Northern Europe where I have conducted several visits over the past few years interviewing political, strategic and military leaders about how to shape a way ahead to deal with the new Russia and the evolving Western policies, leaders and threats.

It is clearly not your Daddy’s Cold War for the younger generation, but having not lived through it, it can be a bit of a shock facing a nuclear power, which has several times threatened Northern Europe with destruction if they don’t comply with how the Russians want to see security and defense develop in Europe.

But there is no Warsaw Pact.

The Russians can not lead an envelopment campaign in the event of war against Northern Europe.

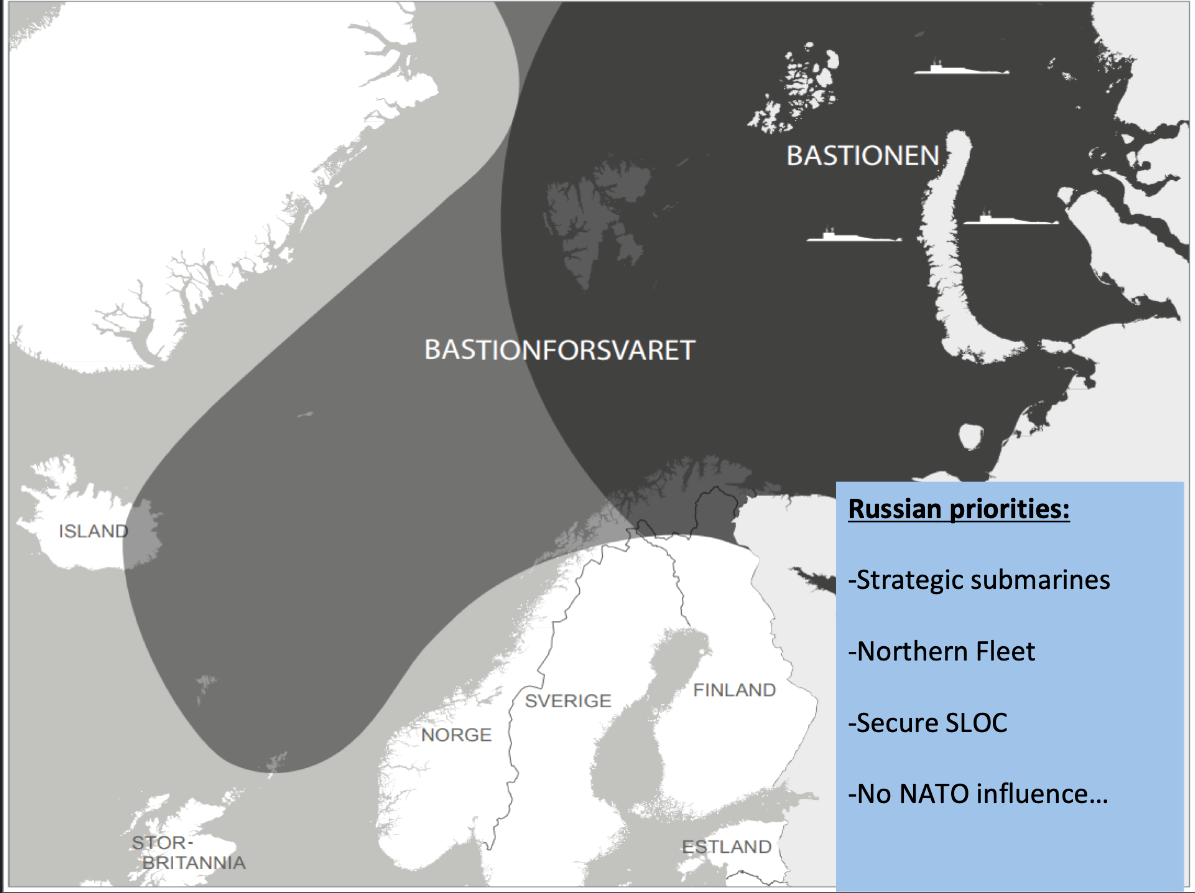

The Russians maintain the greatest concentration of military power on earth in the Kola Peninsula, which makes Northern Europe a key flashpoint for the Russians as they push out usable military power to areas of interest, including in the Middle East.

The opening of the Arctic is changing the strategic geography as the Russians stand up new military bases, including air bases to provide greater reach and range affecting their ability to move force out into the North Atlantic.

And for the Nordics, it is the extended reach of Russian strike capability, notably longer-range missiles, which also change the threat calculus.

