The United States and Indo-Pacific Defense Operations: Adding Prompt Strike to the “Fight Tonight Force”

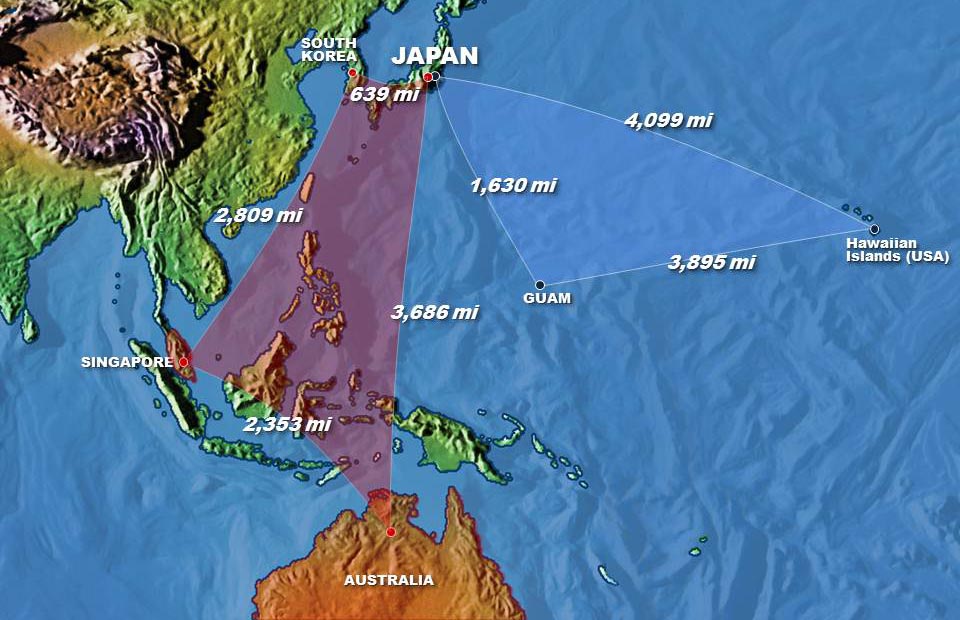

When we published our 2013 book on Indo-Pacific defense, entitled Rebuilding American Military Power in the Pacific: A 21st-Century Strategy, we highlighted the strategic geometry facing the challenge of operating U.S. forces in the Pacific.

We highlighted the challenge by crafting the graphic above.

The U.S. faces a tyranny of distance in dealing with the Pacific. As one Admiral put it to me: “In effect, the Indo-Pacific sea space is the equivalent of three Atlantic Oceans.”

Projecting from the United States, American forces need to generate force from the United States and then from a strategic triangle going from Hawaii to Guam and to Japan. And then the American forces need to project force into in a strategic quadrangle which reaches from Japan to South Korea, to Singapore and to Australia.

Since 2013, the United States has worked a deepening relationship with the Philippines and Australia in terms of shaping additional paths from which to project force, and the Australian Defence Force (ADF) is itself engaged in ways to extend its reach into the Pacific. I have written four books on Australian defence which highlight the Australian transition and its relationship to what other allies are doing in the region.

We emphasized in the book, the key necessity to enhance the sensor and interactive reach of a distributed force. Over the past decade, the U.S. military has been engaged in a significant force distribution effort. The U.S. Navy has pursued distributed maritime operations, the USAF has pursued agile combat employment, and the USMC is pursuing various force distribution efforts, notably Distributed Aviation Operations and Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations.

In my book on the paradigm shift in maritime operations, I add an additional concept capturing a way ahead, namely distributed maritime effects. By using aircraft, and air and maritime systems, the American and allied forces will be able to distribute military power without needing traditional air basing or over-reliance on capital ships to affect the battlespace.

Such a distribution of military force packages or “combat clusters” has been done in order to enhance the survivability of our forces against an adversary’s forces, but such dispersion comes at a cost in terms of the investment that needs to be made in how to sustain and reinforce such a force with the weapons and fuel that it needs to empower such a force.

A key advantage of such a force is that over the vast distances of the Pacific by working more effective relationships with allies, a distributed American force can build a lego-block like blanket force over the extended battlespace. It can allow a distributed force to have more effective presence and engagement with allies which makes it much more difficult for the Chinese, the Russians or the North Koreans to be certain of their ability to destroy enough American capability to ensure their own mission success.

Such an approach is precisely designed to convince the adversary that a rapid victory is not on the table and the extent to which the American forces are embedded in a web of allied capabilities where there are shared interests and values resisting the projection of power from the multi-polar authoritarian world, war can be deterred as well.

Now let me return to the testimony of the Indo-PACOM commander, Admiral Paparo and consider how such an approach would be executed. Paparo’s testimony is very rich and indeed complicated, and I first addressed his April Congressional testimony in an article entitled: The U.S. Approach to Defense and Deterrence in the Indo-Pacific: Deconstructing Admiral Paparo’s Recent Testimony.

