Interactivity, Platforms, and Shaping a Way Ahead

This is the fourth article in a series on the USMC Aviation and its work in progress on digital interoperability.

In this article, I am focusing on what enhanced platform incorporation into expanded networks may mean in terms of enhanced MAGTF capabilities and contributions.

What do enhanced network engagement capabilities bring to core USMC aviation platforms, and how does such efforts expand USMC capabilities and their contribution to the USN-USMC team?

My discussions with Major Salvador Jauregui and Mr. Lowell Schweickart from the USMC Aviation Headquarters who are working on the digital interoperability effort were a key input to this article, but I am going to provide some key takeaways from my discussions with them which highlight the interactivity between platforms and digital interoperability and how opening the network aperture can drive change.

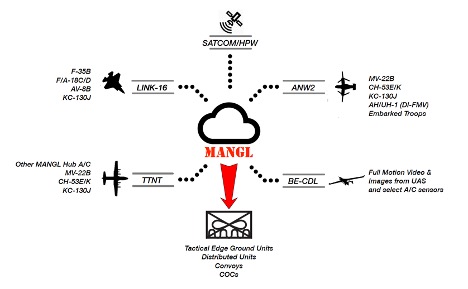

Let us start by returning to the core MANGL diagram which was included in the second article.

In that article, we focused on the networks being worked in across the USMC aviation to work greater connectivity and integrability.

In this piece, I am going to focus on two of the platforms, the Viper attack helicopter and the CH53E/K and highlight what is being added to each one and with what potential consequences for the enhanced capabilities of those platforms and their potential contribution to the MAGTF.

The digital interoperability team highlighted that in their view C2 was a weapon system and needed to be regarded as such. And they say the DI efforts as augmenting Marines perception of the importance of C2 and its role within the evolution of the force.

The team highlighted a core example of how the approach was reshaping capabilities.

“We have approximately 10,000 AN/PRC-117G radios in the inventory. This is a man-portable, tactical software-defined combat-net radio. It does advanced networking wave form, ANW2.

“To date if you wanted to give the Ground Combat Element (GCE) access to Link 16 data, they would have to be given Link-16 terminals. With the ANW2 connectivity on Marine Corps Aviation we can now provide access to Link-16 data to the GCE. By having access to a MAGTAB and a ANW2 enabled radio. We can provide the GCE with the Link 16 picture, with the information that they need.”

With regard to BE-CDL, this is a DOD-wide mandated wave form for working with unmanned full motion video data transfers. With the growing impact of full motion video, where one can envisage such data becoming ubiquitous on the battlefield, clearly ensuring that USMC aviation assets can work with this wave form in their support of the GCE is crucial.

Tactical Targeting Network Technique or TTNT is a US Navy wave form. This allows for integration with the US Navy but it also was a launch point when the DI project was started.

“TTNT was one of a few wave forms that existed that we could link, daisy chain data together and move data from one end to the other across multiple nodes without losing significant amounts of data.”

What is the overall objective of the DI effort?

“We are working to provide the Marines with common tactical picture. Regardless of where you plug in the combat cloud, you have a common picture. That allows me to collaborate and have the same point of reference as my counterpart who is plugged into a different injection point on that cloud.”

They added: “If we expect to use C2 as a weapon system in the future, we will need to up our game. We will need to become proficient in C2 in a way we have not been.”

The Viper Case

To provide one example of how the change is envisaged, one could take the case of the USMC attack helicopter, the Viper. The USMC/NAVY team is planning to install a miniaturized mesh network manager which can be set in the size constraints within the platform. This will be coupled with a small form factor link transceiver which will give them access to Link 16 and ANW2.

Additionally, the equipment will be supplemented with a BE-CDL capable transceiver, providing the ability to exchange full motion video.

These capabilities will be coupled with a MAGTAB in the cockpit. The MAGTAB end user interface will serve as a system interface, a planning / briefing /debriefing tool and will serve as the cockpit electronic knee board.

What then might this mean for the future role of the Viper in the combat force?

In my view (and not attributing this to the DI team), this can lead to a significant change in how the Viper can operate on the battlefield in support of the GCE and highlight a new role in its at sea role, namely, to contribute to sea control.

With the upgrades coming soon via the digital interoperability initiative, the Viper through its Link 16 upgrade along with its Full-Motion video connectivity upgrade, can have access to a much wider situational awareness capability which obviously enhances both its organic targeting capability and its ability to work with a larger swath of integrated combat space.

This means that the Viper can broaden its ability to support other air platforms for an air-to-air mission set, or the ground combat commander, or in the maritime space.

A key capability which the Viper has is its high-powered machine gun. Given that the Viper can easily land on virtually any ship which the Navy or MSC operates, it can bring its machine gun as well as its Hellfire missiles, or its rockets with a laser seeker into the sea control domain

The increasing threat from small boats and unmanned air vehicles or the coming threat from unmanned surface vessels highlights the importance of having a platform which can use a variety of strike capabilities to destroy these relatively low value assets with potentially a high impact on the fleet. Unmanned assets may look smart, but when running into a machine gun, they return to simply being drones.

The combination of what the organic asset can do with its expanded span of SA and shared targeting information through the DI upgrades provides a new role for the Viper within the maritime force. This role is inherent within its current configuration coupled with the DI upgrades.

The CH-53E to CH-53K and the DI Impact

Another example which highlights the approach is the transition from the CH-53E to the CH-53K.

With the CH-53E and the initial CH-53K aircraft, they are adding similar systems to deliver enhanced connectivity.

The legacy CH-53E, which is approaching its sundown will address DI in reduced fashion, targeting Link 16 and ANW2 for insertion into the heavy lift helicopter.

This will allow the legacy asset, the CH-53E to better connected into its ground support missions, and maintain an awareness and presence within the air C2 picture.

But the CH-53K is an all-digital aircraft with advanced avionics onboard the aircraft. These capabilities expand what the CH-53K can provide for a support or assault mission.

As I argued in a May 22, 2019 piece on the CH-53K:

One of those (new) capabilities is the new cockpit in the aircraft and how digital interoperability and integration with the evolution of the MAGTF more broadly is facilitated by the operation of a 21st century cockpit.

The cockpits are very different and fit in with a general trend for 21stcentury aircraft of having digital cockpits with combat flexibility management built in.

Because the flight crew is operating a digital aircraft, many of the functions which have to be done manually in the E, are done by the aircraft itself.

This allows the cockpit crew to focus on combat management and force insertion tasks.

And the systems within the cockpit allow for the crew to play this function.

This means that the K and its onboard Marines and cargo can be integrated into a digitally interoperable force.

This means as well that the K could provide a lead role for the insertion package, or provide for a variety of support roles beyond simply bringing Marines and cargo to the fight.

They are bringing information as well which can be distributed to the combat force in the area of interest.

As the CH-53K enters the fleet as an operational asset, the connectivity solution will be upgraded to allow for that solution set to tap into the information generated by the systems onboard the CH-53K and to then distribute that information to other blue side platforms in the battlespace.

But when a platform enters the force which is new and more capable such as the CH-53E to CH-53K transition, the approach needs to be able to leverage those new information generating capabilities for the force more generally.

In my discussion with the DI team, I drew upon my meeting with Colonel Perrin at Pax River to discuss the concept of Kilos flying with unmanned “Mules” to bring supplies in support of embarked Marines.

As Col. Perrin noted in our conversation: “The USMC has done many studies of distributed operations and throughout the analyses it is clear that heavy lift is an essential piece of the ability to do such operations.”

And not just any heavy lift – but heavy lift built around a digital architecture.

Clearly, the CH-53E being more than 30 years old is not built in such a manner; but the CH-53K is.

What this means is that the CH-53K “can operate and fight on the digital battlefield.”

And because the flight crew are enabled by the digital systems onboard, they can focus on the mission rather than focusing primarily on the mechanics of flying the aircraft. This will be crucial as the Marines shift to using unmanned systems more broadly than they do now.

For example, it is clearly a conceivable future that CH-53Ks would be flying a heavy lift operation with unmanned “mules” accompanying them. Such manned-unmanned teaming requires a lot of digital capability and bandwidth, a capability built into the CH-53K.

If one envisages the operational environment in distributed terms, this means that various types of sea bases, ranging from large deck carriers to various types of Maritime Sealift Command ships, along with expeditionary bases, or FARPs or FOBS, will need to be connected into a combined combat force.

To establish expeditionary bases, it is crucial to be able to set them up, operate and to leave such a base rapidly or in an expeditionary manner (sorry for the pun).

This will be virtually impossible to do without heavy lift, and vertical heavy lift, specifically.

Put in other terms, the new strategic environment requires new operating concepts; and in those operating concepts, the CH-53K provides significant requisite capabilities.

Their response to my Perrin discussion with regard to the coming of the CH-53K and its impact when DI is considered as well: “What you are suggesting is the creation and operation of a subnet. This makes a great deal of sense and is part of what we see emerging from our approach to DI.”

This is how the DI team put it in the discussion:

“When it comes time to field the mesh network manager on the KILO, there will be an opportunity to integrate all of the capabilities that we’ve developed iteratively along the way.

“And then in addition to that, there will be an opportunity through the avionics buses, pull information off the 53-KILO and then populate it onto a network.”

Conclusion

Going forward, there are clearly technology solutions to how to manage size constraints which could provide the Marines with options to build beyond currently prosecuted solution sets.

In the MANGL approach, there are hubs which can work the most complete translation and management effort, versus smaller sized nodes on platforms which are users, receivers or transmit points. These “smaller sized nodes” can create connections with other “smaller sized nodes” via a single waveform. In effect, we are talking about hubs and spokes within the overall MANGL approach.

In effect what is being underscored is the challenge of integrating the disparate networks and C2 systems to get a more effective integrated force. After all, C2 is a core weapon system, and my view crafting a full spectrum crisis management force able to make decisions at the tactical edge is the 6th generation force.

For the earlier articles in the series:

The USMC and Digital Interoperability: Shaping an Integrated Distributed Force