A very clear statement of the strategic shift was provided during a visit last year to Denmark by Admiral Nils Wang former head of the Danish Navy and then head of the Danish Royal Military Academy who clearly differentiated the Soviet Union and its Cold War threat calculus from the Russian threat the Nordics now face.

Wang clearly argued that the Russian challenge has little to do with the Cold War Soviet-Warsaw Pact threat to the Nordics. The Soviet-Warsaw threat was one of invasion and occupation, and then using Nordic territory to fight U.S. and allied forces in the North Atlantic. In many ways, this would have been a repeat of how the Nazis seized Norway during a combined arms amphibious operation combined with a land force walk into Denmark.

In that scenario, the Danes and their allies were focused on sea denial through use of mines, with fast patrol boats providing protection for the minelayers.

Aircraft and submarines were part of a defense in depth strategy to deny the ability of the Soviets to occupy the region in time of a general war.

He contrasted this with the current situation in which the Russians are less focused on a general war, and more on building capabilities for a more limited objective, controlling the Baltic States. He highlighted the arms modernization of the Russian military focused on ground-based missile defense and land- and sea-based attack missiles, along with airpower, as the main means to shape a denial-in-depth strategy which would allow the Russians significant freedom of maneuver to achieve their objectives within their zone of strategic maneuver.

A core Russian asset is the Kalibr cruise missile, which can operate off of a variety of platforms. With a dense missile wolf pack, so to speak, the Russians provide a cover for their maneuver forces. They are focused on using land-based mobile missiles in the region as their key strike and defense asset. “The Russian defense plan in the Baltic is all about telling NATO, we can go into the Baltic countries if we decided to do so. And you will not be able to get in and get us out. That is basically the whole idea,” the admiral said.

Wang argued for a reverse engineering approach to the Russian threat. He saw this as combining several key elements: a combined anti-submarine (ASW), F-35 fleet, frigate- and land-based strike capabilities, including from Poland.

The admiral’s position is based in part on the arrival of the F-35 and notably the F-35 as a core coalition aircraft designed to work closely with either land-based or sea-based strike capabilities. “One needs to create air superiority, or air dominance as a prerequisite for any operation at all, and to do that NATO would need to assemble all the air power they can actually collect together, inclusive carrier-based aircraft in the Norwegian Sea,” he told me.

“This is where the ice free part of the Arctic and the Baltic gets connected. We will have missions as well in the Arctic at the northern part of Norway because the Norwegians would be in a similar situation if there is a Baltic invasion.”

The rear admiral argued as well for a renewal or augmentation of ASW capabilities by its allies to deal with Russian submarines in the Baltic there to support operations, notably any missile-carrying submarines. He saw a focused Danish approach to frigate/helo-based ASW in the region as more important than buying submarines to do the ASW mission.

The importance of using the F-35 as a trigger force for a sea-based missile strike force suggests that one option for the Danes will be to put new missiles into their MK-41 tubes which they have on their frigates. They could put SM-2s or SM-3s or even Tomahawks onto their frigates dependent on how they wanted to define and deal with the Russian threat.

And during my visit to Denmark in April 2018, the Danish Defence Minister provided an overview on how the government views Danish and Nordic defense and security during a conference hosted by the Danish Atlantic Treaty Organization. The Minister provided a broad overview of what he saw as the challenges involved in the direct defense of Denmark and Europe.

In his presentation and in his response to questions, he focused on a number of key challenges, such as cyberwar posed by the Russians, which are really part of a broader threat calculus, which focused on the need to enhance infrastructure defense for Denmark and its allies. Put in other terms, the notion of domestic security and national defense was clearly blurred in an era where the Russians had expanded their tools sets in going after Western infrastructure, and by blurring the lines between peace and war.

In effect, the Danes like the other Nordics, are having to focus on direct defense as their core national mission, within an alliance context. This will mean as well a shift common to other alliance members from a focus on out of area operations, such as in Afghanistan, back to the core challenge, namely, the defense of the homeland.

Russian actions starting in Georgia in 2008 and then in the Crimea in 2014 have created a significant environment of uncertainty for European nations, one in which the refocus on direct defense is required.

Denmark is not only earmarking new funds for defense, but buying new capabilities as well, such as the F-35. And they are reworking their national command systems as well as working with Nordic allies and other NATO partners on more effective ways to operate to augment defensive force capabilities in a crisis.

It was very clear from discussions during my visits to Finland, Norway and Denmark this year that the return of direct defense is not really about a return to the Cold War and the Soviet-Western conflict. Direct defense has changed as the tools available to the Russians have changed, notably with an ability to leverage cyber tools to leverage Western digital society to be able to achieve military and political objectives with means other than direct use of lethal force.