Here I am simply going to focus on the distributed force and enhancing the capabilities of the “fight tonight force” to enhance the capabilities of such a force.

In his testimony, the Admiral highlighted a number of ways by which the “fight tonight distributed force” can be realistically enhanced.

Among the priorities are the following:

- Enhanced C5ISRT systems: He emphasizes the need for superior information systems with AI and machine learning capabilities that can function in contested environments, reducing planning time from days to hours and providing comprehensive battlespace awareness.

- Advanced autonomous systems: The Admiral highlights AI-enabled autonomous systems (uncrewed surface vehicles, autonomous aerial systems, undersea vehicles) as providing “significant and affordable asymmetric advantage” against numerically superior opponents with legacy technology.

- Distributed posture initiatives: He advocates for expanding the number of operating locations across the region to complicate adversary planning, including using the Joint Posture Management Office to streamline construction projects in places like the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Palau, and Micronesia.

- Robust logistics networks: The Admiral emphasizes developing Joint Theater Distribution Centers as critical logistics nodes, increasing assured fuel access points (18 added in the past year), and hardening existing facilities against missile and cyber attacks.

- Strengthened alliances: The Admiral repeatedly emphasizes that America’s network of allies and partners is “a tremendous asymmetric advantage” that no competitor can match, focusing on multilateral activities like joint exercises (120 in total) to improve interoperability.

I have argued that the American defense posture shift to deploying an integrated but distributed force structure is a strategic one. And have not only argued since 1991 in both my writings and my work that only by embedding such a strategic shift within a network of allies and partners that take their defense seriously can we deal effectively with the rise of what I have called the multi-polar authoritarian world.

Admiral Paparo views distributed American forces and allied relationships as mutually reinforcing elements of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s (USINDOPACOM) strategy.

In his testimony he indicates that:

- Allied relationships provide geographic advantages that support the distribution of American forces. As stated on page 10, “The U.S. network of allies and partners represents a tremendous asymmetric advantage in the Indo-Pacific” that provides “geographic advantages” which help secure “access, basing, and overflight” for U.S. forces.

- Distributed forces strengthen allied partnerships. The document notes that forces positioned west of the international dateline “conduct theater security cooperation to improve the capacity of U.S. allies and partners, increase interoperability, and demonstrate to adversaries that conflict includes the prospect of coalition operations” (page 8).

- Agile posture and access agreements with allies are essential for effective distributed operations. The document emphasizes that “Securing access, basing, and overflight (ABO) with the right forces at the right times ensures a mobile and distributed force disposition” (page 17).

- Multilateral exercises are used to validate and improve distributed force concepts. For example, Exercise Valiant Shield is described as building “real-world proficiency in detecting, locating, tracking, and engaging units at sea, in the air, in space, on land, and in cyberspace” (page 6).

Admiral Paparo clearly sees the network of allies and partners as enabling the distributed force posture necessary to deter China, while the visible presence of distributed U.S. forces reciprocally strengthens those alliances by demonstrating U.S. commitment to regional security.

While force distributed interconnected with enhanced allied defense capabilities, whether enhancing their capabilities of being porcupines or of contributing to collective longer-range reach, is foundational, such an approach only enhances the need for speed in terms of having longer range conventional capabilities that can reach out and touch the adversary’s initial projection force and affect their decision cycle.

In my view, the combination of an enhanced embedded distributed force with prompt strike delivered by bombers and high-speed missiles becomes the urgent deployment priority to work seamlessly with a deterrence or war winning approach.

Distributed deployment provides for enhanced survivability and interlocking presence capability to place a strong defensive grid over the areas of interest.

What it does not do in and of itself is to deliver the prompt strike which would disrupt the adversary’s initial projection of power. That is where in my view deploying the B-21 bomber and the early deployment of hypersonic missiles comes into play.

In his testimony Admiral Paparo underscores the importance of “persistent mass of fires” through both upgrading existing systems and transitioning to advanced platforms like Virginia-class submarines with payload modules and B-21 Raider aircraft.

He has highlighted the importance as well of the hypersonic threat from China and Russia. But of course, a distributed force attenuates using these capabilities effectively but if your own distributed forces have access to such weapons, the threat envelope to the adversary increases dramatically.

Admiral Paparo has emphasized their strategic importance, stating he “favors speeding up the fielding of U.S. hypersonic missiles” for both the Army and Navy. He explained that these systems are needed to “close in time any actor’s kill chain,” warning that “If your adversary can strike you five times faster than you can strike your enemy, it incentivizes first strikes.” He emphasized that “The coin of the realm in the 21st century is speed. Who does things faster wins.”

He specifically mentioned that “fielding U.S. hypersonic missiles is critical to countering the asymmetry of Chinese hypersonic missiles.”

Combining an ability to “fight at the speed of light” with a distributed force embedded in a grid of partner and allied defense efforts will significantly enhance the capabilities of the “fight tonight force” in the Indo-Pacific.

See also the following: