Recollections on the Establishment of MAWTS-1

Trying to describe how MAWTS-1 and the WTI training concept began is very much like the classic tale of the blind men describing an elephant. After Vietnam, there were lots of Marines who were thinking about ways to improve Marine Corps Aviation and there were many initiatives throughout the Marine Corps. Everyone who participated in the establishment of MAWTS-1 and the development of the Weapons and Tactics (WTI) concept has a slightly different story.

This article presents my recollections.

In 1976 I was stationed at NAS Miramar, scheduled to be the Executive Officer of the first Marine Corps F-14 Squadron. When the Marine Corps decided the F-14 was the wrong fighter for the Marine Corps and canceled its participation, Colonel Bob Norton, Commanding Officer of MCCRTG-10, asked me to come to MCCRTG-10 in Yuma, Arizona. After closing down the Marine Command at MCAS Miramar, I transferred to MCAS Yuma with several of the Pilots and Radar Intercept Officers who had been part of the F-14 Program and a few of us went to work on building an F-4 Training Program using the Instructional Systems Development (ISD) construct that was used to develop the F-14 Classroom Training System.

Captains Rick Scivicque, Rob Savio, Jim Hollopeter, Jerry Cross and I put together an F-4 ISD based training system with funding from Jim Bolwerk, a retired Naval Aviator, who was heading up the Navy’s Training Directorate at COMNAVAIRPAC. The funding went through the Aviation Training Department at Headquarters Marine Corps and was supported by Colonel Paul Boozman. Colonel Boozman would have preferred development of a Helicopter Training Program, but the money was controlled by COMNAVAIRPAC and was earmarked for Navy and Marine Corps F-4 use.

Colonel Boozman knew that Marine Corps helicopter training was in need of a more standardized, focused, and formal program that would teach the tactics and skills necessary for force projection in combat. I emphasize this point because his strong position on the need for improved tactical training for the Helicopter community helped ensure the inclusion of helicopter training and, broadly, inclusion of training for all aviation assets in the development of the MAWTS/WTI concept.

While working on the F-4 ISD project Colonel Norton and his XO Colonel John Hudson made us aware of Project 19, one of the many recommendations on ways to improve Marine Corps Combat Readiness that then Colonel John Cox presented to the Commandant. Colonel Norton directed us to put together a concept of how Marine Corps Aviation training could be improved.

Over the next year, working with people like Bill Bauer (CO of VMFAT-101), Bobby Butcher (XO and then CO of VMAT-201), Dave Vest (XO then CO of VMFA-531 and previous head of the F-4 shop in MAWTU-PAC), we put together our ideas and developed the MAWTS/WTI concept.

Collectively, we had not been satisfied with the application of air power in Vietnam, our only war experience. There were numerous tactical applications that were effective (A-6 strikes in the north; close air support; helicopter troop insert, withdrawal, and rescue; C-130 tactical resupply; and breaking the siege of Khe San are examples).

However, an overall strategy, the integration of aviation resources, and effective coordination with the ground elements was less than ideal. It was clear we lost more Marines than we should have because we were not well coordinated with the Ground Forces and weren’t well coordinated with other squadrons, especially with other types of fixed wing, helicopter, and transport aircraft squadrons.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Fleet Squadron training depended on the quality of the more experienced pilots and whether they would teach what they knew or just try to beat you and hope you would learn. The Special Weapons Training Units and later MAWTUPAC and MAWTULANT had good Attack and Fighter training and certification programs that helped the A-6, A-4 and F-4 communities standardize and improve their training and combat capability, but these were generally specific to the aircraft type and didn’t integrate the full range of aviation types and capabilities. The Navy’s “Top Gun” school that started in the 1970’s was excellent for the improvement of individual Air Combat Maneuvering (ACM) skills but was available only to F-4 fighter crews.

Integrated training with the Marine Corps Ground Forces was also less than optimum. While there were opportunities to participate in some Ground Training Scenarios, the lack of participation in planning and debriefing led to exercises that failed to build the kind of integrated support that is necessary to be highly effective in combat.

We developed a concept that would include all aviation assets, working together as a coordinated and integrated team, to support a Ground Scheme of Maneuver. We fully understood that the value of the Marine Corps was invested in the troops on the ground who could defeat the enemy and take and occupy the terrain that is critical for winning battles and wars and knew it was our job to provide the best possible air support to enhance their combat capability.

While we were working on the concept at MCAS Yuma and El Toro, California, there were other Marines throughout the Corps who were developing similar and alternative concepts. It was clear the Marine Corps was going to do something significant to improve the training and application of our aviation assets. It remained to know where, what, and when.