This is why the West needs to shape new approaches and evolve thinking about crisis management in the digital age. It means that NATO countries need to work as hard at infrastructure defense in the digital age as they have been working on terrorism since September 11th.

New paradigms, new tools, new training and new thinking is required to shape various ways ahead to shape a more robust infrastructure notably in a digital age.

Article III within the NATO treaty underscores the importance of each state focusing resources on the defense of its nation. In the world we are facing now, this may well mean much more attention to security of supply chains, robust infrastructure defense and taking a hard look at the vulnerabilities which globalization has introduced within NATO nations.

Put in other terms, robustness in infrastructure can provide a key element of defense in dealing with 21stcentury adversaries, as important as the build up of classic lethal capabilities.

The return of direct defense but with the challenge of shaping more robust national and coalition infrastructure also means that the classic distinction between counter-value and counter-force targeting is changing. Eroding infrastructure with non-lethal means is as much counter-force as it is counter-value. We need to find new vocabulary as well to describe the various routes to enhanced direct defense for core NATO nations.

It is also clear that a new strategic geography is emerging in which North America, the Arctic and Northern Europe are contiguous operational territory targeted by the Russians and the NATO states need to focus on ways to enhance their capabilities to operate seamlessly in a timely manner across this entire chessboard.

The Nordics have clearly enhanced their cooperation and with Poland and the Baltic states as well in an effort to shape more interactive capability across a common but changing strategic geography.

It is changing as the Russians evolve the reach and lethality of their air and maritime strike capabilities.

An example of a very different dynamic associated with direct defense this time around is how to shape a flexible basing structure.

What does basing in this environment mean?

How can allies leverage national basing with the very flexible force packages which will be needed at the point of defense or attack to resolve a crisis?

In short, this is not a new Cold War. There is a return to direct defense as the primary task for the Northern European nations, rather than out of area activities.

But now the very tasks, which direct defense need to deal with, have changed, expanded and mutated.

The sponsor for the conference hosted by the Danish Atlantic Treaty Organization was Risk Management, a firm created by and run by Hans Tino Hansen, a well known Danish security and defense analyst. He put it this way about the new context and challenges facing Denmark and the Nordics:

“We need to look at the Arctic Northern European area, Baltic area, as one. We need to connect the dots from Greenland to Poland or Lithuania and everything in between. We need to look at the area as an integrated geography, which we didn’t do during the Cold War.

“In the Cold War, we were also used to the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact being able to actually attack on all fronts at the same time, which the Russians wouldn’t today because they are not the power that they used to be. And clearly we need to look beyond the defense of the Baltic region to get the bigger connectivity picture.”

“NATO is also not what it used to be as well.”

“We clearly need to rethink and rebuild infrastructure and forces to deal with the strategic geography which now defines the Russian challenge and the capabilities they have within that geography to threaten our interests and our forces.”

“We need to evaluate the threats across a spectrum of conflict, that is also what is so different today compared to the Cold War. We clearly need to enhance our force structure to be able to do classic direct defense as this is key to credible deterrence.

“But now we face a range of threats in the so-called gray area which define key aspects of the spectrum of conflict which need to be dealt with or deterred.”

We then discussed the key challenge of reshaping civil structures that actually can address crisis management of the sort necessary to deal with the wider spectrum of Russian tools as well. For this we need a system of crisis identification and to establish robust procedures for crisis management.

“A crisis can be different levels. It can be local, it can be regional, it can be global and it might even be in the cyber domain and independent of geography.”

“And, we need to make sure that the politicians are not only able to deal with the global ones but can actually also react to something lesser.

“Who knows when a crisis is a crisis? Is it when X amount of infrastructure has been attacked by cyber-attacks? Is it when X amount of public utilities have been disrupted and for how long that defines the nature of a crisis?

“This certainly calls for systems and sensors/analysis to identify when an incident, or a series of incidents, amount to a crisis”.

“Ultimately, that means that the politicians need to be also trained in the procedures necessary in a crisis similar to what we did in the WINTEX exercises during the old days during the Cold War where they learned to operate and identify and make decisions in such a challenging environment”.

In short, the Russian challenge has returned but not understood in an historic Cold War context, but a 21st century one.

And it is one in which direct defense has changed in terms of incorporating new infrastructure threats and challenges as part of any comprehensive defense concept which Europe and North America needs to shape and build.

Featured Photo:Russian President Vladimir Putin giving his annual state of the nation address earlier this year. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko)