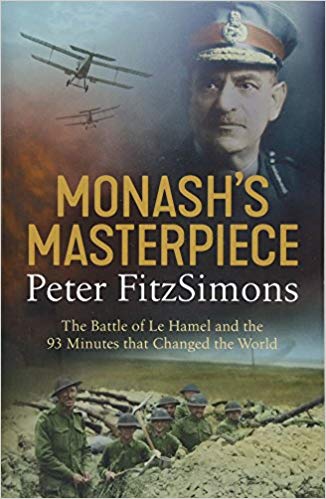

Monash’s Masterpiece: The Battle of Le Hamel and the 93 Minutes that Changed the World

Peter FitzSimmons has written a trilogy of books focused on Australia and the First World War.

This book focuses specifically on an aspect of the First World War that is little known outside of experts or World War I buffs.

But it is a story which deserves to be widely told and FitzSimmons book provides an outstanding opportunity for our readers to become either familiar with or gain more detailed knowledge of the role of the Australian general who pioneered a combined arms approach to offensive operations and broke the mold on how World War I operations were conducted up to that time.

The book is written in the present tense and draws heavily on diaries and histories of the period and allows the reader to go back in time to gain an understanding of the context and in the preparation for what would turn out to be a breakthrough battle, the battle of Le Hamel.

The battle was fought and won in less time than it takes to read the book.

It was fought on July 4 1918 and was the first engagement which involved Americans who fought under Australian command and also was a founding moment for what would become the very solid American-Aussie relationship.

The Americans were involved in the battle against the wishes of General Pershing who had insisted that Americans be held out of the war until 1919 when he felt they would be ready.

Nonetheless, the Americans were integrated into the Aussie forces and were key participants in the battle despite General Pershing.

And it was clear from the conduct of the Americans that the troops were more than eager to go into battle and in fact attacked the Germans with the cry: “Remember the Lusitania!”

In a classic moment after the victory, the French Prime Minister hosted Generals Haig and Pershing to thank them for the victory. Pershing did not say anything during the ceremony but afterwards was keen for this to not happen again and he made it clear that the Americans participated against his direct orders.

But the Aussies and Americans simply had too much in common for even Pershing to block the way.

“For their part, most of the American soldiers are impressed (with the Aussies), with private Charles D. Ebersole, of Chicago, recording his impression that the Australians are ‘very good,’ and ‘very democratic,’ although ‘somewhat undisciplined.”

“In short, exactly their kind of blokes.” 1

Monash was an engineer rather than a professional soldier; and he was resented by some fellow officers because of this fact.

But as an engineer, he focused on ways to leverage the engines of war to reshape how an offense could be conducted, rather than simply using human combat mass to win the day.

His original plan was to take the German positions at the village of Le Hamel by a combined air, tank and infantry operation. But his style was to plan an offensively carefully, brief the plan and get the key experts involved in the plan.

As a result, he changed the plan to make key use of various artillery capabilities integrated with a phased air and tank-infantry operation.

He insisted on getting high grade intelligence with regard to the disposition of the German forces and to work carefully on crafting an offensive in which each element of the combined force would then be used with particular effect in a coordinated offensive assault.

The Aussies had been used first in World War I in the disaster of Gallipoli; but they would end the war becoming the tip of the spear of the allied forces in shaping offensive operations.

Following, Le Hamel, similar tactics would be used at Amiens with similar results.

“In no small part due to the exertions of Sir John Monash and his men, and the example they set at Hamel – which was then replicated many times over – the war was won within weeks.” 2

“In short, courtesy of Monash (Allied) GHQ made it official: the days of just sending waves of men at enemy trenches and hoping to overwhelm them by sheer force of numbers are mercifully gone. From now on, the key is to is to use ‘fighting machinery,’ the tanks, the planes and guns to do much of the heavy lifting as, through rapid, coordinated attack against a surprised enemy, you overwhelm their resistance and use your soldiers to mop up and consolidate the ground won.” 3

The ability to leverage technology and to combine technology with well-planned combat operations for an integrated force was important then; it is even more important now.

And the example of Monash as engineer rather than a traditional General might also be important was we work the skill levels for a 21stcentury combat force to succeed.

The Monash story also reminds us that to invent an innovative approach is important; but when your enemy learns how to do it better than you and you tend to forget what you did, it may not turn out so well.

As we would learn when the Germans migrated this approach into the Blitzkrieg of 1939. It is not enough to innovate and forget; it is important to build from your innovations and keep on innovating.