Key elements of our concept were:

- The inclusion and integration of all Marine Corps aviation assets, every type of tactical aircraft, command and control, logistics, and air defense.

- Each year, train one pilot/aircrew from each squadron in the Marine Corps as Weapons and Tactics Instructors (WTIs) who would act as instructors and operations coordinators in their squadrons. Assign those pilots/aircrew back to their squadron for three, or at least a minimum of two years so that, once established, every squadron would have two WTI pilots/aircrews.

- Provide ground training on individual aircraft and the broad range of Marine Corps aviation assets to learn how to integrate and utilize the capabilities 0f the full range of Marine Aviation to support the Marine Corps Ground forces.

- Provide individual and combined-force flight training utilizing the best-known tactics for air combat and defensive combat maneuvering, ground attack, close air support, troop insertion, logistics supply, electronic warfare, command-and-control, and reconnaissance.

- Provide instruction on the capabilities of our known and potential enemies and the best tactics to defeat them.

Some senior officers thought the Command of MAWTS should be restricted to Fighter Pilots. We thought it important to share command of MAWTS among the communities to ensure broad buy-in of the concept, and recommended that the Commanding Officer shift from fixed wing to helicopter aviators every other change of command.

We also recommended that the incoming Commanding Officer should serve one year as Executive Officer to ensure a smooth transition from Commanding Officer to Commanding Officer, like the “Fleet-up” construct used in Navy Squadrons.

We didn’t alternate Command immediately because we had not brought a Helicopter pilot in as Executive Officer and thought it important that the next Commanding Officer be someone who was thoroughly familiar with the background and goals of MAWTS/WTI.

I recommended that Bobby Butcher be my relief because he was a proven leader, had helped develop the concept, fully understood what we were trying to do, had a successful Squadron Command, and could easily take over and maintain the momentum we had established.

Colonel Butcher cemented the practice of rotating the Command between fixed and rotary wing aviators and the Fleet-up construct by selecting Jake Vermilyea, a transport and helicopter pilot as his Executive Officer and eventual replacement as the third Commanding Officer of MAWTS-1. Colonel Butcher did this even though there was significant push-back from some Senior Fighter Pilots. It helped that LtGen White, a Helicopter pilot, was the Deputy Commandant for Aviation and supported Colonel Butcher’s position.

It is an understatement to say that not all Marine Aviators supported the MAWTS/WTI concept. Many thought it was far too expensive. There was significant push back on the inclusion of helicopters and transports based on the fear that the current MAWTU programs supporting A-6, A-4, and F-4 training would be watered down. There also was concern about Yuma as the location. Notably, Colonel John Ditto, Legislative Assistant to the Commandant, who had been the head of the F-4 Fighter Shop in MAWTULANT and was familiar with the ranges on the east coast, thought the new unit should be stationed out of Beaufort or Cherry Point.

The concept we put together in Yuma was pitched at a conference held at El Toro, chaired by Colonel Don Gillam of FMFPAC. Although some of the conference attendees did not fully support the concept as presented, Colonel Gillam deemed the conference enough of a success that he sent LtGen Andy O’Donnel, Commanding General FMFPAC, a message that FMFPAC should support the concept.

As a result of LtGen O’Donnel’s support, LtGen Tom Miller, Deputy Commandant for Aviation, asked for a briefing. LtCol Bill Cooper who was at HQMC AAP, presented the brief that we had developed and LtGen Miller approved the concept.

Concurrently, at Headquarters Marine Corps, a great deal of thought and planning had gone into the development of improved Aviation Training. Parallel with the development of our MAWTS/WTI concept, there was an initiative to merge the two MAWTUs.

The HQMC initiative and the MAWTS/WTI concept fit well together. A decision was made to have the new unit report to Aviation Training, where Colonel Paul Boozman was influential. His vision, direction, and support were important in forming MAWTS-1, from gaining support from the Commandant, providing the funding, approving the manning, and choosing the location.

It was decided to conduct a trial course under the direction of the MAWTUs. MAWTUPAC under LtCol Ray Hanle was selected to lead the effort. Instructors from the two MAWTUs, augmented by other highly respected pilots and crew members presented the first Weapons and Tactics Instructor (WTI) course in 1977. The course was enough of a success that a second trial class was conducted in early 1978. The success of those two WTI classes led to establishment and Commissioning of Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron-One (MAWTS-1) in June of 1978 with 35 officers and 19 enlisted Marines.

In researching this article, I have been reminded that there was a trial course held by MAWTULANT on the East Coast. That course apparently was not as well received as those held at Yuma, which helped cement the decision for Yuma as the best location.

A great deal of credit for the successful initiation of the MAWTS/WTI concept lies with Colonel Hanle and the MAWTU instructors who conducted those two first trial courses.

Much of the early success of MAWTS-1 came from the steady support of Colonel Boozman at Headquarters Marine Corps Aviation Training, and from LtCol Duane Wills in the Officer Assignment Branch. Colonel Boozman was instrumental in shaping the concept, and supporting and approving the training and command constructs, ensuring MAWTS-1 was fully staffed, and that it was adequately funded.

During my two years with MAWTS-1 we conducted four WTI Courses. Support from the Air Wings was excellent, and support from VMAT-102 and VMFAT-101 was outstanding, providing maintenance support and even aircraft when required.

There are some interesting stories about those first two years, such as the MAWTS-1 CH-53 Instructors being pulled out to support the training for the Iranian Hostage Rescue, a trip to Israel to confer with the leaders of the Entebbe Rescue, a Final Exercise evolution that was conducted in marginal weather, and the unfortunate loss of a CH-46 with Crew and passengers and loss of an F-4 Crew.

Near the end of my tenure, General Wilson, Commandant of the Marine Corps, visited the command for a briefing. In that brief I raised some issues of concern about the mobility of Command and Control, lack of armament for helicopters, and paucity of anti-air capability. While this was not the brief General Wilson had expected, it led to MAWTS being tied in with the Deputy for Aviation for discussion, participation, and influence on a variety of aviation issues.

I have had the pleasure of visiting MAWTS-1 several times since I retired in 1980. It appears that every Commanding Officer, with the support of the excellent MAWTS-1 Staff, has improved its value to the Marine Corps. The direct involvement of Secretary Lehman helped bring MAWTS-1 training to a higher level. MAWTS-1 has grown in size, mission depth, and overall capability.

We thought, when it first began, that Marine Corps Aviation would be improved and that someday most, if not all, Wing Commanders would be former MAWTS Instructors and/or WTIs which would certainly improve the coordination, integration, and combat capabilities of Marine Air. That has happened. The Marine Corps has even had a Commandant who was a MAWTS-1 Instructor.

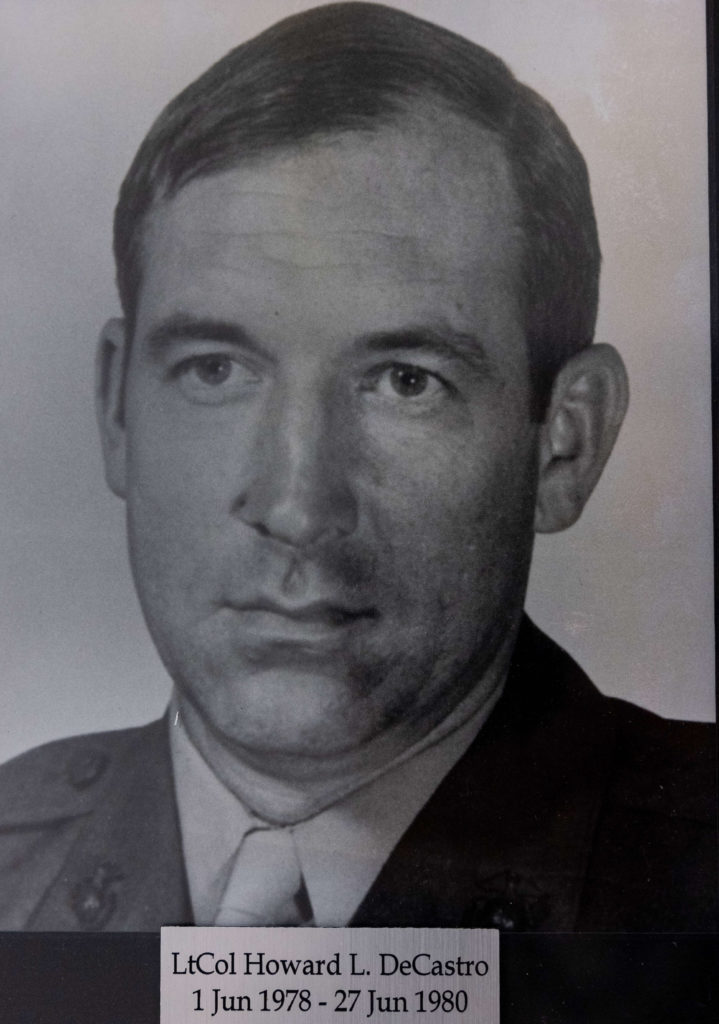

Featured Photo: The author was the first commander of MAWTS-1. The photo is from the wall on which all the commanders photos are to be found. Ed Timperlake and Robbin Laird are publishing a book on MAWTS-1 of which this article is part of that book.