Australian Defense Strategy in Transition: The Perspective of Paul Dibb

During my past three years, I have seen significant change within the Australian strategic community in their discussions about the way ahead for Australia in the new strategic situation.

At the heart of those discussions is the understanding that an enhanced regional focus is becoming more important with regard to Australian defense and strategy and with that focus, reshaping how the Australian Defence Force operates within the region and how it’s evolving fifth generation capabilities need to be shaped and transformed in dealing with the regional challenges.

There is a growing recognition that as an island nation, Australia faces the potential disruptions or tactical or strategic denial which our partners in globalization, the 21st century authoritarian states could exercise in a crisis.

At the most recent Williams Foundation Conference, Brendan Sargeant, the well-regarded Australian strategist with a very significant track record working on such issues for many years within the Australian government, provided an overview on how he saw the challenges of transition.

We are at one of those points in world history when the strategic order is changing. This has been the central topic of discussion in policy and academic circles for the last decade. It was foreshadowed in the 2009 Defence White Paper and elaborated in different ways in the 2013 and 2016 Defence White Papers. It haunts the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper.

This sense of change has become more acute over the past two or three years to the point where it seems to be generally agreed in commentary circles that the 2016 Defence White Paper is no longer adequate as a frame for understanding our strategic environment, or as a vehicle to guide future policy development. So, the question is: what now?

I have often commented that in our strategic assessments and policy development, we have consistently underestimated the rate of change in our strategic environment. Perhaps this is the equivalent in policy circles of the often discussed ‘Conspiracy of Optimism’ in project management.

However, that said, I personally have been astonished at how quickly the consensus has emerged across policy and academic communities that the world has changed irrevocably and that we are not certain about what sort of future we are going into.

He kindly acknowledged the conversations we have had over the years as well as the interactions with have had together with Paul Dibb.

I would also like to put on record my appreciation for the help that Robbin Laird and Paul Dibb, in our many conversations, have given me in thinking about some of these issues.

The readers of Second Line of Defense and Defense.info have had the chance to share my views with regard to the evolving strategic situation, and what I have learned over the years with regard to the evolution of Australian policies and thinking about competing in the new strategic situation.

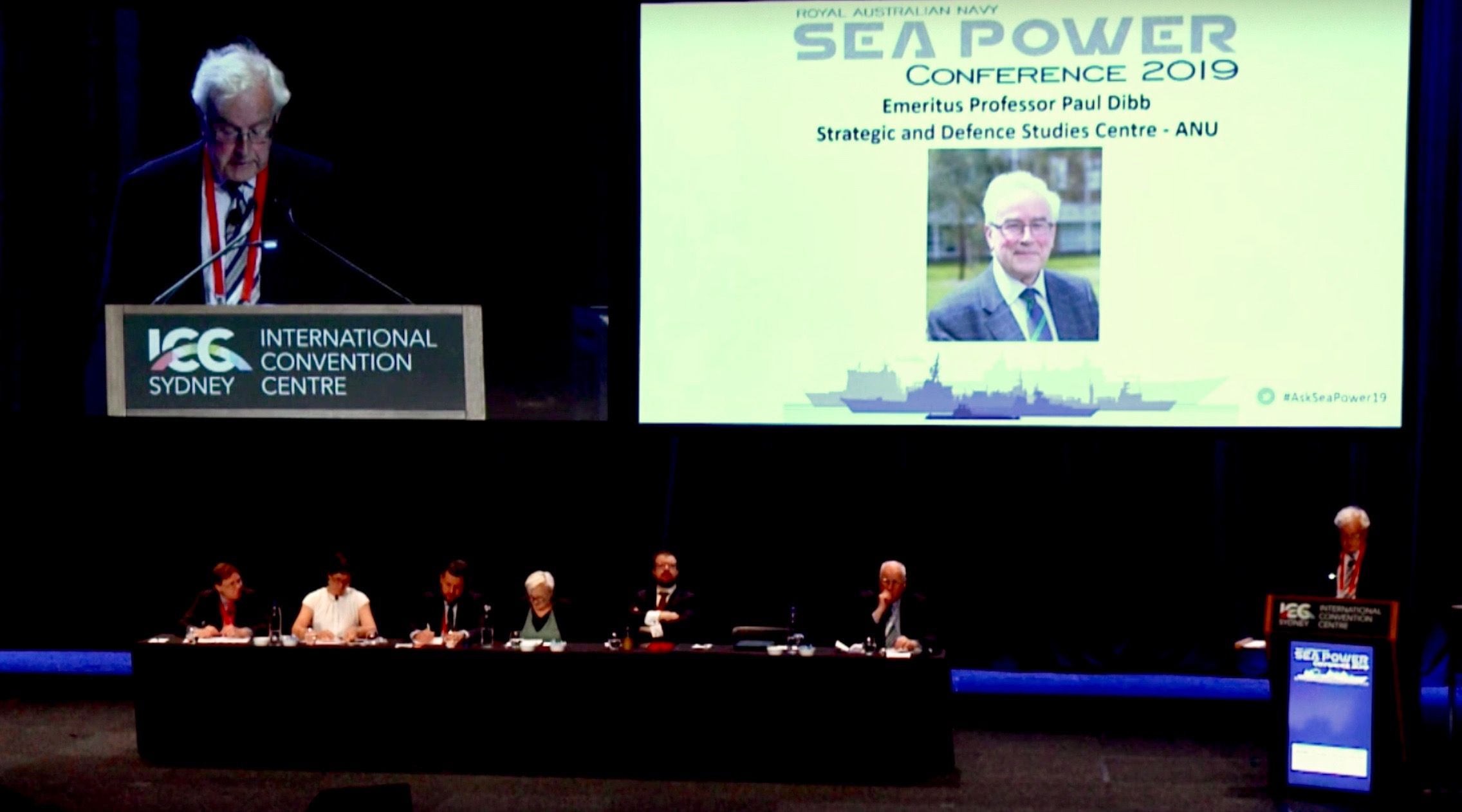

But during the most recent visit, I was able to attend a session of the Chief of Navy’s seapower conference and to listen to a panel in which Dibb participated which discussed the way ahead over the next five years in the Indo-Pacific region.

I have highlighted his presentation and the panel in an earlier piece.

But towards the end of my stay this October, I had the chance to sit down with Paul Dibb and to discuss further his thinking.

That interview follows:

Question: How would you characterize where you think Australia is at this current situation with regard to the competition with 21st century authoritarian powers?

Paul Dibb: My view is that we’re sleepwalking. Until recently, we’ve always had the view that there are no military powers in Australia’s region of primary strategic interest capable of invading us without a very significant period of warning time.

But that clearly has changed now. Many countries in our region, but especially China, are developing long range power projection that can reach Australia.

And with China’s militarization of bases in the South China Sea, China’s power projection capability is 1,400 kilometers closer to the North of Australia.

We’re now facing very short warning times when it comes to military capabilities which directly threaten our territory for the first time since the Second World War, because that’s what China has built up and the trajectory they are on.

As you know from your time in Australia, the strategic community is now discussing this challenge and how to wrestle with the problems posed by the new strategic situation.

But our politicians are not terribly interested because they’re thinking about the here and now, the everyday problems of running a government with a Parliamentary majority in this case of one. And the bureaucracy also seems to be still using a short- time horizon.

But we now need to study in detail what the intelligence warning indicators are and how are we going to deal with China as a potential adversary.

Question: What then are the questions which need to be addressed and answered by the Australian government in the new strategic situation?

Paul Dibb: The key building blocks are for the National Security Committee of Cabinet in closed session to discuss these issues, and it can be secret as far as I’m concerned, to recognize that we now face a potential major threat.

And it is not just the question of China or Russia. Should the democratic experiment in Indonesia fail and should we have in the contingent future an Indonesia with 300 million people that is extreme Islamic and military in its persuasion, you can forget us focusing on anything else but Indonesia. It’s only one hour’s civil airline flying time from Darwin to the nearest Indonesian territory.

What worries me is that we’ve had deep in our psyche that we have a large continent difficult to invade. Our distance and depth provide us with a natural basis for defense.

But the actual state of our ability to leverage our geography is not good.

For example, the operational military bases for air force and navy in the North and the West, certainly in the North, have been run down. They’re vulnerable, they need hardening, their fuel supplies are at risk. They need protection, and that’s going to cost money, and that means, to answer your question, we need to be getting the government to look at mobilization. We haven’t done that since the infamous days in the 1950s and 1960s of The War Book.

And with regard to China, it is not just a question of military power narrowly considered. We need to understand that China is challenging our strategic space in the South China Sea and South East Asia and the South Pacific, and we need to be alert to how much more is China and Russia going to do together in this part of the world.

The the central issue is shaping modern mobilization capabilities and increased self-reliance. It does not and never will mean for a country of this size of population or industry to have self-sufficiency, but now the potential adversary is knocking on the door for the first time since the second world war, and yet we’re sauntering along in this sleepwalking attitude that, to use an Australian expression, she’ll be right. Everything will be okay. We’re not even planning for the contingency, what if it is not okay.

Question: In the Williams Seminars and in my discussions in Australia over the past few years, there is clearly much more concern about finding ways to shape a more resilient Australia and to enhance the industrial capabilities to sustain the ADF in times of crisis.

What is your perspective on this aspect of the response in Australia to the new strategic situation?

Paul Dibb: New thinking is clearly demanded as we reshape our approach to defense strategy. That demands new approaches to our defence policy formulation.

For example, at the recent Chief of Navy’s Sea Power Conference, I attended the closing session where the Secretary of Defense, Secretary of Foreign Affairs, and Secretary of Finance presented and they emphasized how they coordinate with each other. In my time as Deputy Secretary of Defense, we were fairly stove piped and didn’t relate much to the rest of government in Canberra.

But although they’re talking more to each other, the sorts of things you’re raising about water, or fuel supply, are clearly not priorities. And the question of the kind of defense industrial support we will need, such as software code rewriting of our core systems in a crisis to gain transient advantage is not yet a priority. We’ve got an educated country but mobilization of such a capability as software code rewriting done in a crisis does not yet seem to be a priority.

No matter how close our access is to fifth generation systems if we’re in a regional contingency and you’re a bit busy somewhere else, we need the capacity to alter the source code ourselves and adapt it for new operational conditions.

And clearly, what analysts are referring to as the challenges in the gray zone are in the domain we are talking about.

Our Chief of Defense Force, General Angus Campbell, gave a speech in June at ASPI and highlighted the challenges and dangers with regard to gray zone activities, which is to say using coercion, disruption and supply chain denial to get what they want, rather than having to start and end with kinetic force.

The Chinese have clearly expanded into the South China Sea, but critical to Australia is whether the South Pacific is next.

It is very likely China wants to squeeze our strategic space not just in Southeast Asia but the South Pacific

This demands different thinking in Canberra, and it demands bringing together the things you’ve raised, like fuel supplies, like water, like source code writing, like mobilization.

It is about not allowing a gray zone to exist dominated by the 21st century authoritarian powers.

The featured photo shows Paul Dibb at Maritime Conference October 2019.

1906-CDF-ASPI-SPEECH-for-publication-1